Dear Xavier High School, and Ms. Lockwood, and Messrs Perin, McFeely, Batten, Maurer and Congiusta:

I thank you for your friendly letters. You sure know how to cheer up a really old geezer (84) in his sunset years. I don’t make public appearances any more because I now resemble nothing so much as an iguana.

What I had to say to you, moreover, would not take long, to wit: Practice any art, music, singing, dancing, acting, drawing, painting, sculpting, poetry, fiction, essays, reportage, no matter how well or badly, not to get money and fame, but to experience becoming, to find out what’s inside you, to make your soul grow.

Seriously! I mean starting right now, do art and do it for the rest of your lives. Draw a funny or nice picture of Ms. Lockwood, and give it to her. Dance home after school, and sing in the shower and on and on. Make a face in your mashed potatoes. Pretend you’re Count Dracula.

Here’s an assignment for tonight, and I hope Ms. Lockwood will flunk you if you don’t do it: Write a six line poem, about anything, but rhymed. No fair tennis without a net. Make it as good as you possibly can. But don’t tell anybody what you’re doing. Don’t show it or recite it to anybody, not even your girlfriend or parents or whatever, or Ms. Lockwood. OK?

Tear it up into teeny-weeny pieces, and discard them into widely separated trash recepticals [sic]. You will find that you have already been gloriously rewarded for your poem. You have experienced becoming, learned a lot more about what’s inside you, and you have made your soul grow.

God bless you all!

Kurt Vonnegut

I thank you for your friendly letters. You sure know how to cheer up a really old geezer (84) in his sunset years. I don’t make public appearances any more because I now resemble nothing so much as an iguana.

What I had to say to you, moreover, would not take long, to wit: Practice any art, music, singing, dancing, acting, drawing, painting, sculpting, poetry, fiction, essays, reportage, no matter how well or badly, not to get money and fame, but to experience becoming, to find out what’s inside you, to make your soul grow.

Seriously! I mean starting right now, do art and do it for the rest of your lives. Draw a funny or nice picture of Ms. Lockwood, and give it to her. Dance home after school, and sing in the shower and on and on. Make a face in your mashed potatoes. Pretend you’re Count Dracula.

Here’s an assignment for tonight, and I hope Ms. Lockwood will flunk you if you don’t do it: Write a six line poem, about anything, but rhymed. No fair tennis without a net. Make it as good as you possibly can. But don’t tell anybody what you’re doing. Don’t show it or recite it to anybody, not even your girlfriend or parents or whatever, or Ms. Lockwood. OK?

Tear it up into teeny-weeny pieces, and discard them into widely separated trash recepticals [sic]. You will find that you have already been gloriously rewarded for your poem. You have experienced becoming, learned a lot more about what’s inside you, and you have made your soul grow.

God bless you all!

Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut’s Eight Tips on How to Write a Good Short Story in Books, Literature, Writing | June 20th, 2012 9 Comments

When it came to giving advice to writers, Kurt Vonnegut was never dull. He once tried to warn people away from using semicolons by characterizing them as “transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing.” In this brief video, Vonnegut offers eight tips on how to write a short story:

When it came to giving advice to writers, Kurt Vonnegut was never dull. He once tried to warn people away from using semicolons by characterizing them as “transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing.” In this brief video, Vonnegut offers eight tips on how to write a short story:

- Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.

- Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for.

- Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

- Every sentence must do one of two things–reveal character or advance the action.

- Start as close to the end as possible.

- Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them–in order that the reader may see what they are made of.

- Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.

- Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To heck with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages.

From a January 26, 1947, contract between Kurt Vonnegut and his pregnant wife, Jane, to whom he had been married for sixteen months. Kurt Vonnegut: Letters, edited by Dan Wakefield, will be published next month by Delacorte Press.

I, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., that is, do hereby swear that I will be faithful to the commitments hereunder listed:

I. With the agreement that my wife will not nag, heckle, or otherwise disturb me on the subject, I promise to scrub the bathroom and kitchen floors once a week, on a day and hour of my own choosing. Not only that, but I will do a good and thorough job, and by that she means that I will get under the bathtub, behind the toilet, under the sink, under the icebox, into the corners; and I will pick up and put in some other location whatever movable objects happen to be on said floors at the time so as to get under them too, and not just around them. Furthermore, while I am undertaking these tasks I will refrain from indulging in such remarks as “Shit,” “Goddamn sonofabitch,” and similar vulgarities, as such language is nerve-wracking to have around the house when nothing more drastic is taking place than the facing of Necessity. If I do not live up to this agreement, my wife is to feel free to nag, heckle, and otherwise disturb me until I am driven to scrub the floors anyway--no matter how busy I am.

