Unbroken

Directed by Angela Jolie

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unbroken_%28film%29

|

|

|

Louie, Mac, and Phil caught a shark and only ate its liver...Not all sharks are edible. Most commonly consumed shark varieties are dogfishes, catsharks, sand sharks, makos, and smoothhounds. Mako fish is a delicacy for their meat is salmon-coloured having a very fine quality. Mako liver is used to prepare oil that is rich in vitamins.

Mutsuhiro Watanabe (Japanese: 渡邊睦裕, January 1, 1918 – April 1, 2003) was an Imperial Japanese Army sergeant in World War II who served at POW camps in Omori, Naoetsu (present day Jōetsu, Niigata), and Mitsushima (present day Hiraoka). After Japan's defeat, the US Occupation authorities classified Watanabe as a war criminal for his mistreatment of prisoners of war (POWs), but he managed to evade arrest and was never tried in court.[1]

Prison guard Former POWs have described the frequent beatings that Watanabe administered as causing the prisoners often serious and lasting injuries. Other examples of torture commited by Watanabe include having made one officer sit in a shack, wearing only a fundoshi undergarment, for ten days in the winter, and to have tied a sixty-five-year-old prisoner to a tree for days. Watanabe allegedly ordered one man to report to him to be punched in the face every night for three weeks, and practiced judo on an appendectomy patient. His prisoners nicknamed Watanabe "The Bird". One of Watanabe's prisoners was American track star Louis Zamperini, who recalled that after one beating he saw on Watanabe's face a "soft languor.... It was an expression of sexual rapture.".[2]

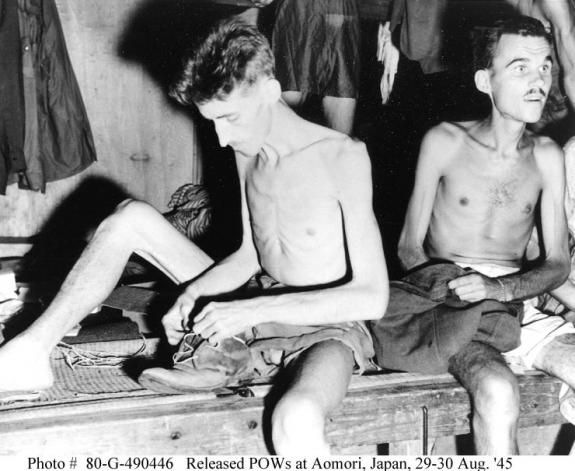

Beatings administered by Watanabe could go on for hours at a time, and would be resumed the next day. Watanabe is described as someone who received great joy from humiliating and emotionally torturing prisoners. Examples of such practice include showing prisoners letters sent to them by family members, and then burning these letters in front of the prisoners without giving them a chance to read them. Other crimes described by former prisoners include stealing supplies provided by the Red Cross for Watanabe's and other staff members private use as well as making POWs do excruciating hard slave labor while providing only 500 calories worth of food each day.

Later life In 1945, General Douglas MacArthur included Watanabe as number 23 on his list of the 40 most wanted war criminals in Japan. Watanabe went into hiding and was therefore never prosecuted even though the case against him consisted of some 250 sworn affidavits spanning more than 8 feet. While in hiding, Watanabe apparently worked on a farm and in a small grocery store. In 1956, the Japanese literary magazine Bungeishunjū published an interview with Watanabe titled アメリカに裁かれるのは厭だ! ("I do not want to be judged by America").[2] Watanabe later became a successful life insurance salesman and was reportedly wealthy, owning a $1.5 million apartment in Tokyo and a vacation condominium in Gold Coast, Australia.[2]

Prior to the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano, the CBS News program 60 Minutes interviewed Watanabe at the Hotel Okura in Tokyo as part of a feature on Zamperini, who was returning to carry the Olympic Flame torch through Naoetsu en route to Nagano. In the interview, Watanabe acknowledged beating and kicking prisoners, but was unrepentant, saying: "I treated the prisoners strictly as enemies of Japan." Watanabe refused to meet Zamperini upon request.[3]

Legacy Watanabe's abusive behavior is described in Laura Hillenbrand's book about Zamperini titled Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption (2010).[2] Watanabe also appears in Dr. Alfred A. Weinstein's memoir, Barbed Wire Surgeon, published in 1948. In 2014, Japanese musician Miyavi played Watanabe in Angelina Jolie's Unbroken, the film adaptation of Hillenbrand's book.[4]

Prison guard Former POWs have described the frequent beatings that Watanabe administered as causing the prisoners often serious and lasting injuries. Other examples of torture commited by Watanabe include having made one officer sit in a shack, wearing only a fundoshi undergarment, for ten days in the winter, and to have tied a sixty-five-year-old prisoner to a tree for days. Watanabe allegedly ordered one man to report to him to be punched in the face every night for three weeks, and practiced judo on an appendectomy patient. His prisoners nicknamed Watanabe "The Bird". One of Watanabe's prisoners was American track star Louis Zamperini, who recalled that after one beating he saw on Watanabe's face a "soft languor.... It was an expression of sexual rapture.".[2]

Beatings administered by Watanabe could go on for hours at a time, and would be resumed the next day. Watanabe is described as someone who received great joy from humiliating and emotionally torturing prisoners. Examples of such practice include showing prisoners letters sent to them by family members, and then burning these letters in front of the prisoners without giving them a chance to read them. Other crimes described by former prisoners include stealing supplies provided by the Red Cross for Watanabe's and other staff members private use as well as making POWs do excruciating hard slave labor while providing only 500 calories worth of food each day.

Later life In 1945, General Douglas MacArthur included Watanabe as number 23 on his list of the 40 most wanted war criminals in Japan. Watanabe went into hiding and was therefore never prosecuted even though the case against him consisted of some 250 sworn affidavits spanning more than 8 feet. While in hiding, Watanabe apparently worked on a farm and in a small grocery store. In 1956, the Japanese literary magazine Bungeishunjū published an interview with Watanabe titled アメリカに裁かれるのは厭だ! ("I do not want to be judged by America").[2] Watanabe later became a successful life insurance salesman and was reportedly wealthy, owning a $1.5 million apartment in Tokyo and a vacation condominium in Gold Coast, Australia.[2]

Prior to the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano, the CBS News program 60 Minutes interviewed Watanabe at the Hotel Okura in Tokyo as part of a feature on Zamperini, who was returning to carry the Olympic Flame torch through Naoetsu en route to Nagano. In the interview, Watanabe acknowledged beating and kicking prisoners, but was unrepentant, saying: "I treated the prisoners strictly as enemies of Japan." Watanabe refused to meet Zamperini upon request.[3]

Legacy Watanabe's abusive behavior is described in Laura Hillenbrand's book about Zamperini titled Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption (2010).[2] Watanabe also appears in Dr. Alfred A. Weinstein's memoir, Barbed Wire Surgeon, published in 1948. In 2014, Japanese musician Miyavi played Watanabe in Angelina Jolie's Unbroken, the film adaptation of Hillenbrand's book.[4]

From Wikipedia

Japanese attitudes to surrender During the 1920s and 1930s, the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) adopted an ethos which required soldiers to fight to the death rather than surrender.[6] This policy reflected the practices of Japanese warfare in the pre-modern era.[7] During the Meiji period the Japanese government adopted western policies towards POWs, and few of the Japanese personnel who surrendered in the Russo-Japanese War were punished at the end of the war. Prisoners captured by Japanese forces during this and the First Sino-Japanese War and World War I were also treated in accordance with international standards.[8] Attitudes towards surrender hardened after World War I. While Japan signed the 1929 Geneva Convention covering treatment of POWs, it did not ratify the agreement, claiming that surrender was contrary to the beliefs of Japanese soldiers. This attitude was reinforced by the indoctrination of young people.[9]

