http://www.canadianshakespeares.ca/folio/Sources/romeusandjuliet.pdf

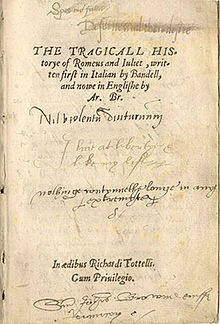

The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet is a narrative poem, first published in 1562 by Arthur Brooke, which was the key source for William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Brooke is reported to have translated it from an Italian novella by Matteo Bandello; by another theory, it is mainly derived from a French version which involves a man by the name of Reomeo Titensus and Juliet Bibleotet by Pierre Boaistuau, published by Richard Tottell.

Little is known about Arthur Brooke. He was admitted as a member of Inner Temple on 18 December 1561 under the sponsorship of Thomas Sackville and Thomas Norton.[1] He drowned in 1563 by shipwreck while crossing to help Protestant forces in the French Wars of Religion.

The poem's ending differs significantly from Shakespeare's play—the nurse is banished and the apothecary is hanged for their involvement in the deception, while Friar Lawrence leaves Verona to live in a hermitage until he dies.

Little is known about Arthur Brooke. He was admitted as a member of Inner Temple on 18 December 1561 under the sponsorship of Thomas Sackville and Thomas Norton.[1] He drowned in 1563 by shipwreck while crossing to help Protestant forces in the French Wars of Religion.

The poem's ending differs significantly from Shakespeare's play—the nurse is banished and the apothecary is hanged for their involvement in the deception, while Friar Lawrence leaves Verona to live in a hermitage until he dies.

The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet is a narrative poem, first published in 1562 by Arthur Brooke, which was the key source for William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Brooke is reported to have translated it from an Italian novella by Matteo Bandello; by another theory, it is mainly derived from a French version which involves a man by the name of Reomeo Titensus and Juliet Bibleotet by Pierre Boaistuau, published by Richard Tottell.

Little is known about Arthur Brooke. He was admitted as a member of Inner Temple on 18 December 1561 under the sponsorship of Thomas Sackville and Thomas Norton.[1] He drowned in 1563 by shipwreck while crossing to help Protestant forces in the French Wars of Religion.

The poem's ending differs significantly from Shakespeare's play—the nurse is banished and the apothecary is hanged for their involvement in the deception, while Friar Lawrence leaves Verona to live in a hermitage until he dies.

Little is known about Arthur Brooke. He was admitted as a member of Inner Temple on 18 December 1561 under the sponsorship of Thomas Sackville and Thomas Norton.[1] He drowned in 1563 by shipwreck while crossing to help Protestant forces in the French Wars of Religion.

The poem's ending differs significantly from Shakespeare's play—the nurse is banished and the apothecary is hanged for their involvement in the deception, while Friar Lawrence leaves Verona to live in a hermitage until he dies.

Shakespeare's Characters: Romeo (Romeo and Juliet) Romeo, the hero of Romeo and Juliet, is in love with Rosaline at the beginning of the play. He soon falls in love with and marries Juliet (2.6). The Prince banishes him from Verona for killing Tybalt (3.1), and he flees to Mantua (3.3) where he slays Paris and dies along side Juliet (5.3).

No one has summarized Romeo’s character better than the 19th-century scholar, Dr. Maginn: Lightning, flame, shot, explosion, are the favourite parallels to the conduct and career of Romeo. Swift are his loves; as swift to enter his thought, the mischief which ends them forever. Rapid have been all the pulsations of his life; as rapid, the determination which decides that they shall beat no more. A gentleman he was in heart and soul. All his habitual companions love him: Benvolio and Mercutio, who represent the young gentlemen of his house, are ready to peril their lives, and to strain all their energies, serious or gay, in his service. His father is filled with an anxiety on his account so delicate, that he will not venture to interfere with his son’s private sorrows while he desires to discover their source, and if possible to relieve them. The heart of his mother bursts in his calamity; the head of the rival house bestows upon him the warmest panegyrics; the tutor of his youth sacrifices everything to gratify his wishes; his servant, though no man is a hero to his valet de chambre, dares not remonstrate with him on his intentions, even when they are avowed to be savage-wild,