II. I furthermore swear that I will observe the following minor amenities:

a. I will hang up my clothes and put my shoes in the closet when I am not wearing them;

b. I will not track dirt into the house needlessly, by such means as not wiping my feet on the mat outside and wearing my bedroom slippers to take out the garbage;

c. I will throw such things as used-up match folders, empty cigarette packages, the piece of cardboard that comes in shirt collars, etc., into a wastebasket instead of leaving them around on chairs or the floor;

d. After shaving I will put my shaving equipment back in the medicine closet;

e. In case I should be the direct cause of a ring around the bathtub after taking a bath, I will, with the aid of Swift’s Cleanser and a brush, not my washcloth, remove said ring;

f. With the agreement that my wife collects the laundry, places it in a laundry bag, and leaves the laundry bag in plain sight in the hall, I will take said laundry to the Laundry not more than three days after said laundry has made its appearance in the hall; I will furthermore bring the laundry back from the Laundry within two weeks after I have taken it;

g. When smoking I will make every effort to keep the ashtray I am using at the time upon a surface that does not slant, sag, slope, dip, wrinkle, or give way upon the slightest provocation; such surfaces may be understood to include stacks of books precariously mounted on the edge of a chair, the arms of the chair that has arms, and my own knees;

h. I will not put out cigarettes upon the sides of, or throw ashes into, either the red leather wastebasket or the stamp wastebasket that my loving wife made me for Christmas, 1945, as such practice noticeably impairs the beauty and ultimate practicability of said wastebaskets;

i. In the event that my wife makes a request of me, and that request cannot be regarded as other than reasonable and wholly within the province of a man’s work (when his wife is pregnant, that is), I will comply with said request within three days after my wife has presented it. It is understood that my wife will make no reference to the subject, other than saying thank you, of course, within these three days; if, however, I fail to comply with said request after a more substantial length of time has elapsed, my wife shall be completely justified in nagging, heckling, or otherwise disturbing me until I am driven to do that which I should have done;

j. An exception to the above three-day time limit is the taking out of the garbage, which, as any fool knows, had better not wait that long; I will take out the garbage within three hours after the need for disposal has been pointed out to me by my wife. It would be nice, however, if, upon observing the need for disposal with my own two eyes, I should perform this particular task upon my own initiative, and thus not make it necessary for my wife to bring up a subject that is moderately distasteful to her;

k. It is understood that, should I find these commitments in any way unreasonable or too binding upon my freedom, I will take steps to amend them by counterproposals, constitutionally presented and politely discussed, instead of unlawfully terminating my obligations with a simple burst of obscenity, or something like that, and the subsequent persistent neglect of said obligations;

l. The terms of this contract are understood to be binding up until that time after the arrival of our child (to be specified by the doctor) when my wife will once again be in full possession of all her faculties, and able to undertake more arduous pursuits than are now advisable.

I, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., that is, do hereby swear that I will be faithful to the commitments hereunder listed:

I. With the agreement that my wife will not nag, heckle, or otherwise disturb me on the subject, I promise to scrub the bathroom and kitchen floors once a week, on a day and hour of my own choosing. Not only that, but I will do a good and thorough job, and by that she means that I will get under the bathtub, behind the toilet, under the sink, under the icebox, into the corners; and I will pick up and put in some other location whatever movable objects happen to be on said floors at the time so as to get under them too, and not just around them. Furthermore, while I am undertaking these tasks I will refrain from indulging in such remarks as “Shit,” “Goddamn sonofabitch,” and similar vulgarities, as such language is nerve-wracking to have around the house when nothing more drastic is taking place than the facing of Necessity. If I do not live up to this agreement, my wife is to feel free to nag, heckle, and otherwise disturb me until I am driven to scrub the floors anyway--no matter how busy I am.

II. I furthermore swear that I will observe the following minor amenities:

a. I will hang up my clothes and put my shoes in the closet when I am not wearing them;

b. I will not track dirt into the house needlessly, by such means as not wiping my feet on the mat outside and wearing my bedroom slippers to take out the garbage;

c. I will throw such things as used-up match folders, empty cigarette packages, the piece of cardboard that comes in shirt collars, etc., into a wastebasket instead of leaving them around on chairs or the floor;

d. After shaving I will put my shaving equipment back in the medicine closet;

e. In case I should be the direct cause of a ring around the bathtub after taking a bath, I will, with the aid of Swift’s Cleanser and a brush, not my washcloth, remove said ring;

f. With the agreement that my wife collects the laundry, places it in a laundry bag, and leaves the laundry bag in plain sight in the hall, I will take said laundry to the Laundry not more than three days after said laundry has made its appearance in the hall; I will furthermore bring the laundry back from the Laundry within two weeks after I have taken it;

g. When smoking I will make every effort to keep the ashtray I am using at the time upon a surface that does not slant, sag, slope, dip, wrinkle, or give way upon the slightest provocation; such surfaces may be understood to include stacks of books precariously mounted on the edge of a chair, the arms of the chair that has arms, and my own knees;

h. I will not put out cigarettes upon the sides of, or throw ashes into, either the red leather wastebasket or the stamp wastebasket that my loving wife made me for Christmas, 1945, as such practice noticeably impairs the beauty and ultimate practicability of said wastebaskets;