A Japanese soldier in the sea off Cape Endaiadere, New Guinea on 18 December 1942 holding a hand grenade to his head moments before using it to commit suicide. The Australian soldier on the beach had called on him to surrender.[10][11] The Japanese military's attitude towards surrender was institutionalized in the 1941 "Code of Battlefield Conduct" (Senjinkun), which was issued to all Japanese soldiers. This document sought to establish standards of behavior for Japanese troops and improve discipline and morale within the Army, and included a prohibition against being taken prisoner.[12] The Japanese Government accompanied the Senjinkun's implementation with a propaganda campaign which celebrated people who had fought to the death rather than surrender during Japan's wars.[13] While the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) did not issue a document equivalent to the Senjinkun, naval personnel were expected to exhibit similar behavior and not surrender.[14] Most Japanese military personnel were told that they would be killed or tortured by the Allies if they were taken prisoner.[15] The Army's Field Service Regulations were also modified in 1940 to replace a provision which stated that seriously wounded personnel in field hospitals came under the protection of the 1929 Geneva Convention for the Sick and Wounded Armies in the Field with a requirement that the wounded not fall into enemy hands. During the war, this led to wounded personnel being either killed by medical officers or given grenades to commit suicide.[16]

Not all Japanese military personnel chose to follow the precepts set out on the Senjinkun. Those who chose to surrender did so for a range of reasons including not believing that suicide was appropriate or lacking the courage to commit the act, bitterness towards officers, and Allied propaganda promising good treatment.[19] During the later years of the war Japanese troops' morale deteriorated as a result of Allied victories, leading to an increase in the number who were prepared to surrender or desert.[20] During the Battle of Okinawa, 11,250 Japanese military personnel (including 3,581 unarmed labourers) surrendered between April and July 1945, representing 12 percent of the force deployed for the defense of the island. Many of these men were recently-conscripted members of Boeitai home guard units who had not received the same indoctrination as regular Army personnel, but substantial numbers of IJA soldiers also surrendered.[21]

Japanese soldiers' reluctance to surrender was also influenced by a perception that Allied forces would kill them if they did surrender, and historian Niall Ferguson has argued that this had a more important influence in discouraging surrenders than the fear of disciplinary action or dishonor.[4] In addition, the Japanese public was aware that US troops sometimes mutilated Japanese casualties and sent trophies made out of body-parts home from media reports of two high-profile incidents in 1944 in which a letter-opener carved from a bone of a Japanese soldier was presented to President Roosevelt and a photo of the skull of a Japanese soldier which had been sent home by a US soldier was published in the magazine Life. In these reports Americans were portrayed as "deranged, primitive, racist and inhuman".[22] Hoyt in "Japan’s war: the great Pacific conflict" argues that the Allied practice of taking bones from Japanese corpses home as souvenirs was exploited by Japanese propaganda very effectively, and "contributed to a preference to death over surrender and occupation, shown, for example, in the mass civilian suicides on Saipan and Okinawa after the Allied landings".[22]

The causes of the phenomenon that Japanese often continued to fight even in hopeless situations has been traced to a combination of Shinto, Messhi hoko (self-sacrifice for the sake of group), and Bushido. However, a factor equally strong or even stronger to those, was the fear of torture after capture. This fear grew out of years of battle experiences in China, where the Chinese guerrillas were considered expert torturers, and this fear was projected onto the American soldiers who also were expected to torture and kill surrendered Japanese.[23] During the Pacific War the majority of Japanese military personnel did not believe that the Allies treated prisoners correctly, and even a majority of those who surrendered expected to be killed.[24]

Allied attitudes A Japanese soldier surrendering to three US Marines in the Marshall Islands during January 1944. The Western Allies sought to treat captured Japanese in accordance with international agreements which governed the treatment of POWs.[18] Shortly after the outbreak of Pacific War in December 1941, the British and United States governments transmitted a message to the Japanese government through Swiss intermediaries asking if Japan would abide by the 1929 Geneva Convention. The Japanese Government responded stating that while it had not signed the convention, Japan would treat POWs in accordance with its terms; in effect though, Japan had willfully ignored the convention's requirements. While the Western Allies notified the Japanese government of the identities of Japanese POWs in accordance with the Geneva Convention's requirements, this information was not passed onto the families of the captured men as the Japanese government wished to maintain that none of its soldiers had been taken prisoner.[25]

Allied combatants were reluctant to take Japanese prisoners at the start of the Pacific War. During the first two years following the US entry into the war, US combatants were generally unwilling to accept the surrender of Japanese soldiers due to a combination of racist attitudes and anger at Japan's atrocities committed against US and Allied nationals and its widespread mistreatment or summary execution of Allied prisoners of war.[18][26] Australian soldiers were also reluctant to take Japanese prisoners for similar reasons.[27] Incidents in which Japanese soldiers booby-trapped their dead and wounded or pretended to surrender in order to lure Allied combatants into ambushes were well known within the Allied militaries and also hardened attitudes against seeking the surrender of Japanese on the battlefield.[28] As a result, Allied troops believed that their Japanese opponents would not surrender and that any attempts to surrender were deceptive;[29] for instance, the Australian jungle warfare school advised soldiers to shoot any Japanese troops who had their hands closed while surrendering.[27] Furthermore, in many instances, Japanese soldiers who had surrendered were killed on the front line or while being taken to POW compounds.[30] The nature of jungle warfare also contributed to prisoners not being taken, as many battles were fought at close ranges where participants "often had no choice but to shoot first and ask questions later".[31]

Two surrendered Japanese soldiers with a Japanese civilian and two US soldiers on Okinawa. The Japanese soldier on the left is reading a propaganda leaflet. Despite the attitudes of combat troops and nature of the fighting, Allied militaries made systematic efforts to take Japanese prisoners throughout the war. Each US Army division was assigned a team of Japanese Americans whose duties included attempting to persuade Japanese personnel to surrender.[32] Allied forces mounted an extensive psychological warfare campaign against their Japanese opponents to lower their morale and encourage surrender.[33] This included dropping copies of the Geneva Conventions and 'surrender passes' on Japanese positions.[34] This campaign was undermined by Allied troops' reluctance to take prisoners, however.[35] As a result, from May 1944, senior US Army commanders authorized and endorsed educational programs which aimed to change the attitudes of front line troops. These programs highlighted the intelligence which could be gained from Japanese POWs, the need to honor surrender leaflets, and the benefits which could be gained by encouraging Japanese forces to not fight to the last man. The programs were partially successful, and contributed to US troops taking more prisoners. In addition, soldiers who witnessed Japanese troops surrender were more willing to take prisoners themselves.[36]

Japanese POW bathing on board the USS New Jersey, December 1944. Survivors of ships sunk by Allied submarines frequently refused to surrender, and many of the prisoners who were captured by submariners were taken by force. US Navy submarines were occasionally ordered to obtain prisoners for intelligence purposes, and formed special teams of personnel for this purpose.[37] Overall, however, Allied submariners usually did not attempt to take prisoners, and the number of Japanese personnel they captured was relatively small. The submarines which took prisoners normally did so towards the end of their patrols so that they did not have to be guarded for a long time.[38]

Allied forces continued to kill many Japanese personnel who were attempting to surrender throughout the war.[39] It is likely that more Japanese soldiers would have surrendered if they had not believed that they would be killed by the Allies while trying to do so.[2] Fear of being killed after surrendering was one of the main factors which influenced Japanese troops to fight to the death, and a wartime US Office of Wartime Information report stated that it may have been more important than fear of disgrace and a desire to die for Japan.[40] Instances of Japanese personnel being killed while attempting to surrender are not well documented, though anecdotal accounts provide evidence that this occurred.[26]

Intelligence gathered from Japanese POWs A US surrender leaflet depicting Japanese POWs. The leaflet's wording was changed from 'I surrender' to 'I cease resistance' at the suggestion of POWs.[49] The Allies gained considerable quantities of intelligence from Japanese POWs. Because they had been indoctrinated to believe that by surrendering they had broken all ties with Japan, many captured personnel provided their interrogators with information on the Japanese military.[41] Australian and US troops and senior officers commonly believed that captured Japanese troops were very unlikely to divulge any information of military value, leading to them having little motivation to take prisoners.[50] This view proved incorrect, however, and many Japanese POWs provided valuable intelligence during interrogations. Few Japanese were aware of the Geneva Convention and the rights it gave prisoners to not respond to questioning. Moreover, the POWs felt that by surrendering they had lost all their rights. The prisoners appreciated the opportunity to converse with Japanese-speaking Americans and felt that the food, clothing and medical treatment they were provided with meant that they owed favours to their captors. The Allied interrogators found that exaggerating the amount they knew about the Japanese forces and asking the POWs to 'confirm' details was also a successful approach. As a result of these factors, Japanese POWs were often cooperative and truthful during interrogation sessions.[51]