More fierce, and more inexorable far,

Than empty tigers or the roaring sea

but with an eager solicitude he breaks his commands by remaining as close as he can venture, to watch over his safety. Kind he is to all. He wins the heart of the romantic Juliet by his tender gallantry: the worldly-minded nurse praises him for being as gentle as a lamb.

When it is necessary or natural that the Prince or Lady Montague should speak harshly of him, it is done in his absence. No words of anger or reproach are addressed to his ears save by Tybalt; and from him they are in some sort a compliment, as signifying that the self-chosen prize fighter of the opposing party deems Romeo the worthiest antagonist of his blade (from The Shakespeare Papers, quoted in Bentley's Miscellany, 66).

No one has summarized Romeo’s character better than the 19th-century scholar, Dr. Maginn: Lightning, flame, shot, explosion, are the favourite parallels to the conduct and career of Romeo. Swift are his loves; as swift to enter his thought, the mischief which ends them forever. Rapid have been all the pulsations of his life; as rapid, the determination which decides that they shall beat no more. A gentleman he was in heart and soul. All his habitual companions love him: Benvolio and Mercutio, who represent the young gentlemen of his house, are ready to peril their lives, and to strain all their energies, serious or gay, in his service. His father is filled with an anxiety on his account so delicate, that he will not venture to interfere with his son’s private sorrows while he desires to discover their source, and if possible to relieve them. The heart of his mother bursts in his calamity; the head of the rival house bestows upon him the warmest panegyrics; the tutor of his youth sacrifices everything to gratify his wishes; his servant, though no man is a hero to his valet de chambre, dares not remonstrate with him on his intentions, even when they are avowed to be savage-wild,

More fierce, and more inexorable far,

Than empty tigers or the roaring sea

but with an eager solicitude he breaks his commands by remaining as close as he can venture, to watch over his safety. Kind he is to all. He wins the heart of the romantic Juliet by his tender gallantry: the worldly-minded nurse praises him for being as gentle as a lamb.

When it is necessary or natural that the Prince or Lady Montague should speak harshly of him, it is done in his absence. No words of anger or reproach are addressed to his ears save by Tybalt; and from him they are in some sort a compliment, as signifying that the self-chosen prize fighter of the opposing party deems Romeo the worthiest antagonist of his blade (from The Shakespeare Papers, quoted in Bentley's Miscellany, 66).

Shakespeare's Characters: Juliet (Romeo and Juliet) We first see Juliet, the heroine of Romeo and Juliet, in 1.3., with her mother, Lady Capulet and the Nurse. She meets Romeo in 1.5. and they are married in 1.6. Juliet stabs herself in 5.3.

From The Works of William Shakespeare. Vol. 8. Ed. Evangeline Maria O'Connor. J.D. Morris and Co.

Such is the simplicity, the truth, and the loveliness of Juliet's character, that we are not at first aware of its complexity, its depth, and its variety. There is in it an intensity of passion, a singleness of purpose, an entireness, a completeness of effect, which we feel as a whole; and to attempt to analyze the impression thus conveyed at once to soul and sense, is as if while hanging over a half-blown rose, and revelling in its intoxicating perfume, we should pull it asunder, leaflet by leaflet, the better to display its bloom and fragrance.

. . . All Shakspeare's women, being essentially women, either love or have loved, or are capable of loving; but Juliet is love itself. The passion is her state of being, and out of it she has no existence. It is the soul within her soul; the pulse within her heart; the life-blood along her veins, "blending with every atom of her frame." The love that is so chaste and dignified in Portia — so airy-delicate and fearless in Miranda — so sweetly confiding in Perdita — so playfully fond in Rosalind — so constant in Imogen — so devoted in Desdemona — so fervent in Helen — so tender in Viola — is each and all of these in Juliet.