i. In the event that my wife makes a request of me, and that request cannot be regarded as other than reasonable and wholly within the province of a man’s work (when his wife is pregnant, that is), I will comply with said request within three days after my wife has presented it. It is understood that my wife will make no reference to the subject, other than saying thank you, of course, within these three days; if, however, I fail to comply with said request after a more substantial length of time has elapsed, my wife shall be completely justified in nagging, heckling, or otherwise disturbing me until I am driven to do that which I should have done;

j. An exception to the above three-day time limit is the taking out of the garbage, which, as any fool knows, had better not wait that long; I will take out the garbage within three hours after the need for disposal has been pointed out to me by my wife. It would be nice, however, if, upon observing the need for disposal with my own two eyes, I should perform this particular task upon my own initiative, and thus not make it necessary for my wife to bring up a subject that is moderately distasteful to her;

k. It is understood that, should I find these commitments in any way unreasonable or too binding upon my freedom, I will take steps to amend them by counterproposals, constitutionally presented and politely discussed, instead of unlawfully terminating my obligations with a simple burst of obscenity, or something like that, and the subsequent persistent neglect of said obligations;

l. The terms of this contract are understood to be binding up until that time after the arrival of our child (to be specified by the doctor) when my wife will once again be in full possession of all her faculties, and able to undertake more arduous pursuits than are now advisable.

On June 1, 1997, Mary Schmich, Chicago Tribune columnist and Brenda Starr cartoonist, wrote a column entitled “Advice, like youth, probably just wasted on the young.” In her introduction to the column she described it as the commencement speech she would give to the class of ’97 if she were asked to give one.

The first line of the speech: “Ladies and gentlemen of the class of ’97: Wear sunscreen.”

If you grew up in the 90s, these words may sound familiar, and you would be absolutely right. Australian film director Baz Luhrmann used the essay in its entirety on his 1998 album Something for Everybody, turning it into his hit single “Everybody’s Free (To Wear Sunscreen).” With spoken-word lyrics over a mellow backing track by Zambian dance music performer Rozalla, the song was an unexpected worldwide hit, reaching number 45 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the United States and number one in the United Kingdom.

The thing is, Luhrmann and his team did not realize that Schmich was the actual author of the speech until they sought out permission to use the lyrics. They believed it was written by author Kurt Vonnegut.

For Schmich, the “Sunscreen Controversy” was “just one of those stories that reminds you of the lawlessness of cyberspace.” While no one knows the originator of the urban legend, the story goes that Vonnegut’s wife, the photographer Jill Krementz, had received an e-mail in early August 1997 that purported to reprint a commencement speech Vonnegut had given at MIT that year. (The actual commencement speaker was the United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan.) “She was so pleased,” Mr. Vonnegut later told the New York Times. “She sent it on to a whole of people, including my kids – how clever I am.”

The purported speech became a viral sensation, bouncing around the world through e-mail. This is how Luhrmann discovered the text. He, along with Anton Monsted and Josh Abrahams, decided to use it for a remix he was working on but was doubtful he could get Vonnegut’s permission. While searching for the writer’s contact information, Luhrmann discovered that Schmich was the actual author. He reached out to her and, with her permission, recorded the song the next day.

What happened between June 1 and early August, no one knows. For Vonnegut, the controversy cemented his belief that the Internet was not worth trusting. “I don’t know what the point is except how gullible people are on the Internet.” For Schmich, she acknowledged that her column would probably not had spread the way it did without the names of Vonnegut and MIT attached to it.

In the end, Schmich and Vonnegut did connect after she reached out to him to inform him of the confusion. According to Vonnegut, “What I said to Mary Schmich on the telephone was that what she wrote was funny and wise and charming, so I would have been proud had the words been mine.” Not a bad ending for a column that was written, according to Schmich, “while high on coffee and M&Ms.”

The first line of the speech: “Ladies and gentlemen of the class of ’97: Wear sunscreen.”

If you grew up in the 90s, these words may sound familiar, and you would be absolutely right. Australian film director Baz Luhrmann used the essay in its entirety on his 1998 album Something for Everybody, turning it into his hit single “Everybody’s Free (To Wear Sunscreen).” With spoken-word lyrics over a mellow backing track by Zambian dance music performer Rozalla, the song was an unexpected worldwide hit, reaching number 45 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the United States and number one in the United Kingdom.

The thing is, Luhrmann and his team did not realize that Schmich was the actual author of the speech until they sought out permission to use the lyrics. They believed it was written by author Kurt Vonnegut.

For Schmich, the “Sunscreen Controversy” was “just one of those stories that reminds you of the lawlessness of cyberspace.” While no one knows the originator of the urban legend, the story goes that Vonnegut’s wife, the photographer Jill Krementz, had received an e-mail in early August 1997 that purported to reprint a commencement speech Vonnegut had given at MIT that year. (The actual commencement speaker was the United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan.) “She was so pleased,” Mr. Vonnegut later told the New York Times. “She sent it on to a whole of people, including my kids – how clever I am.”