Japanese POWs were interrogated multiple times during their captivity. Most Japanese soldiers were interrogated by intelligence officers of the battalion or regiment which had captured them for information which could be used by these units. Following this they were rapidly moved to rear areas where they were interrogated by successive echelons of the Allied military. They were also questioned once they reached a POW camp in Australia, New Zealand, India or the United States. These interrogations were painful and stressful for the POWs.[52] Force was not used by Allied interrogators, though on one occasion headquarters personnel of the US 40th Infantry Division debated, but ultimately decided against, administering sodium penthanol to a senior non-commissioned officer.[53]

Some Japanese POWs also played an important role in helping the Allied militaries develop propaganda and politically indoctrinate their fellow prisoners.[54] This included developing propaganda leaflets and loudspeaker broadcasts which were designed to encourage other Japanese personnel to surrender. The wording of this material sought to overcome the indoctrination which Japanese soldiers had received by stating that they should "cease resistance" rather than "surrender".[55] POWs also provided advice on the wording for propaganda leaflets which were dropped on Japanese cities by heavy bombers in the final months of the war.[56]

Allied prisoner of war camps Japanese POWs held in Allied prisoner of war camps were treated in accordance with the Geneva Convention.[57] By 1943 the Allied governments were aware that personnel who had been captured by the Japanese military were being held in harsh conditions. In an attempt to win better treatment for their POWs, the Allies made extensive efforts to notify the Japanese government of the good conditions in Allied POW camps.[58] This was not successful, however, as the Japanese government refused to recognise the existence of captured Japanese military personnel.[59] Nevertheless, Japanese POWs in Allied camps continued to be treated in accordance with the Geneva Conventions until the end of the war.[60]

Most Japanese captured by US forces after September 1942 were turned over to Australia or New Zealand for internment. The United States provided these countries with aid through the Lend Lease program to cover the costs of maintaining the prisoners, and retained responsibility for repatriating the men to Japan at the end of the war. Prisoners captured in the central Pacific or who were believed to have particular intelligence value were held in camps in the United States.[61]

Japanese POWs practice baseball near their quarters, several weeks before the Cowra breakout. This photograph was taken with the intention of using it in propaganda leaflets, to be dropped on Japanese-held areas in the Asia-Pacific region.[62] Prisoners who were thought to possess significant technical or strategic information were brought to specialist intelligence-gathering facilities at Fort Hunt, Virginia or Camp Tracy, California. After arriving in these camps, the prisoners were interrogated again, and their conversations were wiretapped and analysed. Some of the conditions at Camp Tracy violated Geneva Convention requirements, such as insufficient exercise time being provided. However, prisoners at this camp were given special benefits, such as high quality food and access to a shop, and the interrogation sessions were relatively relaxed. The continuous wiretapping at both locations may have also violated the spirit of the Geneva Convention.[63]

Japanese POWs generally adjusted to life in prison camps and few attempted to escape.[64] There were several incidents at POW camps, however. On 25 February 1943, POWs at the Featherston prisoner of war camp in New Zealand staged a strike after being ordered to work. The protest turned violent when the camp's deputy commander shot one of the protest's leaders. The POWs then attacked the other guards, who opened fire and killed 48 prisoners and wounded another 74. Conditions at the camp were subsequently improved, leading to good relations between the Japanese and their New Zealand guards for the remainder of the war.[65] More seriously, on 5 August 1944, Japanese POWs in a camp near Cowra, Australia attempted to escape. During the fighting between the POWs and their guards 257 Japanese and four Australians were killed.[66] Other confrontations between Japanese POWs and their guards occurred at Camp McCoy in Wisconsin during May 1944 as well as a camp in Bikaner, India during 1945; these did not result in any fatalities.[67] In addition, 24 Japanese POWs killed themselves at Camp Paita, New Caledonia in January 1944 after a planned uprising was foiled.[68] News of the incidents at Cowra and Featherston was suppressed in Japan,[69] but the Japanese Government lodged protests with the Australian and New Zealand governments as a propaganda tactic. This was the only time that the Japanese Government officially recognized that some members of the country's military had surrendered.[70]

The Allies distributed photographs of Japanese POWs in camps to induce other Japanese personnel to surrender. This tactic was initially rejected by General MacArthur when it was proposed to him in mid-1943 on the grounds that it violated the Hague and Geneva Conventions, and the fear of being identified after surrendering could harden Japanese resistance. MacArthur reversed his position in December of that year, however, but only allowed the publication of photos that did not identify individual POWs. He also directed that the photos "should be truthful and factual and not designed to exaggerate".[71]

Japanese attitudes to surrender During the 1920s and 1930s, the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) adopted an ethos which required soldiers to fight to the death rather than surrender.[6] This policy reflected the practices of Japanese warfare in the pre-modern era.[7] During the Meiji period the Japanese government adopted western policies towards POWs, and few of the Japanese personnel who surrendered in the Russo-Japanese War were punished at the end of the war. Prisoners captured by Japanese forces during this and the First Sino-Japanese War and World War I were also treated in accordance with international standards.[8] Attitudes towards surrender hardened after World War I. While Japan signed the 1929 Geneva Convention covering treatment of POWs, it did not ratify the agreement, claiming that surrender was contrary to the beliefs of Japanese soldiers. This attitude was reinforced by the indoctrination of young people.[9]

A Japanese soldier in the sea off Cape Endaiadere, New Guinea on 18 December 1942 holding a hand grenade to his head moments before using it to commit suicide. The Australian soldier on the beach had called on him to surrender.[10][11] The Japanese military's attitude towards surrender was institutionalized in the 1941 "Code of Battlefield Conduct" (Senjinkun), which was issued to all Japanese soldiers. This document sought to establish standards of behavior for Japanese troops and improve discipline and morale within the Army, and included a prohibition against being taken prisoner.[12] The Japanese Government accompanied the Senjinkun's implementation with a propaganda campaign which celebrated people who had fought to the death rather than surrender during Japan's wars.[13] While the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) did not issue a document equivalent to the Senjinkun, naval personnel were expected to exhibit similar behavior and not surrender.[14] Most Japanese military personnel were told that they would be killed or tortured by the Allies if they were taken prisoner.[15] The Army's Field Service Regulations were also modified in 1940 to replace a provision which stated that seriously wounded personnel in field hospitals came under the protection of the 1929 Geneva Convention for the Sick and Wounded Armies in the Field with a requirement that the wounded not fall into enemy hands. During the war, this led to wounded personnel being either killed by medical officers or given grenades to commit suicide.[16]

Not all Japanese military personnel chose to follow the precepts set out on the Senjinkun. Those who chose to surrender did so for a range of reasons including not believing that suicide was appropriate or lacking the courage to commit the act, bitterness towards officers, and Allied propaganda promising good treatment.[19] During the later years of the war Japanese troops' morale deteriorated as a result of Allied victories, leading to an increase in the number who were prepared to surrender or desert.[20] During the Battle of Okinawa, 11,250 Japanese military personnel (including 3,581 unarmed labourers) surrendered between April and July 1945, representing 12 percent of the force deployed for the defense of the island. Many of these men were recently-conscripted members of Boeitai home guard units who had not received the same indoctrination as regular Army personnel, but substantial numbers of IJA soldiers also surrendered.[21]

Japanese soldiers' reluctance to surrender was also influenced by a perception that Allied forces would kill them if they did surrender, and historian Niall Ferguson has argued that this had a more important influence in discouraging surrenders than the fear of disciplinary action or dishonor.[4] In addition, the Japanese public was aware that US troops sometimes mutilated Japanese casualties and sent trophies made out of body-parts home from media reports of two high-profile incidents in 1944 in which a letter-opener carved from a bone of a Japanese soldier was presented to President Roosevelt and a photo of the skull of a Japanese soldier which had been sent home by a US soldier was published in the magazine Life. In these reports Americans were portrayed as "deranged, primitive, racist and inhuman".[22] Hoyt in "Japan’s war: the great Pacific conflict" argues that the Allied practice of taking bones from Japanese corpses home as souvenirs was exploited by Japanese propaganda very effectively, and "contributed to a preference to death over surrender and occupation, shown, for example, in the mass civilian suicides on Saipan and Okinawa after the Allied landings".[22]