In the delineation of that sentiment which forms the groundwork of the drama, nothing in fact can equal the power of the picture but its inexpressible sweetness and its perfect grace: the passion which has taken possession of Juliet's whole soul has the force, the rapidity, the resistless violence of the torrent; but she is herself as "moving delicate," as fair, as soft, as flexible as the willow that bends over it, whose light leaves tremble even with the motion of the current which hurries beneath them. But at the same time that the pervading sentiment is never lost sight of, and is one and the same throughout, the individual part of the character in all its variety is developed, and marked with the nicest discrimination. For instance, the simplicity of Juliet is very different from the simplicity of Miranda; her innocence is not the innocence of a desert island. The energy she displays does not once remind us of the moral grandeur of Isabel, or the intellectual power of Portia; it is founded in the strength of passion, not in the strength of character; it is accidental rather than inherent, rising with the tide of feeling or temper, and with it subsiding. Her romance is not the pastoral romance of Perdita, nor the fanciful romance of Viola; it is the romance of a tender heart and a poetical imagination. Her inexperience is not ignorance; she has heard that there is such a thing as falsehood, though she can scarcely conceive it. Her mother and her nurse have perhaps warned her against flattering vows and man's inconstancy. . . . Our impression of Juliet's loveliness and sensibility is enhanced, when we find it overcoming in the bosom of Romeo a previous love for another. His visionary passion for the cold, inaccessible Rosaline, forms but the prologue, the threshold, to the true, the real sentiment which succeeds to it. This incident, which is found in the original story, has been retained by Shakspeare with equal feeling and judgement; and far from being a fault in taste and sentiment, far from prejudicing us against Romeo, by casting on him, at the outset of the piece, the stigma of inconstancy, it becomes, if properly considered, a beauty in the drama, and adds a fresh stroke of truth to the portrait of the lover. Why, after all, should we be offended at what does not offend Juliet herself? for in the original story we find that her attention is first attracted towards Romeo, by seeing him "fancy-sick and pale of cheer, for love of a cold beauty. . . ."

In the extreme vivacity of her imagination, and its influence upon the action, the language, the sentiments of the drama, Juliet resembles Portia; but with this striking difference. In Portia, the imaginative power, though developed in a high degree, is so equally blended with the other intellectual and moral faculties, that it does not give us the idea of excess. It is subject to her nobler reason; it adorns and heightens all her feelings; it does not overwhelm or mislead them. In Juliet, it is rather a part of her southern temperament, controlling and modifying the rest of her character; springing from her sensibility, hurried along by her passions, animating her joys, darkening her sorrows, exaggerating her terrors, and, in the end, overpowering her reason. With Juliet, imagination is, in the first instance, if not the source, the medium of passion; and passion again kindles her imagination.

It is through the power of imagination that the eloquence of Juliet is so vividly poetical; that every feeling, every sentiment comes to her clothed in the richest imagery, and is thus reflected from her mind to ours. The poetry is not here the mere adornment, the outward garnishing of the character; but its result, or rather blended with its essence. It is indivisible from it, and interfused through it like moonlight through the summer air. To particularize is almost impossible, since the whole of the dialogue appropriated to Juliet is one rich stream of imagery. . . .