The purported speech became a viral sensation, bouncing around the world through e-mail. This is how Luhrmann discovered the text. He, along with Anton Monsted and Josh Abrahams, decided to use it for a remix he was working on but was doubtful he could get Vonnegut’s permission. While searching for the writer’s contact information, Luhrmann discovered that Schmich was the actual author. He reached out to her and, with her permission, recorded the song the next day.

What happened between June 1 and early August, no one knows. For Vonnegut, the controversy cemented his belief that the Internet was not worth trusting. “I don’t know what the point is except how gullible people are on the Internet.” For Schmich, she acknowledged that her column would probably not had spread the way it did without the names of Vonnegut and MIT attached to it.

In the end, Schmich and Vonnegut did connect after she reached out to him to inform him of the confusion. According to Vonnegut, “What I said to Mary Schmich on the telephone was that what she wrote was funny and wise and charming, so I would have been proud had the words been mine.” Not a bad ending for a column that was written, according to Schmich, “while high on coffee and M&Ms.”

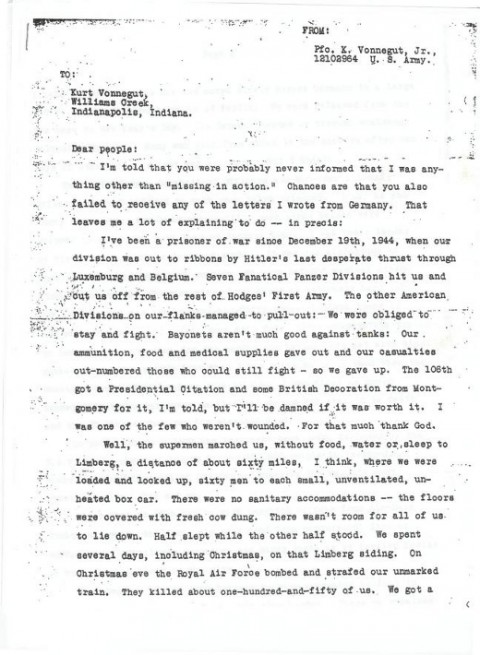

If you read Open Culture, smart money says you’ll also enjoy Letters of Note, a site we occasionally reference. They collect, post, and provide context for “fascinating letters, postcards, telegrams, faxes, and memos” to and from all manners of luminaries throughout the history of art, politics, music, science, media, and, er, letters. Dig into the archives and you’ll find a missive home from Kurt Vonnegut, a notable letter-writer if ever there was one. Dedicated Vonnegut readers will recognize the tone of the novelist, although here, at the age of 22, he had yet to become one. A Private in the Second World War, he was taken prisoner on December 19, 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge. Having then done time in an underground section of a Dresden work camp known, yes, as “Slaughterhouse Five,” he survived the subsequent bombing of the city and wound up in a repatriation camp by May 1945. There, he wrote what follows:

Dear people:

I’m told that you were probably never informed that I was anything other than “missing in action.” Chances are that you also failed to receive any of the letters I wrote from Germany. That leaves me a lot of explaining to do — in precis:

I’ve been a prisoner of war since December 19th, 1944, when our division was cut to ribbons by Hitler’s last desperate thrust through Luxemburg and Belgium. Seven Fanatical Panzer Divisions hit us and cut us off from the rest of Hodges’ First Army. The other American Divisions on our flanks managed to pull out: We were obliged to stay and fight. Bayonets aren’t much good against tanks: Our ammunition, food and medical supplies gave out and our casualties out-numbered those who could still fight – so we gave up. The 106th got a Presidential Citation and some British Decoration from Montgomery for it, I’m told, but I’ll be damned if it was worth it. I was one of the few who weren’t wounded. For that much thank God.

Well, the supermen marched us, without food, water or sleep to Limberg, a distance of about sixty miles, I think, where we were loaded and locked up, sixty men to each small, unventilated, unheated box car. There were no sanitary accommodations — the floors were covered with fresh cow dung. There wasn’t room for all of us to lie down. Half slept while the other half stood. We spent several days, including Christmas, on that Limberg siding. On Christmas eve the Royal Air Force bombed and strafed our unmarked train. They killed about one-hundred-and-fifty of us. We got a little water Christmas Day and moved slowly across Germany to a large P.O.W. Camp in Muhlburg, South of Berlin. We were released from the box cars on New Year’s Day. The Germans herded us through scalding delousing showers. Many men died from shock in the showers after ten days of starvation, thirst and exposure. But I didn’t.

Under the Geneva Convention, Officers and Non-commissioned Officers are not obliged to work when taken prisoner. I am, as you know, a Private. One-hundred-and-fifty such minor beings were shipped to a Dresden work camp on January 10th. I was their leader by virtue of the little German I spoke. It was our misfortune to have sadistic and fanatical guards. We were refused medical attention and clothing: We were given long hours at extremely hard labor. Our food ration was two-hundred-and-fifty grams of black bread and one pint of unseasoned potato soup each day. After desperately trying to improve our situation for two months and having been met with bland smiles I told the guards just what I was going to do to them when the Russians came. They beat me up a little. I was fired as group leader. Beatings were very small time: — one boy starved to death and the SS Troops shot two for stealing food.