The causes of the phenomenon that Japanese often continued to fight even in hopeless situations has been traced to a combination of Shinto, Messhi hoko (self-sacrifice for the sake of group), and Bushido. However, a factor equally strong or even stronger to those, was the fear of torture after capture. This fear grew out of years of battle experiences in China, where the Chinese guerrillas were considered expert torturers, and this fear was projected onto the American soldiers who also were expected to torture and kill surrendered Japanese.[23] During the Pacific War the majority of Japanese military personnel did not believe that the Allies treated prisoners correctly, and even a majority of those who surrendered expected to be killed.[24]

Allied attitudes A Japanese soldier surrendering to three US Marines in the Marshall Islands during January 1944. The Western Allies sought to treat captured Japanese in accordance with international agreements which governed the treatment of POWs.[18] Shortly after the outbreak of Pacific War in December 1941, the British and United States governments transmitted a message to the Japanese government through Swiss intermediaries asking if Japan would abide by the 1929 Geneva Convention. The Japanese Government responded stating that while it had not signed the convention, Japan would treat POWs in accordance with its terms; in effect though, Japan had willfully ignored the convention's requirements. While the Western Allies notified the Japanese government of the identities of Japanese POWs in accordance with the Geneva Convention's requirements, this information was not passed onto the families of the captured men as the Japanese government wished to maintain that none of its soldiers had been taken prisoner.[25]

Allied combatants were reluctant to take Japanese prisoners at the start of the Pacific War. During the first two years following the US entry into the war, US combatants were generally unwilling to accept the surrender of Japanese soldiers due to a combination of racist attitudes and anger at Japan's atrocities committed against US and Allied nationals and its widespread mistreatment or summary execution of Allied prisoners of war.[18][26] Australian soldiers were also reluctant to take Japanese prisoners for similar reasons.[27] Incidents in which Japanese soldiers booby-trapped their dead and wounded or pretended to surrender in order to lure Allied combatants into ambushes were well known within the Allied militaries and also hardened attitudes against seeking the surrender of Japanese on the battlefield.[28] As a result, Allied troops believed that their Japanese opponents would not surrender and that any attempts to surrender were deceptive;[29] for instance, the Australian jungle warfare school advised soldiers to shoot any Japanese troops who had their hands closed while surrendering.[27] Furthermore, in many instances, Japanese soldiers who had surrendered were killed on the front line or while being taken to POW compounds.[30] The nature of jungle warfare also contributed to prisoners not being taken, as many battles were fought at close ranges where participants "often had no choice but to shoot first and ask questions later".[31]

Two surrendered Japanese soldiers with a Japanese civilian and two US soldiers on Okinawa. The Japanese soldier on the left is reading a propaganda leaflet. Despite the attitudes of combat troops and nature of the fighting, Allied militaries made systematic efforts to take Japanese prisoners throughout the war. Each US Army division was assigned a team of Japanese Americans whose duties included attempting to persuade Japanese personnel to surrender.[32] Allied forces mounted an extensive psychological warfare campaign against their Japanese opponents to lower their morale and encourage surrender.[33] This included dropping copies of the Geneva Conventions and 'surrender passes' on Japanese positions.[34] This campaign was undermined by Allied troops' reluctance to take prisoners, however.[35] As a result, from May 1944, senior US Army commanders authorized and endorsed educational programs which aimed to change the attitudes of front line troops. These programs highlighted the intelligence which could be gained from Japanese POWs, the need to honor surrender leaflets, and the benefits which could be gained by encouraging Japanese forces to not fight to the last man. The programs were partially successful, and contributed to US troops taking more prisoners. In addition, soldiers who witnessed Japanese troops surrender were more willing to take prisoners themselves.[36]

Japanese POW bathing on board the USS New Jersey, December 1944. Survivors of ships sunk by Allied submarines frequently refused to surrender, and many of the prisoners who were captured by submariners were taken by force. US Navy submarines were occasionally ordered to obtain prisoners for intelligence purposes, and formed special teams of personnel for this purpose.[37] Overall, however, Allied submariners usually did not attempt to take prisoners, and the number of Japanese personnel they captured was relatively small. The submarines which took prisoners normally did so towards the end of their patrols so that they did not have to be guarded for a long time.[38]

Allied forces continued to kill many Japanese personnel who were attempting to surrender throughout the war.[39] It is likely that more Japanese soldiers would have surrendered if they had not believed that they would be killed by the Allies while trying to do so.[2] Fear of being killed after surrendering was one of the main factors which influenced Japanese troops to fight to the death, and a wartime US Office of Wartime Information report stated that it may have been more important than fear of disgrace and a desire to die for Japan.[40] Instances of Japanese personnel being killed while attempting to surrender are not well documented, though anecdotal accounts provide evidence that this occurred.[26]

Intelligence gathered from Japanese POWs A US surrender leaflet depicting Japanese POWs. The leaflet's wording was changed from 'I surrender' to 'I cease resistance' at the suggestion of POWs.[49] The Allies gained considerable quantities of intelligence from Japanese POWs. Because they had been indoctrinated to believe that by surrendering they had broken all ties with Japan, many captured personnel provided their interrogators with information on the Japanese military.[41] Australian and US troops and senior officers commonly believed that captured Japanese troops were very unlikely to divulge any information of military value, leading to them having little motivation to take prisoners.[50] This view proved incorrect, however, and many Japanese POWs provided valuable intelligence during interrogations. Few Japanese were aware of the Geneva Convention and the rights it gave prisoners to not respond to questioning. Moreover, the POWs felt that by surrendering they had lost all their rights. The prisoners appreciated the opportunity to converse with Japanese-speaking Americans and felt that the food, clothing and medical treatment they were provided with meant that they owed favours to their captors. The Allied interrogators found that exaggerating the amount they knew about the Japanese forces and asking the POWs to 'confirm' details was also a successful approach. As a result of these factors, Japanese POWs were often cooperative and truthful during interrogation sessions.[51]

Japanese POWs were interrogated multiple times during their captivity. Most Japanese soldiers were interrogated by intelligence officers of the battalion or regiment which had captured them for information which could be used by these units. Following this they were rapidly moved to rear areas where they were interrogated by successive echelons of the Allied military. They were also questioned once they reached a POW camp in Australia, New Zealand, India or the United States. These interrogations were painful and stressful for the POWs.[52] Force was not used by Allied interrogators, though on one occasion headquarters personnel of the US 40th Infantry Division debated, but ultimately decided against, administering sodium penthanol to a senior non-commissioned officer.[53]

Some Japanese POWs also played an important role in helping the Allied militaries develop propaganda and politically indoctrinate their fellow prisoners.[54] This included developing propaganda leaflets and loudspeaker broadcasts which were designed to encourage other Japanese personnel to surrender. The wording of this material sought to overcome the indoctrination which Japanese soldiers had received by stating that they should "cease resistance" rather than "surrender".[55] POWs also provided advice on the wording for propaganda leaflets which were dropped on Japanese cities by heavy bombers in the final months of the war.[56]

Allied prisoner of war camps Japanese POWs held in Allied prisoner of war camps were treated in accordance with the Geneva Convention.[57] By 1943 the Allied governments were aware that personnel who had been captured by the Japanese military were being held in harsh conditions. In an attempt to win better treatment for their POWs, the Allies made extensive efforts to notify the Japanese government of the good conditions in Allied POW camps.[58] This was not successful, however, as the Japanese government refused to recognise the existence of captured Japanese military personnel.[59] Nevertheless, Japanese POWs in Allied camps continued to be treated in accordance with the Geneva Conventions until the end of the war.[60]

Most Japanese captured by US forces after September 1942 were turned over to Australia or New Zealand for internment. The United States provided these countries with aid through the Lend Lease program to cover the costs of maintaining the prisoners, and retained responsibility for repatriating the men to Japan at the end of the war. Prisoners captured in the central Pacific or who were believed to have particular intelligence value were held in camps in the United States.[61]

Japanese POWs practice baseball near their quarters, several weeks before the Cowra breakout. This photograph was taken with the intention of using it in propaganda leaflets, to be dropped on Japanese-held areas in the Asia-Pacific region.[62] Prisoners who were thought to possess significant technical or strategic information were brought to specialist intelligence-gathering facilities at Fort Hunt, Virginia or Camp Tracy, California. After arriving in these camps, the prisoners were interrogated again, and their conversations were wiretapped and analysed. Some of the conditions at Camp Tracy violated Geneva Convention requirements, such as insufficient exercise time being provided. However, prisoners at this camp were given special benefits, such as high quality food and access to a shop, and the interrogation sessions were relatively relaxed. The continuous wiretapping at both locations may have also violated the spirit of the Geneva Convention.[63]