The famous soliloquy, "Gallop apace, ye fiery-footed steeds," teems with luxuriant imagery. The fond adjuration, "Come night I come Romeo! come thou day in night!" expresses that fulness of enthusiastic admiration for her lover, which possesses her whole soul; but expresses it as only Juliet could or would have expressed it — in a bold and beautiful metaphor. Let it be remembered that in this speech Juliet is not supposed to be addressing an audience, nor even a confidante; and I confess I have been shocked at the utter want of taste and refinement in those who, with coarse derision, or in a spirit of prudery, yet more gross and perverse, have dared to comment on this beautiful "Hymn to the Night," breathed out by Juliet in the silence and solitude of her chamber. She is thinking aloud; it is the young heart "triumphing to itself in words." In the midst of all the vehemence with which she calls upon the night to bring Romeo to her arms, there is something so almost infantine in her perfect simplicity, so playful and fantastic in the imagery and language, that the charm of sentiment and innocence is thrown over the whole; and her impatience, to use her own expression, is truly that of "a child before a festival, that hath new robes and may not wear them." It is at the very moment too that her whole heart and fancy are abandoned to blissful anticipation, that the nurse enters with the news of Romeo's banishment; and the immediate transition from rapture to despair has a most powerful effect. . . .

It is in truth a tale of love and sorrow, not of anguish and terror. We behold the catastrophe afar off with scarcely a wish to avert it. Romeo and Juliet must die; their destiny is fulfilled; they have quaffed off the cup of life, with all its infinite of joys and agonies, in one intoxicating draught. What have they to do more upon this earth? Young, innocent, loving and beloved, they descend together into the tomb; but Shakspeare has made that tomb a shrine of martyred and sainted affection consecrated for the worship of all hearts — not a dark charnel vault, haunted by spectres of pain, rage, and desperation. Romeo and Juliet are pictured lovely in death as in life; the sympathy they inspire does not oppress us with that suffocating sense of horror which in the altered tragedy makes the fall of the curtain a relief; but all pain is lost in the tenderness and poetic beauty of the picture.

From The Works of William Shakespeare. Vol. 8. Ed. Evangeline Maria O'Connor. J.D. Morris and Co.

Such is the simplicity, the truth, and the loveliness of Juliet's character, that we are not at first aware of its complexity, its depth, and its variety. There is in it an intensity of passion, a singleness of purpose, an entireness, a completeness of effect, which we feel as a whole; and to attempt to analyze the impression thus conveyed at once to soul and sense, is as if while hanging over a half-blown rose, and revelling in its intoxicating perfume, we should pull it asunder, leaflet by leaflet, the better to display its bloom and fragrance.

. . . All Shakspeare's women, being essentially women, either love or have loved, or are capable of loving; but Juliet is love itself. The passion is her state of being, and out of it she has no existence. It is the soul within her soul; the pulse within her heart; the life-blood along her veins, "blending with every atom of her frame." The love that is so chaste and dignified in Portia — so airy-delicate and fearless in Miranda — so sweetly confiding in Perdita — so playfully fond in Rosalind — so constant in Imogen — so devoted in Desdemona — so fervent in Helen — so tender in Viola — is each and all of these in Juliet.

In the delineation of that sentiment which forms the groundwork of the drama, nothing in fact can equal the power of the picture but its inexpressible sweetness and its perfect grace: the passion which has taken possession of Juliet's whole soul has the force, the rapidity, the resistless violence of the torrent; but she is herself as "moving delicate," as fair, as soft, as flexible as the willow that bends over it, whose light leaves tremble even with the motion of the current which hurries beneath them. But at the same time that the pervading sentiment is never lost sight of, and is one and the same throughout, the individual part of the character in all its variety is developed, and marked with the nicest discrimination. For instance, the simplicity of Juliet is very different from the simplicity of Miranda; her innocence is not the innocence of a desert island. The energy she displays does not once remind us of the moral grandeur of Isabel, or the intellectual power of Portia; it is founded in the strength of passion, not in the strength of character; it is accidental rather than inherent, rising with the tide of feeling or temper, and with it subsiding. Her romance is not the pastoral romance of Perdita, nor the fanciful romance of Viola; it is the romance of a tender heart and a poetical imagination. Her inexperience is not ignorance; she has heard that there is such a thing as falsehood, though she can scarcely conceive it. Her mother and her nurse have perhaps warned her against flattering vows and man's inconstancy. . . . Our impression of Juliet's loveliness and sensibility is enhanced, when we find it overcoming in the bosom of Romeo a previous love for another. His visionary passion for the cold, inaccessible Rosaline, forms but the prologue, the threshold, to the true, the real sentiment which succeeds to it. This incident, which is found in the original story, has been retained by Shakspeare with equal feeling and judgement; and far from being a fault in taste and sentiment, far from prejudicing us against Romeo, by casting on him, at the outset of the piece, the stigma of inconstancy, it becomes, if properly considered, a beauty in the drama, and adds a fresh stroke of truth to the portrait of the lover. Why, after all, should we be offended at what does not offend Juliet herself? for in the original story we find that her attention is first attracted towards Romeo, by seeing him "fancy-sick and pale of cheer, for love of a cold beauty. . . ."