On about February 14th the Americans came over, followed by the R.A.F. their combined labors killed 250,000 people in twenty-four hours and destroyed all of Dresden — possibly the world’s most beautiful city. But not me.

After that we were put to work carrying corpses from Air-Raid shelters; women, children, old men; dead from concussion, fire or suffocation. Civilians cursed us and threw rocks as we carried bodies to huge funeral pyres in the city.

When General Patton took Leipzig we were evacuated on foot to (‘the Saxony-Czechoslovakian border’?). There we remained until the war ended. Our guards deserted us. On that happy day the Russians were intent on mopping up isolated outlaw resistance in our sector. Their planes (P-39′s) strafed and bombed us, killing fourteen, but not me.

Eight of us stole a team and wagon. We traveled and looted our way through Sudetenland and Saxony for eight days, living like kings. The Russians are crazy about Americans. The Russians picked us up in Dresden. We rode from there to the American lines at Halle in Lend-Lease Ford trucks. We’ve since been flown to Le Havre.

I’m writing from a Red Cross Club in the Le Havre P.O.W. Repatriation Camp. I’m being wonderfully well feed and entertained. The state-bound ships are jammed, naturally, so I’ll have to be patient. I hope to be home in a month. Once home I’ll be given twenty-one days recuperation at Atterbury, about $600 back pay and — get this — sixty (60) days furlough.

I’ve too damned much to say, the rest will have to wait, I can’t receive mail here so don’t write.

May 29, 1945

Love,

Kurt – Jr.

Dear people:

I’m told that you were probably never informed that I was anything other than “missing in action.” Chances are that you also failed to receive any of the letters I wrote from Germany. That leaves me a lot of explaining to do — in precis:

I’ve been a prisoner of war since December 19th, 1944, when our division was cut to ribbons by Hitler’s last desperate thrust through Luxemburg and Belgium. Seven Fanatical Panzer Divisions hit us and cut us off from the rest of Hodges’ First Army. The other American Divisions on our flanks managed to pull out: We were obliged to stay and fight. Bayonets aren’t much good against tanks: Our ammunition, food and medical supplies gave out and our casualties out-numbered those who could still fight – so we gave up. The 106th got a Presidential Citation and some British Decoration from Montgomery for it, I’m told, but I’ll be damned if it was worth it. I was one of the few who weren’t wounded. For that much thank God.

Well, the supermen marched us, without food, water or sleep to Limberg, a distance of about sixty miles, I think, where we were loaded and locked up, sixty men to each small, unventilated, unheated box car. There were no sanitary accommodations — the floors were covered with fresh cow dung. There wasn’t room for all of us to lie down. Half slept while the other half stood. We spent several days, including Christmas, on that Limberg siding. On Christmas eve the Royal Air Force bombed and strafed our unmarked train. They killed about one-hundred-and-fifty of us. We got a little water Christmas Day and moved slowly across Germany to a large P.O.W. Camp in Muhlburg, South of Berlin. We were released from the box cars on New Year’s Day. The Germans herded us through scalding delousing showers. Many men died from shock in the showers after ten days of starvation, thirst and exposure. But I didn’t.

Under the Geneva Convention, Officers and Non-commissioned Officers are not obliged to work when taken prisoner. I am, as you know, a Private. One-hundred-and-fifty such minor beings were shipped to a Dresden work camp on January 10th. I was their leader by virtue of the little German I spoke. It was our misfortune to have sadistic and fanatical guards. We were refused medical attention and clothing: We were given long hours at extremely hard labor. Our food ration was two-hundred-and-fifty grams of black bread and one pint of unseasoned potato soup each day. After desperately trying to improve our situation for two months and having been met with bland smiles I told the guards just what I was going to do to them when the Russians came. They beat me up a little. I was fired as group leader. Beatings were very small time: — one boy starved to death and the SS Troops shot two for stealing food.

On about February 14th the Americans came over, followed by the R.A.F. their combined labors killed 250,000 people in twenty-four hours and destroyed all of Dresden — possibly the world’s most beautiful city. But not me.

After that we were put to work carrying corpses from Air-Raid shelters; women, children, old men; dead from concussion, fire or suffocation. Civilians cursed us and threw rocks as we carried bodies to huge funeral pyres in the city.

When General Patton took Leipzig we were evacuated on foot to (‘the Saxony-Czechoslovakian border’?). There we remained until the war ended. Our guards deserted us. On that happy day the Russians were intent on mopping up isolated outlaw resistance in our sector. Their planes (P-39′s) strafed and bombed us, killing fourteen, but not me.

Eight of us stole a team and wagon. We traveled and looted our way through Sudetenland and Saxony for eight days, living like kings. The Russians are crazy about Americans. The Russians picked us up in Dresden. We rode from there to the American lines at Halle in Lend-Lease Ford trucks. We’ve since been flown to Le Havre.