Japanese POWs generally adjusted to life in prison camps and few attempted to escape.[64] There were several incidents at POW camps, however. On 25 February 1943, POWs at the Featherston prisoner of war camp in New Zealand staged a strike after being ordered to work. The protest turned violent when the camp's deputy commander shot one of the protest's leaders. The POWs then attacked the other guards, who opened fire and killed 48 prisoners and wounded another 74. Conditions at the camp were subsequently improved, leading to good relations between the Japanese and their New Zealand guards for the remainder of the war.[65] More seriously, on 5 August 1944, Japanese POWs in a camp near Cowra, Australia attempted to escape. During the fighting between the POWs and their guards 257 Japanese and four Australians were killed.[66] Other confrontations between Japanese POWs and their guards occurred at Camp McCoy in Wisconsin during May 1944 as well as a camp in Bikaner, India during 1945; these did not result in any fatalities.[67] In addition, 24 Japanese POWs killed themselves at Camp Paita, New Caledonia in January 1944 after a planned uprising was foiled.[68] News of the incidents at Cowra and Featherston was suppressed in Japan,[69] but the Japanese Government lodged protests with the Australian and New Zealand governments as a propaganda tactic. This was the only time that the Japanese Government officially recognized that some members of the country's military had surrendered.[70]

The Allies distributed photographs of Japanese POWs in camps to induce other Japanese personnel to surrender. This tactic was initially rejected by General MacArthur when it was proposed to him in mid-1943 on the grounds that it violated the Hague and Geneva Conventions, and the fear of being identified after surrendering could harden Japanese resistance. MacArthur reversed his position in December of that year, however, but only allowed the publication of photos that did not identify individual POWs. He also directed that the photos "should be truthful and factual and not designed to exaggerate".[71]

Story of Makin Island--Now known as Butaritari in the Pacific Ocean

BeriBeri

B-1 Deficiency/ Thiamine

B-1 deficiency disease called beriberi affects the peripheral nervous system (polyneuritis) and/or the cardiovascular system. Thiamine deficiency has a potentially fatal outcome if it remains untreated.[1] In less severe cases, nonspecific signs include malaise, weight loss, irritability and confusion.

Thiamine is found in a wide variety of foods at low concentrations. Yeast, yeast extract, and pork are the most highly concentrated sources of thiamine.[citation needed] In general, cereal grains are the most important dietary sources of thiamine, by virtue of their ubiquity. Of these, whole grains contain more thiamine than refined grains, as thiamine is found mostly in the outer layers of the grain and in the germ (which are removed during the refining process). For example, 100 g of whole-wheat flour contains 0.55 mg of thiamine, while 100 g of white flour contains only 0.06 mg of thiamine. In the US, processed flour must be enriched with thiamine mononitrate (along with niacin, ferrous iron, riboflavin, and folic acid) to replace that lost in processing.

In Australia, thiamine, folic acid, and iodised salt are added for the same reason.[12]

Zamp/Unbroken

5 Key Lessons Every Entrepreneur Can Learn From 'Unbroken' Louis Zamperini Today's January 08, 2015

Louis ZamperiniImage credit: WikipediaUnbroken could be one of the most influential books you read and films you watch this year. What does a film about the olympian, World War II bombardier and prisoner of war have to do with being an entrepreneur? If you’ve been exposed to the life of Louis Zamperini then you already know: this guy had guts. He led an extraordinary life and refused to give up in any situation. Entrepreneurship is based on the same defining character traits that Zamperini exemplified throughout his life.

Here are five of the key lessons you can learn from Zamperini.

1. Thank your lucky stars it’s hard.Zamperini didn’t grow up with any special advantages or skills. In fact in many ways, he was at a disadvantage. His family came to California when Zamperini was a kid and he spoke no English, making him an easy target for bullying. He got in a lot of trouble in his youth. He worked hard to train and become a runner, a pursuit that eventually took him to the Olympics.

Related: A Navy SEAL's 5 Entrepreneurial Leadership Lessons From 2014

Whether it’s truth or fable, the oft-repeated line in the film is, “If you can take it, you can make it.” That ability to take the challenges and hardships life throws your way is what defines an entrepreneur. Don’t lament the hurdles that lie in front of you as an entrepreneur: embrace them. Run toward the conflict and rise to the tasks at hand.

Innovation comes through solving the world’s problems, not by having an easy answer to an easy existence. Be glad it’s hard: that’s why you’ll be so good.

2. Great risks mean greater rewards.It’s crucial as an entrepreneur to engage in small, calculated and continuous risks. Your ability to take and survive risks will help build up your confidence in yourself. Your risks will also develop the courage you’ll need to face fear in the future when it comes time to take the bigger risks.

Zamperini certainly understood that taking risks sometimes meant failing, but ultimately meant big rewards. He took the risks necessary in running to make it to the Olympics and during his days as a POW to survive the war. Taking risks is part of the entrepreneur’s path and the more you develop the ability to be comfortable with being uncomfortable, the greater your long-term rewards will be in your life.

3. Failure is a huge part of the journey.Never let your failures define you or you’ve lost the game. Zamperini was shaping up to be a total failure as a kid. He was getting in fights, drinking by age eight, robbing strangers and neighbors alike and in pretty much every other way misbehaving. By the time he was a teen his parents knew the local police very well. That’s not what you’d call a model start, but with the right support from others and initiative from himself, Zamperini turned things around. It would’ve been easy to give up and define Zamperini as a failure, a lost cause and a bad bet.

Where are you in your entrepreneurial journey? Don’t let others cast the die and define your success. Never let failure define you. You can always find the right support and you can always, always take the initiative to keep improving. An entrepreneur’s path is never straightforward, simple or easy. Embrace the failures you’ve faced and keep moving forward.

Related: 7 Entrepreneurial Lessons a 'Happy Days' Star Learned From an Unlikely Mentor

4. The right support makes all the difference.Speaking of support, it’s debatable whether Zamperini would’ve reached his Olympic success without the support of the right mentors. It wasn’t just his parents that didn’t give up on him during his misspent youth, but his brother, the school’s track coach and even the police became active mentors in coaching Zamperini into a different path that eventually led him to the Olympics.

Surrounding yourself with the right people who believe in you, support you and will rally for you when you’re off track will get you far as an entrepreneur. Likewise, remember that you can give that support and encouragement to other entrepreneurs and up-and-comers in your startup communities.

When Zamperini was stranded in a life raft with the two other survivors of the crashed flight, and later in the barracks of the POW camp, he would talk about his mother’s cooking and other fond memories to improve morale. He actively lent support to the men to keep spirits high.

We all need people to believe in us to help us achieve our best. So get yourself in the right supportive environment and lend a hand to those in need of your mentoring as well.

5. Never give up.Zamperini didn’t just embody the message of never giving up, he literally wrote the book on it. At 97 years old he published and co-authored the book, Don’t Give Up, Don’t Give In: Lessons From An Extraordinary Life. If anyone is qualified to give you advice, wisdom and insights into the indomitable spirit you’ll need in entrepreneurship and in life, it’s Zamperini.

Louis ZamperiniImage credit: WikipediaUnbroken could be one of the most influential books you read and films you watch this year. What does a film about the olympian, World War II bombardier and prisoner of war have to do with being an entrepreneur? If you’ve been exposed to the life of Louis Zamperini then you already know: this guy had guts. He led an extraordinary life and refused to give up in any situation. Entrepreneurship is based on the same defining character traits that Zamperini exemplified throughout his life.

Here are five of the key lessons you can learn from Zamperini.

1. Thank your lucky stars it’s hard.Zamperini didn’t grow up with any special advantages or skills. In fact in many ways, he was at a disadvantage. His family came to California when Zamperini was a kid and he spoke no English, making him an easy target for bullying. He got in a lot of trouble in his youth. He worked hard to train and become a runner, a pursuit that eventually took him to the Olympics.

Related: A Navy SEAL's 5 Entrepreneurial Leadership Lessons From 2014

Whether it’s truth or fable, the oft-repeated line in the film is, “If you can take it, you can make it.” That ability to take the challenges and hardships life throws your way is what defines an entrepreneur. Don’t lament the hurdles that lie in front of you as an entrepreneur: embrace them. Run toward the conflict and rise to the tasks at hand.