In the extreme vivacity of her imagination, and its influence upon the action, the language, the sentiments of the drama, Juliet resembles Portia; but with this striking difference. In Portia, the imaginative power, though developed in a high degree, is so equally blended with the other intellectual and moral faculties, that it does not give us the idea of excess. It is subject to her nobler reason; it adorns and heightens all her feelings; it does not overwhelm or mislead them. In Juliet, it is rather a part of her southern temperament, controlling and modifying the rest of her character; springing from her sensibility, hurried along by her passions, animating her joys, darkening her sorrows, exaggerating her terrors, and, in the end, overpowering her reason. With Juliet, imagination is, in the first instance, if not the source, the medium of passion; and passion again kindles her imagination.

It is through the power of imagination that the eloquence of Juliet is so vividly poetical; that every feeling, every sentiment comes to her clothed in the richest imagery, and is thus reflected from her mind to ours. The poetry is not here the mere adornment, the outward garnishing of the character; but its result, or rather blended with its essence. It is indivisible from it, and interfused through it like moonlight through the summer air. To particularize is almost impossible, since the whole of the dialogue appropriated to Juliet is one rich stream of imagery. . . .

The famous soliloquy, "Gallop apace, ye fiery-footed steeds," teems with luxuriant imagery. The fond adjuration, "Come night I come Romeo! come thou day in night!" expresses that fulness of enthusiastic admiration for her lover, which possesses her whole soul; but expresses it as only Juliet could or would have expressed it — in a bold and beautiful metaphor. Let it be remembered that in this speech Juliet is not supposed to be addressing an audience, nor even a confidante; and I confess I have been shocked at the utter want of taste and refinement in those who, with coarse derision, or in a spirit of prudery, yet more gross and perverse, have dared to comment on this beautiful "Hymn to the Night," breathed out by Juliet in the silence and solitude of her chamber. She is thinking aloud; it is the young heart "triumphing to itself in words." In the midst of all the vehemence with which she calls upon the night to bring Romeo to her arms, there is something so almost infantine in her perfect simplicity, so playful and fantastic in the imagery and language, that the charm of sentiment and innocence is thrown over the whole; and her impatience, to use her own expression, is truly that of "a child before a festival, that hath new robes and may not wear them." It is at the very moment too that her whole heart and fancy are abandoned to blissful anticipation, that the nurse enters with the news of Romeo's banishment; and the immediate transition from rapture to despair has a most powerful effect. . . .

It is in truth a tale of love and sorrow, not of anguish and terror. We behold the catastrophe afar off with scarcely a wish to avert it. Romeo and Juliet must die; their destiny is fulfilled; they have quaffed off the cup of life, with all its infinite of joys and agonies, in one intoxicating draught. What have they to do more upon this earth? Young, innocent, loving and beloved, they descend together into the tomb; but Shakspeare has made that tomb a shrine of martyred and sainted affection consecrated for the worship of all hearts — not a dark charnel vault, haunted by spectres of pain, rage, and desperation. Romeo and Juliet are pictured lovely in death as in life; the sympathy they inspire does not oppress us with that suffocating sense of horror which in the altered tragedy makes the fall of the curtain a relief; but all pain is lost in the tenderness and poetic beauty of the picture.