I’m writing from a Red Cross Club in the Le Havre P.O.W. Repatriation Camp. I’m being wonderfully well feed and entertained. The state-bound ships are jammed, naturally, so I’ll have to be patient. I hope to be home in a month. Once home I’ll be given twenty-one days recuperation at Atterbury, about $600 back pay and — get this — sixty (60) days furlough.

I’ve too damned much to say, the rest will have to wait, I can’t receive mail here so don’t write.

May 29, 1945

Love,

Kurt – Jr.

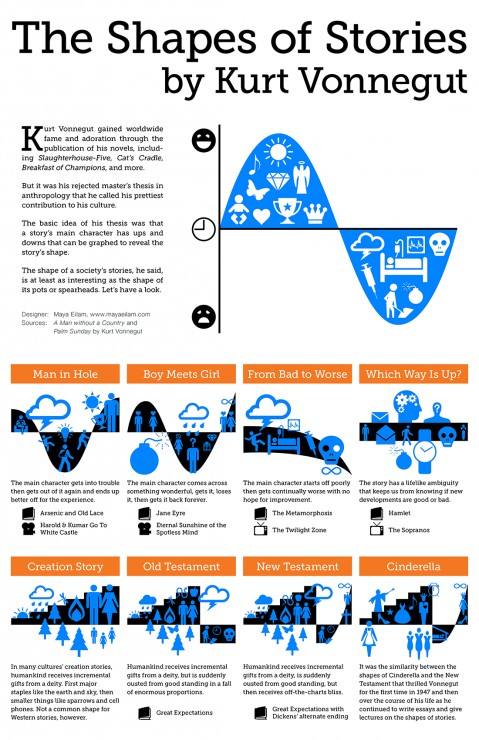

I want to share with you something I’ve learned. I’ll draw it on the blackboard behind me so you can follow more easily [draws a vertical line on the blackboard]. This is the G-I axis: good fortune-ill fortune. Death and terrible poverty, sickness down here—great prosperity, wonderful health up there. Your average state of affairs here in the middle [points to bottom, top, and middle of line respectively].

This is the B-E axis. B for beginning, E for entropy. Okay. Not every story has that very simple, very pretty shape that even a computer can understand [draws horizontal line extending from middle of G-I axis].

Now let me give you a marketing tip. The people who can afford to buy books and magazines and go to the movies don’t like to hear about people who are poor or sick, so start your story up here [indicates top of the G-I axis]. You will see this story over and over again. People love it, and it is not copyrighted. The story is “Man in Hole,” but the story needn’t be about a man or a hole. It’s: somebody gets into trouble, gets out of it again [draws line A]. It is not accidental that the line ends up higher than where it began. This is encouraging to readers.

Another is called “Boy Meets Girl,” but this needn’t be about a boy meeting a girl [begins drawing line B]. It’s: somebody, an ordinary person, on a day like any other day, comes across something perfectly wonderful: “Oh boy, this is my lucky day!” … [drawing line downward]. “Shit!” … [drawing line back up again]. And gets back up again.

Now, I don’t mean to intimidate you, but after being a chemist as an undergraduate at Cornell, after the war I went to the University of Chicago and studied anthropology, and eventually I took a masters degree in that field. Saul Bellow was in that same department, and neither one of us ever made a field trip. Although we certainly imagined some. I started going to the library in search of reports about ethnographers, preachers, and explorers—those imperialists—to find out what sorts of stories they’d collected from primitive people. It was a big mistake for me to take a degree in anthropology anyway, because I can’t stand primitive people—they’re so stupid. But anyway, I read these stories, one after another, collected from primitive people all over the world, and they were dead level, like the B-E axis here. So all right. Primitive people deserve to lose with their lousy stories. They really are backward. Look at the wonderful rise and fall of our stories.

One of the most popular stories ever told starts down here [begins line C below B-E axis]. Who is this person who’s despondent? She’s a girl of about fifteen or sixteen whose mother had died, so why wouldn’t she be low? And her father got married almost immediately to a terrible battle-axe with two mean daughters. You’ve heard it?

There’s to be a party at the palace. She has to help her two stepsisters and her dreadful stepmother get ready to go, but she herself has to stay home. Is she even sadder now? No, she’s already a broken-hearted little girl. The death of her mother is enough. Things can’t get any worse than that. So okay, they all leave for the party. Her fairy godmother shows up [draws incremental rise], gives her pantyhose, mascara, and a means of transportation to get to the party.

And when she shows up she’s the belle of the ball [draws line upward]. She is so heavily made up that her relatives don’t even recognize her. Then the clock strikes twelve, as promised, and it’s all taken away again [draws line downward]. It doesn’t take long for a clock to strike twelve times, so she drops down. Does she drop down to the same level? Hell, no. No matter what happens after that she’ll remember when the prince was in love with her and she was the belle of the ball. So she poops along, at her considerably improved level, no matter what, and the shoe fits, and she becomes off-scale happy [draws line upward and then infinity symbol].

Now there’s a Franz Kafka story [begins line D toward bottom of G-I axis]. A young man is rather unattractive and not very personable. He has disagreeable relatives and has had a lot of jobs with no chance of promotion. He doesn’t get paid enough to take his girl dancing or to go to the beer hall to have a beer with a friend. One morning he wakes up, it’s time to go to work again, and he has turned into a cockroach [draws line downward and then infinity symbol].