Innovation comes through solving the world’s problems, not by having an easy answer to an easy existence. Be glad it’s hard: that’s why you’ll be so good.

2. Great risks mean greater rewards.It’s crucial as an entrepreneur to engage in small, calculated and continuous risks. Your ability to take and survive risks will help build up your confidence in yourself. Your risks will also develop the courage you’ll need to face fear in the future when it comes time to take the bigger risks.

Zamperini certainly understood that taking risks sometimes meant failing, but ultimately meant big rewards. He took the risks necessary in running to make it to the Olympics and during his days as a POW to survive the war. Taking risks is part of the entrepreneur’s path and the more you develop the ability to be comfortable with being uncomfortable, the greater your long-term rewards will be in your life.

3. Failure is a huge part of the journey.Never let your failures define you or you’ve lost the game. Zamperini was shaping up to be a total failure as a kid. He was getting in fights, drinking by age eight, robbing strangers and neighbors alike and in pretty much every other way misbehaving. By the time he was a teen his parents knew the local police very well. That’s not what you’d call a model start, but with the right support from others and initiative from himself, Zamperini turned things around. It would’ve been easy to give up and define Zamperini as a failure, a lost cause and a bad bet.

Where are you in your entrepreneurial journey? Don’t let others cast the die and define your success. Never let failure define you. You can always find the right support and you can always, always take the initiative to keep improving. An entrepreneur’s path is never straightforward, simple or easy. Embrace the failures you’ve faced and keep moving forward.

Related: 7 Entrepreneurial Lessons a 'Happy Days' Star Learned From an Unlikely Mentor

4. The right support makes all the difference.Speaking of support, it’s debatable whether Zamperini would’ve reached his Olympic success without the support of the right mentors. It wasn’t just his parents that didn’t give up on him during his misspent youth, but his brother, the school’s track coach and even the police became active mentors in coaching Zamperini into a different path that eventually led him to the Olympics.

Surrounding yourself with the right people who believe in you, support you and will rally for you when you’re off track will get you far as an entrepreneur. Likewise, remember that you can give that support and encouragement to other entrepreneurs and up-and-comers in your startup communities.

When Zamperini was stranded in a life raft with the two other survivors of the crashed flight, and later in the barracks of the POW camp, he would talk about his mother’s cooking and other fond memories to improve morale. He actively lent support to the men to keep spirits high.

We all need people to believe in us to help us achieve our best. So get yourself in the right supportive environment and lend a hand to those in need of your mentoring as well.

5. Never give up.Zamperini didn’t just embody the message of never giving up, he literally wrote the book on it. At 97 years old he published and co-authored the book, Don’t Give Up, Don’t Give In: Lessons From An Extraordinary Life. If anyone is qualified to give you advice, wisdom and insights into the indomitable spirit you’ll need in entrepreneurship and in life, it’s Zamperini.

Louis "Louie" Silvie Zamperini

Character Analysis

Catch Him If You Can

Louie is the hero/protagonist of the story.

Louie Zamparini is the guy who almost breaks the four-minute mile, gets swept up by World War II, shot down in the Pacific, punches sharks in the face, survives numerous POW camps, lives, goes home, marries, and finds God. Through it all, he remains… say it with us… unbroken.

We spend a lot of time with Louie as a young boy, before the war starts. He's resourceful and fast-thinking, and he grew up in Torrance, California, just like Dirk Diggler. The childhood scenes—and the fact that most of Louie's childhood stories end with "and then I ran like mad" (1.1.17)—serve to show us how tenacious he is. The kid who never gives up grows into a man who can push through anything.

Even without the war stuff, Louie goes through quite the transformation in his boyhood. Like Spike in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Louie goes from "his hometown's resident archvillain [to] superstar" (1.3.3), and like Robert Downey, Jr., he is sometimes called "Iron Man" (1.3.3). He's also called the "Torrance Tempest" and the "Torrance Tornado," and he's the "youngest distance runner to ever make the team" (1.3.33) in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, He even gets to meet Hitler, who calls him "the boy with the fast finish" (1.4.27).

(We realize getting a compliment from Hitler is like a memoirist getting a blurb from James Frey, but it's neat how Louie plays a Forrest Gump-like role in world history before the war.)

Fear of Flying

When Louie is young, "He wanted nothing to do with airplanes" (1.1.22)—which is a sure sign that he will have something to do with airplanes. Sure enough, despite being "jittery and dogged by airsickness" (1.5.23), Louie is made a bombardier. In other words, he's the guy who drops the bombs and gets to shout the classic phrase bombs away.

Louie is skilled at hitting his targets and playing pranks on his friends during down time, like when he clogs a crewmate's "piss pipe" (2.7.10) with a wad of chewing gum.

Remember the resourcefulness we talked about? Well, it doesn't just come in handy for pulling pranks. During one close landing in the Super Man, Louie manages to splice cables together, tie all the men down, tend to wounds, and ready a parachute, all as their plane is practically flying upside down. It's too bad that the Green Hornet isn't as resilient as Louie is.

Lost at Sea

Louie's perseverance and resourcefulness shine when the Green Hornet goes down. Adrift on a raft with Mac and Phil, the only other surviving crewmen, Louie manages to keep them all alive. He kills an albatross and makes it into bait; he fashions Wolverine-like claws out of fishhooks; and he doesn't resort to cannibalism, even if Mac does start looking like a McDonald's dinner.

Unfortunately though, he can't keep Mac alive, and Louie has a harrowing near-death experience of his own. By harrowing we mean kind of nice: "He saw human figures, silhouetted against the sky. He counted twenty-one of them" (3.16.45). They are singing, and Louie swears he's not hallucinating, even though Phil doesn't hear or see them. Louie will hear them again later in the first POW camp he is imprisoned in, and this vision plays a part in his acceptance of Christianity after returning from the war.

Radio Found the WWII Star

Other places perseverance and resourcefulness come in handy: high school, Survivor, Japanese POW camps. After forty-six days at sea, Louie and Phil are rescued. Well, we should really say captured, because the two men are shipped to a POW camp, the first of several they will be shuffled between over the next two years.

The conditions are pretty terrible (see our analysis of suffering in the "Themes" section for a taste), and to make matters worse, Louie is dogged by Mutsuhiro Watanabe, a sadistic corporal who makes the Marquis de Sade look like a fun-loving Ellen DeGeneres. The Bird does all he can to break Louie, but Louie remains—all together now--unbroken.

Louie's strong morals shine through, even at his lowest moments. When Louie is able to send his family a message on Radio Tokyo, it validates their hopes that he's still alive. But when the radio men try to strike a bargain with Louie by offering to feed him if he'll read messages they wrote, he refuses to be a propaganda tool.

Dead Man Limping

Louie survives two years of being in various POW camps, even though everyone else thinks he's dead. He's even told "Zamperini's dead" (4.33.11) at a clinic and has to prove his identity with the contents of his wallet. He quickly returns to what he knows best: being a WWII-era Ashton Kutcher and punking a track and field recruiter who thought he was dead.

Although Louie is thrilled to be alive and home, he has no direction in life. He injures his ankle and knee doing manual labor for the Bird, and thinks, "I'll never run again" (4.33.23), so after the war, Louie's lost and… well, we almost said broken, but from the title we know that he's not broken. But he's close. Cracked. Almost shattered. Think of some more synonyms for us, guys.

The term PTSD didn't exist in the 1940s, but that's what Louie is going through. He sees the Bird "lurking in his dreams" (5.34.16) and plots ways to exact his revenge against him. Ironically, this obsession merely keeps Louie feeling like a victim of torment: "The paradox of human vengefulness is that it makes men dependent upon those who have harmed them, believing that their release from pain will come only when they make their tormentors suffer" (5.37.16). In other words, hatred hurts the person who holds it in their heart.

Eventually, Louie gets married, has a child, finds God through Billy Graham, and realizes "I am a good man" (5.38.25). He has been drinking heavily for years at this point, but he dumps it all out on the evening he prays in Billy Graham's tent. Later Louie returns to Japan and forgives the men who abused him, even the Bird, with "a radiant smile on his face" (5.39.18). Yup—this dude is definitely unbroken.