Shakespeare on Fate We have a Roman scholar named Boethius to thank for the medieval and Renaissance fixation on "fortune's wheel." Queen Elizabeth herself translated his hugely popular discourse on fate's role in the Universe, The Consolation of Philosophy. Although the idea of the wheel of fortune existed before Boethius, his work was the source on the subject for Chaucer, Dante, Machiavelli, and of course, Shakespeare. In the words of Boethius: With domineering hand she moves the turning wheel,

Like currents in a treacherous bay swept to and fro:

Her ruthless will has just deposed once fearful kings

While trustless still, from low she lifts a conquered head;

No cries of misery she hears, no tears she heeds,

But steely hearted laughs at groans her deeds have wrung.

Such is a game she plays, and so she tests her strength;

Of mighty power she makes parade when one short hour

Sees happiness from utter desolation grow.

(A Consolation of Philosophy, Book II, translated by V.E. Watts) Shakespearean Quotations on Fate Please see the plays section for full explanatory notes.

____

Our remedies oft in ourselves do lie,

Which we ascribe to heaven: the fated sky

Gives us free scope, only doth backward pull

Our slow designs when we ourselves are dull.

(All's Well that Ends Well, 1.1.209), Helena

Let us sit and mock the good housewife Fortune from her wheel, that her gifts may henceforth be bestowed equally. (As You Like It, 1.2.30), Celia to Rosalind

Wear this for me, one out of suits with fortune.

(As You Like It, 1.2.224), Rosalind, giving Orlando her necklace.

My fate cries out,

And makes each petty artery in this body

As hardy as the Nemean lion's nerve.

(Hamlet, 1.4.91), Hamlet

[You live] in the secret parts of Fortune?

O, most true; she is a strumpet.

(Hamlet, 2.2.235), Hamlet to Guildenstern

Our wills and fates do so contrary run

That our devices still are overthrown;

Our thoughts are ours, their ends none of our own.

(Hamlet, 3.2.208), Player King

You must sing a-down a-down,

An you call him a-down-a.

O, how the wheel becomes it! It is the false

steward, that stole his master's daughter.

(Hamlet, 4.5.176), Ophelia

There's a special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, 'tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come: the readiness is all: since no man has aught of what he leaves, what is't to leave betimes?

(Hamlet, 5.2.214), Hamlet to Horatio

Giddy Fortune's furious fickle wheel,

That goddess blind,

That stands upon the rolling restless stone.

(Henry V, 3.3.27), Pistol to Fluellen

What fates impose, that men must needs abide;

It boots not to resist both wind and tide.

(3 Henry VI, 4.3.60), King Edward IV to Warwick

O God! that one might read the book of fate,

And see the revolution of the times

Make mountains level, and the continent,

Weary of solid firmness, melt itself

Into the sea! and, other times, to see

The beachy girdle of the ocean

Too wide for Neptune's hips; how chances mock,

And changes fill the cup of alteration

With divers liquors!

(2 Henry IV, 3.1.46), King Henry IV

Men at some time are masters of their fates:

The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars,

But in ourselves, that we are underlings.

(Julius Caesar, 1.2.146), Cassius to Brutus

It is the stars,

The stars above us, govern our conditions.

(King Lear, 4.3.37), Kent

The wheel is come full circle.

(King Lear, 5.3.203), Edmund

The sea will ebb and flow, heaven show his face,

Young blood doth not obey an old decree:

We cannot cross the cause why we were born.

(Love's Labour's Lost, 4.3.203), Biron

That I may pour my spirits in thine ear;

And chastise with the valour of my tongue

All that impedes thee from the golden round,

Which fate and metaphysical aid doth seem

To have thee crown'd withal.