It’s a pessimistic story.

The question is, does this system I’ve devised help us in the evaluation of literature? Perhaps a real masterpiece cannot be crucified on a cross of this design. How about Hamlet? It’s a pretty good piece of work I’d say. Is anybody going to argue that it isn’t? I don’t have to draw a new line, because Hamlet’s situation is the same as Cinderella’s, except that the sexes are reversed.

His father has just died. He’s despondent. And right away his mother went and married his uncle, who’s a bastard. So Hamlet is going along on the same level as Cinderella when his friend Horatio comes up to him and says, “Hamlet, listen, there’s this thing up in the parapet, I think maybe you’d better talk to it. It’s your dad.” So Hamlet goes up and talks to this, you know, fairly substantial apparition there. And this thing says, “I’m your father, I was murdered, you gotta avenge me, it was your uncle did it, here’s how.”

Well, was this good news or bad news? To this day we don’t know if that ghost was really Hamlet’s father. If you have messed around with Ouija boards, you know there are malicious spirits floating around, liable to tell you anything, and you shouldn’t believe them. Madame Blavatsky, who knew more about the spirit world than anybody else, said you are a fool to take any apparition seriously, because they are often malicious and they are frequently the souls of people who were murdered, were suicides, or were terribly cheated in life in one way or another, and they are out for revenge.

So we don’t know whether this thing was really Hamlet’s father or if it was good news or bad news. And neither does Hamlet. But he says okay, I got a way to check this out. I’ll hire actors to act out the way the ghost said my father was murdered by my uncle, and I’ll put on this show and see what my uncle makes of it. So he puts on this show. And it’s not like Perry Mason. His uncle doesn’t go crazy and say, “I-I-you got me, you got me, I did it, I did it.” It flops. Neither good news nor bad news. After this flop Hamlet ends up talking with his mother when the drapes move, so he thinks his uncle is back there and he says, “All right, I am so sick of being so damn indecisive,” and he sticks his rapier through the drapery. Well, who falls out? This windbag, Polonius. This Rush Limbaugh. And Shakespeare regards him as a fool and quite disposable.

You know, dumb parents think that the advice that Polonius gave to his kids when they were going away was what parents should always tell their kids, and it’s the dumbest possible advice, and Shakespeare even thought it was hilarious.

“Neither a borrower nor a lender be.” But what else is life but endless lending and borrowing, give and take?

“This above all, to thine own self be true.” Be an egomaniac!

Neither good news nor bad news. Hamlet didn’t get arrested. He’s prince. He can kill anybody he wants. So he goes along, and finally he gets in a duel, and he’s killed. Well, did he go to heaven or did he go to hell? Quite a difference. Cinderella or Kafka’s cockroach? I don’t think Shakespeare believed in a heaven or hell any more than I do. And so we don’t know whether it’s good news or bad news.

I have just demonstrated to you that Shakespeare was as poor a storyteller as any Arapaho.

But there’s a reason we recognize Hamlet as a masterpiece: it’s that Shakespeare told us the truth, and people so rarely tell us the truth in this rise and fall here [indicates blackboard]. The truth is, we know so little about life, we don’t really know what the good news is and what the bad news is.

And if I die—God forbid—I would like to go to heaven to ask somebody in charge up there, “Hey, what was the good news and what was the bad news?”

This is the B-E axis. B for beginning, E for entropy. Okay. Not every story has that very simple, very pretty shape that even a computer can understand [draws horizontal line extending from middle of G-I axis].

Now let me give you a marketing tip. The people who can afford to buy books and magazines and go to the movies don’t like to hear about people who are poor or sick, so start your story up here [indicates top of the G-I axis]. You will see this story over and over again. People love it, and it is not copyrighted. The story is “Man in Hole,” but the story needn’t be about a man or a hole. It’s: somebody gets into trouble, gets out of it again [draws line A]. It is not accidental that the line ends up higher than where it began. This is encouraging to readers.

Another is called “Boy Meets Girl,” but this needn’t be about a boy meeting a girl [begins drawing line B]. It’s: somebody, an ordinary person, on a day like any other day, comes across something perfectly wonderful: “Oh boy, this is my lucky day!” … [drawing line downward]. “Shit!” … [drawing line back up again]. And gets back up again.

Now, I don’t mean to intimidate you, but after being a chemist as an undergraduate at Cornell, after the war I went to the University of Chicago and studied anthropology, and eventually I took a masters degree in that field. Saul Bellow was in that same department, and neither one of us ever made a field trip. Although we certainly imagined some. I started going to the library in search of reports about ethnographers, preachers, and explorers—those imperialists—to find out what sorts of stories they’d collected from primitive people. It was a big mistake for me to take a degree in anthropology anyway, because I can’t stand primitive people—they’re so stupid. But anyway, I read these stories, one after another, collected from primitive people all over the world, and they were dead level, like the B-E axis here. So all right. Primitive people deserve to lose with their lousy stories. They really are backward. Look at the wonderful rise and fall of our stories.