Louis "Louie" Silvie Zamperini Timeline & Summary

Russell Allen "Phil" Phillips

Character Analysis

Pilot to Bombardier… Pilot to Bombardier

Phil is like the Ginger Rogers to Louie's Fred Astaire. He has to go through everything Louie does (being shot at, lost at sea for forty-six days, imprisoned in Japanese POW camps) but backwards and in heels.Okay, no heels, but he is the pilot of both the Super Man and the Green Hornet, and he feels a lot of guilt for being at the wheel (or whatever a plane has) when the Green Hornet goes down into the Pacific.

Phil has a less than illustrious beginning to his military career. He was small, short-legged, and his ROTC captain called him "the most unfit, lousy-looking soldier" (2.6.16) he had ever seen. But he quickly proves everyone wrong when he lands the Super Man after it is riddled with 594 bullet holes, and even though the Green Hornet makes a devastating splash down, he survives, along with Louie and Mac.

On the raft, Phil is mostly incapacitated, having been injured in the crash. But he participates in Louie's quiz show antics to keep their minds active. Keeping mentally active probably keeps Phil alive. He experiences so much guilt, he almost feeds himself to sharks: "There were times when Phil seemed lost in trouble thoughts, and Louie guessed that he was reliving the crash, and perhaps holding himself responsible for the deaths of his men" (3.14.29). It's a heavy burden, to say the very least.

The Other Man

Phil's a deeply religious man, and he spends his time singing hymns over the ocean. Maybe Louie absorbs some of Phil's spirituality subconsciously. Phil also pines for his fiancée, Cecile "Cecy" Perry. For her part, Cecy has a fateful experience right out of movie: She goes to a fortune-teller when she learns of Phil's disappearance, where she's told that he will be found before Christmas—a prediction which turns out to be true. They're finally married when Phil returns home from the war.

When Louie and Phil finally wash ashore, they get captured by the Japanese and shuffled from POW camp to POW camp. We lose track of Phil when he isn't suffering the same indignities that Louie is at the hands of the Japanese.

Phil calls himself Allen once again after returning from the war, and seems content enough being "that guy who was with Louie during the war." There is an event in his honor shortly before he dies, finally granting him a deserved moment in the spotlight.

Russell Allen "Phil" Phillips Timeline & Summary

Character Analysis

Bird of Prey

Mutsuhiro Watanabe is a man of many names… and personalities. Known to his family as "Mu-cchan" (4.23.15), to everyone else as the Bird (and a lot of things we can't print here, we're sure), and even sometimes mistranslated as Matsuhiro, Watanabe is the worst of the worst when it comes to abusive prison guards. He makes the creepy guard from The Green Mile seem like a guy you'd love to bring home to dinner.

The Bird gets a few snippets of glowing praise from both Japanese guards and American POWs, like "He did enjoy hurting POWs. […] He was satisfying his sexual desire by hurting them" (4.23.29), and "He was absolutely the most sadistic man I ever met" (4.23.31). Okay, those are more like superlatives than praise, but this bird is more like a vicious hawk than a cute little blue jay, so it only makes sense. In fact, he earns his nickname—the Bird—because it carries "no negative connotation" (4.24.2). Everyone is that afraid of getting on his bad side.

Speaking of his bad side, the Bird is confusingly nice at times, which almost makes him worse. In the middle of beating Louie, he once stops and speaks to him kindly. Louie even thinks, "There was compassion in this man" (4.25.24)… before he gets cracked in the head with a belt buckle again. Forget the Bird's bad side—you don't want to get on any of his sides.

Louie is relieved when the Bird gets kicked out of the Omori prison camp, ordered to leave by Prince Yoshitomo Tokugawa. But Louie's relief is short-lived, and when he arrives at Naoetsu, he's greeted by the Bird. He just can't get away from this dude. (Talk about an albatross… be sure to check out the "Symbols" section for more on this)

Fed up with the abusive treatment, the POWs try to kill the Bird by spiking his food with contaminated stool. He's violently ill, but recovers within two weeks and "take[s] out his rage on the officers and Louie" (4.29.13). It's fun while it lasts (for everyone but the Bird). but his anger is worse than his diarrhea, and when he recovers he makes Louie clean a pig sty with his bare hands, hold a beam for over half an hour, get punched in the face over two hundred times, and threatens to drown him and kill him. He's um… back with a vengeance.

And in short, he's Louie's worst nightmare.

Bird on the Lam

Watanabe vanishes after the atomic bombs are dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and hides around the Japanese countryside for seven years. He either manages to fake his death, or simply gets lucky that a man who looks just like him commits suicide by jumping off a mountain—he only emerges once the arrest order for war criminals is lifted. He manages to live a nice life after that, proving that real life, unlike fiction, is never fair.

When CBS news uncovers Watanabe's story, he agrees to be interviewed. He seems apologetic in one interview, saying that "war is a crime against humanity" (Epilogue.50), but he doesn't believe he is guilty of any wrongdoing, and in fact says that "beating and kicking were unavoidable" (Epilogue.70) in certain situations. Yikes.

To atone for whatever wrong he thinks he did, he offers to let any of the men he hurt come to Japan and hit him. Hmm, maybe his sexual tastes have changed in old age. No one takes him up on the offer, though, and when Louie tries to meet the Bird, the Bird refuses to meet him. He's flown the coop for good, and no one sees him again.

Mutsuhiro Watanabe a.k.a. the Bird Timeline & Summary

Character Analysis

All that Glitters

If Unbroken were a novel, Cynthia would be a character who came out of nowhere. She appears in the book's final part, and ends up being the love of Louie's life. He sees Cynthia at a bar shortly after returning home from the war. She has a "shimmer about her, an incandescence" (5.33.33), and when Louie sees her, he has the astounding thought that he has to marry her.

And he does.

It's not a happily ever after for either person, though. Cynthia is Louie's opposite, writing novels, painting, and yearning to see the world. Louie has already seen the world though, and while she's pretty well off, Louie is poor. Her parents don't want her to marry Louie, but the lovebirds do anyway on the sly.

Unfortunately, Cynthia doesn't understand Louie's drinking problem, which is getting worse every day do to the PTSD he suffers and his nightmares of the Bird. She's not quite sleeping with the enemy, like Julia Roberts, but "she was engaged to a stranger" (5.33.41). It's a major bummer.

Cynthia almost leaves Louie because he won't stop drinking, and she files for divorce after having a baby, little Cynthia, and coming home to find Louie shaking her. But it's thanks to Cynthia that Louie turns his life around. She convinces him to go see Billy Graham, the preacher, not once, but twice. If she hadn't done that, Louie might not have found the peace within himself, and the ability to forgive those who had wronged him during the war.

Francis "Mac" McNamara

Character Analysis

He's Come Undone

We lose a lot of crewman when the Green Hornet goes down, but watching Mac's slow decline into madness might be the most difficult death to watch.

Along with Louie and Phil, Mac survives the crash into the Pacific, but it's all downhill from there. First, he eats all the survival chocolate, eliminating days' worth of rations in a few seconds. Even though Louie understands that Mac did this in a moment of panic, he's still not happy about it.

In a life or death situation, it's important that everyone keep their cool, and Mac does not keep his cool. He starts screaming "We're going to die!" (3.12.17), and although Mac stands up (literally) at one point and whacks a shark with an oar—saving Louie—he soon returns to his near vegetative state. Eventually he dies, and Louie and Phil wrap him in part of the raft and drop him into the water. "Mac sank away. The sharks let him be" (3.16.31). And that's the end of Mac.

Crew of the Super Man

Character Analysis

Justice League

Other than their names and their positions, we don't get to learn too much about the personalities or private lives of the crewmen of the Super Man. Most likely, these omissions are to keep the story focused on Louie. Or maybe it's because it would just be too difficult to read about the fates of these men if we knew more about them.

Here's the roll call: Stanley Pillsbury, the top gunner; Clarence Douglas, waist gunner; Robert Mitchell, navigator; Frank Glassman, the radioman who looks like Harpo Marx; Ray Lambert, tail gunner; Harry Brooks, another waist gunner, and George Moznette, Jr., copilot, who is soon replaced by Charleton Hugh Cuppernell.

We get more characterization about the plane than we do the men. They name their plane Super Man, which is step-up from the common nickname "the Constipated Lumberer" (2.6.27) or worse, "The Flying Coffin" (2.6.32). These nicknames serve to make the survival of the plane, after getting shot at more than five hundred times, all the more miraculous. The fact that they don't all die is due to a near-magical combination of Phil's mad pilot skills and the hardy constitution of the plane.

