Advice on Writing

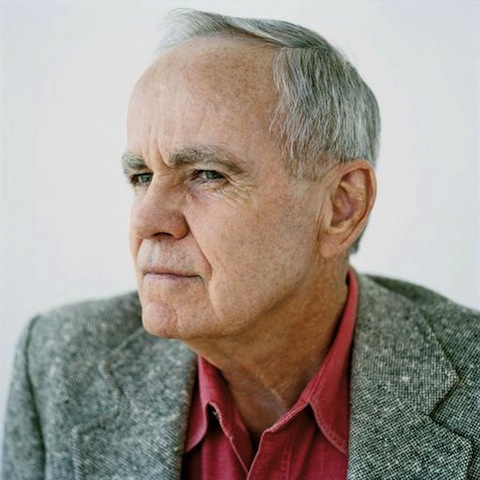

Cormac McCarthy has been—as one 1965 reviewer of his first novel, The Orchard Tree, dubbed him—a “disciple of William Faulkner.” He makes admirable use of Faulknerian traits in his prose, and I’d always assumed he inherited his punctuation style from Faulkner as well. But in his very rare 2008 televised interview with Oprah Winfrey, McCarthy cites two other antecedents: James Joyce and forgotten novelist MacKinlay Kantor, whose Andersonville won the Pulitzer Prize in 1955. Joyce’s influence dominates, and in discussion of punctuation, McCarthy stresses that his minimalist approach works in the interest of maximum clarity. Speaking of Joyce, he says,

James Joyce is a good model for punctuation. He keeps it to an absolute minimum. There’s no reason to blot the page up with weird little marks. I mean, if you write properly you shouldn’t have to punctuate.

So what “weird little marks” does McCarthy allow, or not, and why? Below is a brief summary of his stated rules for punctuation:

1. Quotation Marks:

McCarthy doesn’t use ‘em. In his Oprah interview, he says MacKinlay Kantor was the first writer he read who left them out. McCarthy stresses that this way of writing dialogue requires particular deliberation. Speaking of writers who have imitated him, he says, “You really have to be aware that there are no quotation marks, and write in such a way as to guide people as to who’s speaking.” Otherwise, confusion reigns.

2. Colons and semicolons:

Careful McCarthy reader Oprah says she “saw a colon once” in McCarthy’s prose, but she never encountered a semicolon. McCarthy confirms: “No semicolons.”

Of the colon, he says: “You can use a colon, if you’re getting ready to give a list of something that follows from what you just said. Like, these are the reasons.” This is a specific occasion that does not present itself often. The colon, one might say, genuflects to a very specific logical development, enumeration. McCarthy deems most other punctuation uses needless.

3. All other punctuation:

Aside from his restrictive rationing of the colon, McCarthy declares his stylistic convictions with simplicity: “I believe in periods, in capitals, in the occasional comma, and that’s it.” It’s a discipline he learned first in a college English class, where he worked to simplify 18th century essays for a textbook the professor was editing. Early modern English is notoriously cluttered with confounding punctuation, which did not become standardized until comparatively recently.

McCarthy, enamored of the prose style of the Neoclassical English writers but annoyed by their over-reliance on semicolons, remembers paring down an essay “by Swift or something” and hearing his professor say, “this is very good, this is exactly what’s needed.” Encouraged, he continued to simplify, working, he says to Oprah, “to make it easier, not to make it harder” to decipher his prose. For those who find McCarthy sometimes maddeningly opaque, this statement of intent may not help clarify things much. But lovers of his work may find renewed appreciation for his streamlined syntax.

James Joyce is a good model for punctuation. He keeps it to an absolute minimum. There’s no reason to blot the page up with weird little marks. I mean, if you write properly you shouldn’t have to punctuate.

So what “weird little marks” does McCarthy allow, or not, and why? Below is a brief summary of his stated rules for punctuation:

1. Quotation Marks:

McCarthy doesn’t use ‘em. In his Oprah interview, he says MacKinlay Kantor was the first writer he read who left them out. McCarthy stresses that this way of writing dialogue requires particular deliberation. Speaking of writers who have imitated him, he says, “You really have to be aware that there are no quotation marks, and write in such a way as to guide people as to who’s speaking.” Otherwise, confusion reigns.

2. Colons and semicolons:

Careful McCarthy reader Oprah says she “saw a colon once” in McCarthy’s prose, but she never encountered a semicolon. McCarthy confirms: “No semicolons.”

Of the colon, he says: “You can use a colon, if you’re getting ready to give a list of something that follows from what you just said. Like, these are the reasons.” This is a specific occasion that does not present itself often. The colon, one might say, genuflects to a very specific logical development, enumeration. McCarthy deems most other punctuation uses needless.

3. All other punctuation:

Aside from his restrictive rationing of the colon, McCarthy declares his stylistic convictions with simplicity: “I believe in periods, in capitals, in the occasional comma, and that’s it.” It’s a discipline he learned first in a college English class, where he worked to simplify 18th century essays for a textbook the professor was editing. Early modern English is notoriously cluttered with confounding punctuation, which did not become standardized until comparatively recently.

McCarthy, enamored of the prose style of the Neoclassical English writers but annoyed by their over-reliance on semicolons, remembers paring down an essay “by Swift or something” and hearing his professor say, “this is very good, this is exactly what’s needed.” Encouraged, he continued to simplify, working, he says to Oprah, “to make it easier, not to make it harder” to decipher his prose. For those who find McCarthy sometimes maddeningly opaque, this statement of intent may not help clarify things much. But lovers of his work may find renewed appreciation for his streamlined syntax.