One of the most popular stories ever told starts down here [begins line C below B-E axis]. Who is this person who’s despondent? She’s a girl of about fifteen or sixteen whose mother had died, so why wouldn’t she be low? And her father got married almost immediately to a terrible battle-axe with two mean daughters. You’ve heard it?

There’s to be a party at the palace. She has to help her two stepsisters and her dreadful stepmother get ready to go, but she herself has to stay home. Is she even sadder now? No, she’s already a broken-hearted little girl. The death of her mother is enough. Things can’t get any worse than that. So okay, they all leave for the party. Her fairy godmother shows up [draws incremental rise], gives her pantyhose, mascara, and a means of transportation to get to the party.

And when she shows up she’s the belle of the ball [draws line upward]. She is so heavily made up that her relatives don’t even recognize her. Then the clock strikes twelve, as promised, and it’s all taken away again [draws line downward]. It doesn’t take long for a clock to strike twelve times, so she drops down. Does she drop down to the same level? Hell, no. No matter what happens after that she’ll remember when the prince was in love with her and she was the belle of the ball. So she poops along, at her considerably improved level, no matter what, and the shoe fits, and she becomes off-scale happy [draws line upward and then infinity symbol].

Now there’s a Franz Kafka story [begins line D toward bottom of G-I axis]. A young man is rather unattractive and not very personable. He has disagreeable relatives and has had a lot of jobs with no chance of promotion. He doesn’t get paid enough to take his girl dancing or to go to the beer hall to have a beer with a friend. One morning he wakes up, it’s time to go to work again, and he has turned into a cockroach [draws line downward and then infinity symbol].

It’s a pessimistic story.

The question is, does this system I’ve devised help us in the evaluation of literature? Perhaps a real masterpiece cannot be crucified on a cross of this design. How about Hamlet? It’s a pretty good piece of work I’d say. Is anybody going to argue that it isn’t? I don’t have to draw a new line, because Hamlet’s situation is the same as Cinderella’s, except that the sexes are reversed.

His father has just died. He’s despondent. And right away his mother went and married his uncle, who’s a bastard. So Hamlet is going along on the same level as Cinderella when his friend Horatio comes up to him and says, “Hamlet, listen, there’s this thing up in the parapet, I think maybe you’d better talk to it. It’s your dad.” So Hamlet goes up and talks to this, you know, fairly substantial apparition there. And this thing says, “I’m your father, I was murdered, you gotta avenge me, it was your uncle did it, here’s how.”

Well, was this good news or bad news? To this day we don’t know if that ghost was really Hamlet’s father. If you have messed around with Ouija boards, you know there are malicious spirits floating around, liable to tell you anything, and you shouldn’t believe them. Madame Blavatsky, who knew more about the spirit world than anybody else, said you are a fool to take any apparition seriously, because they are often malicious and they are frequently the souls of people who were murdered, were suicides, or were terribly cheated in life in one way or another, and they are out for revenge.

So we don’t know whether this thing was really Hamlet’s father or if it was good news or bad news. And neither does Hamlet. But he says okay, I got a way to check this out. I’ll hire actors to act out the way the ghost said my father was murdered by my uncle, and I’ll put on this show and see what my uncle makes of it. So he puts on this show. And it’s not like Perry Mason. His uncle doesn’t go crazy and say, “I-I-you got me, you got me, I did it, I did it.” It flops. Neither good news nor bad news. After this flop Hamlet ends up talking with his mother when the drapes move, so he thinks his uncle is back there and he says, “All right, I am so sick of being so damn indecisive,” and he sticks his rapier through the drapery. Well, who falls out? This windbag, Polonius. This Rush Limbaugh. And Shakespeare regards him as a fool and quite disposable.

You know, dumb parents think that the advice that Polonius gave to his kids when they were going away was what parents should always tell their kids, and it’s the dumbest possible advice, and Shakespeare even thought it was hilarious.

“Neither a borrower nor a lender be.” But what else is life but endless lending and borrowing, give and take?

“This above all, to thine own self be true.” Be an egomaniac!

Neither good news nor bad news. Hamlet didn’t get arrested. He’s prince. He can kill anybody he wants. So he goes along, and finally he gets in a duel, and he’s killed. Well, did he go to heaven or did he go to hell? Quite a difference. Cinderella or Kafka’s cockroach? I don’t think Shakespeare believed in a heaven or hell any more than I do. And so we don’t know whether it’s good news or bad news.

I have just demonstrated to you that Shakespeare was as poor a storyteller as any Arapaho.

But there’s a reason we recognize Hamlet as a masterpiece: it’s that Shakespeare told us the truth, and people so rarely tell us the truth in this rise and fall here [indicates blackboard]. The truth is, we know so little about life, we don’t really know what the good news is and what the bad news is.

And if I die—God forbid—I would like to go to heaven to ask somebody in charge up there, “Hey, what was the good news and what was the bad news?”