The Zamperini Family

Character Analysis

Family Matters

Louie's family always supports him, from the time he's a trouble teenager, to when he's a track superstar, and, finally when he's a decorated war hero. His father, Anthony, was a coal miner, boxer, and construction worker, and his mom, Louise, is a housewife who had Louie when she was eighteen. They do not come from illustrious beginnings, and the Zamperinis lived in a one-room shack for a year—with no running water—that Louise defended with a rolling pin.

That's just one of the ways we're shown that Louise is crafty and scrappy, just like her son. She even gets into a fight with four kids who try to steal her pants and later bribes one of Louie's schoolmates to spy on him. In other words, this mom wouldn't seem out of place in your average network primetime sitcom.

Throughout Unbroken, we get glimpses of what the Zamperinis are up to while Louie is lost at sea and imprisoned. They too are unbroken, never losing faith that their son is still alive. Even though Louise develops a rash when she learns of Louie's disappearance, she never believes that her son is dead. Sylvia, Louie's sister, takes his disappearance hard too—she is often "wracked with anxiety" and "barely able to eat" (4.21.9), but she also believes in her brother's strength and ingenuity.

Louie loves his whole family, but he is perhaps closest to his brother, Pete. Pete is "everything [Louie] was not" (1.1.23) when the boys are younger, and it's Pete's strong influence that changes Louie's life. Pete convinces Louie to try his hand (well, his feet) at athletics, and he always believes in his brother, even trying to get him to break the four-minute mile.

If Louie didn't have such a strong family unit, we wouldn't have Unbroken. Laura Hillenbrand seems to have relied just as much on their memories and mementos (like Pete's giant Louie-related scrapbook) to weave together Louie's tale, so not only do they hold Louie up throughout his life, but they also help make this book possible.

Kunichi James "Jimmie" Sasaki

Character Analysis

International Man of Mystery

Jimmie Sasaki remains a mystery from the beginning of the book up until the end. When we meet him, he's a track fan attending college with Louie. He spends his time convincing people to send money to Japan to help the poor, but what he's really funding is Japan's war efforts against America with American money.

It turns out that he's a fake student, 21 Jump Street-style. He's almost forty and under FBI investigation. Ha.

When Jimmie resurfaces in Yokohama, he literally says to Louie, "We meet again" (4.19.16), officially making himself a character from a cheesy spy movie. Louie goes back and forth between believing that Sasaki is watching after him and believing that Sasaki doesn't give a flying maki roll about him. No one knows where this dude's loyalties lie, though at one point, "he began to sound like he was rooting for the Allies" (4.22.16). But really—no one's ever sure.

After the war, Jimmie is sentenced to six years in Sugamo Prison, where he tends his own vegetable garden. Whether he was an "artful spy" (5.35.15) or not remains unknown.

Other Men

Character Analysis

POWs

Louie meets a variety of men as he's carted from POW camp to the next. Some he inspires, and some inspire him to hold on and survive. One man who tells us a lot about the search for Louie is Joe Deasy. He piloted the Daisy Mae, a search plane, and even though he never found the crew of the Green Hornet, he was always on the look out for them.

In Ofuna, Louie meets William Harris, a marine with a photographic memory. Harris is beaten to a pulp by the Quack and never quite recovers his memory. Harris is eventually transferred to Omori, and although he's on death's doorstep when he arrives, he manages to recover. He stays in the Marines and disappears in the 1950s in Korea.

There's also one-legged Fred Garrett, who was once put in the cell where Louie carved his name. Later on they end up in the same hospital in Honolulu after the war ends, and they reunite at a restaurant two years after this. Fred has a prosthetic leg and freaks out over a plate of rice, a moment of post-traumatic stress from his years in the Japanese POW camps with only rice to eat.

Finally, there's Frank Tinker, a dive-bomber pilot and opera singer (4.20.36). Louie and Tinker plot to escape Ofuna, but their plan never comes to fruition.

Good Cop, Bad Cop

There are both good guards in the Japanese POW camps and bad ones. You can tell the bad ones by their nicknames—like the Quack, the Weasel, and, of course, Shithead. (That's Mr. Shithead to most of you.)

Also known as "The Butcher," the Quack is the most hated official in Ofuna. He tortures and mutilates captives (like William Harris, who we mentioned above) "while quizzing them on their pain" (4.19.35). When the men steal a map from the Quack, he beats Bill Harris until Bill is disfigured and cannot recognize his friends. After the war, the Quack is sentenced to hang.

Louie gives the Weasel a "coquettish" (4.22.7) eyebrow trim à la Marlene Dietrich, but somehow manages to escape retribution for the prank. And the guard known as Shithead violates Gaga the duck and kills him. These are not nice men, in case you couldn't guess.

Not all the Japanese Louie meets are bad, however. A guard known as Kawamura draws pictures of cars, planes, ice cream, and the like, writing the Japanese names for them to help the POWs learn to communicate. He even takes revenge on guards who hurt Louie. Hirose has captives fake screaming so it only seems like he beat them, and Kano once "snuck sick man from the sadistic Japanese doctor and into the hands of a POW who was a physician" (4.24.27). Yup—they're not all bad just because they're POW guards.

Even though Kano is relatively kind, he gets sentenced to jail for a time, being confused for Hiroaki Kono, a man described as a "roaring Hitlerian animal" (4.28.8). After Kano's release, he hesitates to contact his POW friends for fear of reminding them of terrible times.

These men prove that just because war causes people to do bad things, not all people succumb to the pressure to be evil. Perhaps it is only the ones who are already evil at heart.

Unbroken Questions

Young Louie Zamperini is the troublemaker of Torrance, California, stealing food, running like hell, and dreaming of hopping on a train and leaving town for good. His beloved older brother, Pete, manages to turn his life around, though, translating Louie's love of running from the law into a passion for track and field. Louie breaks high school records, goes to the Olympic Games in Berlin in 1936, and trains to beat the four-minute-mile.

His running career is put on hold when the Second World War breaks out. Louie enlists in the army air corps and becomes a bombardier. He and his crew, including pilot "Phil" Phillips, have a harrowing air battle in their plane, the Super Man. But Phil's pilot skills and Louie's ingenuity enables them to land the plane, even though it's riddled with over five hundred bullet holes.

With the Super Man succumbed to its kryptonite, the men are transferred to the Green Hornet—a less-reliable plane, the Hornet is shot down over the Pacific. Only three men survive: Louie, Phil, and Mac. Phil wrestles with his guilt about crashing, Mac kind of goes nuts, and Louie wrestles a shark from the ocean with his bare hands and eats its liver. (We are not making that up.) Unfortunately, Mac dies at sea.

Louie and Phil survive for forty-six days, but only to be captured by the Japanese and holed away in a terrible POW camp. The men are shuffled from camp to camp, each one almost worse than the last, until the war ends. Louie survives, despite being pursued by a sadistic guard nicknamed the Bird, punched over two hundred times, and forced to clean a pigsty with his bare hands.

Back home, Louie reunites with his family and marries his love-at-first-sight: Cynthia. They have a daughter and, well, a drinking problem. Louie is haunted by the horrors of war and turns to alcohol to forget. He is directionless, unable to run or find a new career; he dreams of going to Japan and killing the Bird. The newlyweds' life reaches a low point when Cynthia catches Louie shaking the baby. She files for divorce.

Cynthia changes her mind when Billy Graham (yes, the Billy Graham) comes to town. She manages to convince Louie to attend one of his tent preaching sessions. Louie remembers a bargain he made with God while on the raft, and the relative peace he felt that day at sea. Finding faith enables him to quit drinking and become a motivational speaker.

Years later, Louie forgives all the men who wronged him during the war. When it turns out that the Bird is still alive, Louie hopes to meet the man and forgive him in person—the Bird refuses, but Louie sends him a letter. In 1998, Louie carries the Olympic torch past Naoetsu, where he was once imprisoned, and he puts his dark past behind him.

How It All Goes Down

How It All Goes Down

The One-Boy Insurgency

How It All Goes Down

Run Like Mad

How It All Goes Down

The Torrance Tornado

How It All Goes Down

Plundering Germany

How It All Goes Down

Into War

How It All Goes Down

The Flying Coffin

How It All Goes Down

"This Is It, Boys"