(Macbeth, 1.5.27), Lady Macbeth

I fear too early, for my mind misgives

Some consequence, yet hanging in the stars

Shall bitterly begin his fearful date

With this night's revels, and expire the term

Of a dispised life, clos'd in my breast,

By some vile forfeit of untimely death.

But he that hath the steerage of my course

Direct my sail.

(Romeo and Juliet, 1.4.113), Romeo

O, I am fortune's fool!

(Romeo and Juliet, 3.1.139), Romeo

O God, I have an ill-divining soul!

(Romeo and Juliet, 3.5.55), Juliet. Romeo actually speaks this line in Q2.

O fortune, fortune! all men call thee fickle:

If thou art fickle, what dost thou with him.

That is renown'd for faith? Be fickle, fortune;

For then, I hope, thou wilt not keep him long,

But send him back.

(Romeo and Juliet, 3.5.59-63), Juliet

When in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes

I all alone beweep my outcast state.

(Sonnet 29)

By accident most strange, bountiful Fortune,

Now my dear lady, hath mine enemies

Brought to this shore; and by my prescience

I find my zenith doth depend upon

A most auspicious star, whose influence

If now I court not but omit, my fortunes

Will ever after droop.

(The Tempest, 1.2.209), Prospero to Miranda

The providence that's in a watchful state

Knows almost every grain of Plutus' gold,

Finds bottom in the uncomprehensive deeps,

Keeps place with thought and almost, like the gods,

Does thoughts unveil in their dumb cradles.

There is a mystery--with whom relation

Durst never meddle--in the soul of state;

Which hath an operation more divine

Than breath or pen can give expressure to.

(Troilus and Cressida, 3.3.207), Ulysses to Achilles

My stars shine darkly over

me: the malignancy of my fate might perhaps

distemper yours.

(Twelfth Night, 2.1.3), Sebastian to Antonio)

Like currents in a treacherous bay swept to and fro:

Her ruthless will has just deposed once fearful kings

While trustless still, from low she lifts a conquered head;

No cries of misery she hears, no tears she heeds,

But steely hearted laughs at groans her deeds have wrung.

Such is a game she plays, and so she tests her strength;

Of mighty power she makes parade when one short hour

Sees happiness from utter desolation grow.

(A Consolation of Philosophy, Book II, translated by V.E. Watts) Shakespearean Quotations on Fate Please see the plays section for full explanatory notes.

____

Our remedies oft in ourselves do lie,

Which we ascribe to heaven: the fated sky

Gives us free scope, only doth backward pull

Our slow designs when we ourselves are dull.

(All's Well that Ends Well, 1.1.209), Helena

Let us sit and mock the good housewife Fortune from her wheel, that her gifts may henceforth be bestowed equally. (As You Like It, 1.2.30), Celia to Rosalind

Wear this for me, one out of suits with fortune.

(As You Like It, 1.2.224), Rosalind, giving Orlando her necklace.

My fate cries out,

And makes each petty artery in this body

As hardy as the Nemean lion's nerve.

(Hamlet, 1.4.91), Hamlet

[You live] in the secret parts of Fortune?

O, most true; she is a strumpet.

(Hamlet, 2.2.235), Hamlet to Guildenstern

Our wills and fates do so contrary run

That our devices still are overthrown;

Our thoughts are ours, their ends none of our own.

(Hamlet, 3.2.208), Player King

You must sing a-down a-down,

An you call him a-down-a.

O, how the wheel becomes it! It is the false

steward, that stole his master's daughter.

(Hamlet, 4.5.176), Ophelia

There's a special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, 'tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come: the readiness is all: since no man has aught of what he leaves, what is't to leave betimes?

(Hamlet, 5.2.214), Hamlet to Horatio

Giddy Fortune's furious fickle wheel,

That goddess blind,

That stands upon the rolling restless stone.

(Henry V, 3.3.27), Pistol to Fluellen

What fates impose, that men must needs abide;

It boots not to resist both wind and tide.

(3 Henry VI, 4.3.60), King Edward IV to Warwick

O God! that one might read the book of fate,

And see the revolution of the times

Make mountains level, and the continent,

Weary of solid firmness, melt itself

Into the sea! and, other times, to see

The beachy girdle of the ocean

Too wide for Neptune's hips; how chances mock,

And changes fill the cup of alteration

With divers liquors!

(2 Henry IV, 3.1.46), King Henry IV

Men at some time are masters of their fates:

The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars,

But in ourselves, that we are underlings.

(Julius Caesar, 1.2.146), Cassius to Brutus

It is the stars,

The stars above us, govern our conditions.

(King Lear, 4.3.37), Kent

The wheel is come full circle.

(King Lear, 5.3.203), Edmund

The sea will ebb and flow, heaven show his face,

Young blood doth not obey an old decree:

We cannot cross the cause why we were born.

(Love's Labour's Lost, 4.3.203), Biron

That I may pour my spirits in thine ear;

And chastise with the valour of my tongue

All that impedes thee from the golden round,

Which fate and metaphysical aid doth seem

To have thee crown'd withal.

(Macbeth, 1.5.27), Lady Macbeth

I fear too early, for my mind misgives

Some consequence, yet hanging in the stars

Shall bitterly begin his fearful date

With this night's revels, and expire the term

Of a dispised life, clos'd in my breast,

By some vile forfeit of untimely death.

But he that hath the steerage of my course

Direct my sail.

(Romeo and Juliet, 1.4.113), Romeo

O, I am fortune's fool!

(Romeo and Juliet, 3.1.139), Romeo

O God, I have an ill-divining soul!

(Romeo and Juliet, 3.5.55), Juliet. Romeo actually speaks this line in Q2.

O fortune, fortune! all men call thee fickle:

If thou art fickle, what dost thou with him.

That is renown'd for faith? Be fickle, fortune;

For then, I hope, thou wilt not keep him long,

But send him back.

(Romeo and Juliet, 3.5.59-63), Juliet

When in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes

I all alone beweep my outcast state.

(Sonnet 29)

By accident most strange, bountiful Fortune,

Now my dear lady, hath mine enemies

Brought to this shore; and by my prescience

I find my zenith doth depend upon

A most auspicious star, whose influence

If now I court not but omit, my fortunes

Will ever after droop.

(The Tempest, 1.2.209), Prospero to Miranda

The providence that's in a watchful state

Knows almost every grain of Plutus' gold,

Finds bottom in the uncomprehensive deeps,

Keeps place with thought and almost, like the gods,

Does thoughts unveil in their dumb cradles.

There is a mystery--with whom relation

Durst never meddle--in the soul of state;

Which hath an operation more divine

Than breath or pen can give expressure to.

(Troilus and Cressida, 3.3.207), Ulysses to Achilles

My stars shine darkly over

me: the malignancy of my fate might perhaps

distemper yours.

(Twelfth Night, 2.1.3), Sebastian to Antonio)

Famous Quotations from Romeo and Juliet Romeo and Juliet is packed with unforgettable quotations that have become a part of present-day culture. Here are the ten most famous of them all. Please visit the Romeo and Juliet main page for full explanatory notes.

1.

What's in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other word would smell as sweet.

(2.2.45-6), Juliet

2.

O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?

(2.2.35), Juliet

3.

A plague o' both your houses!

They have made worms' meat of me!

(3.1.95-6), Mercutio

4.

But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?

It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.

(2.2.2-3), Romeo

5.

A pair of star-cross'd lovers take their life.

(Prologue, 7)

6.

Good night, good night. Parting is such sweet sorrow,

That I shall say good night till it be morrow.

(2.2.197-8), Juliet

7.

See how she leans her cheek upon her hand!

O that I were a glove upon that hand,

That I might touch that cheek!

(2.2.23-5), Romeo

8.

Thus with a kiss I die.

(5.3.121), Romeo

9.

O, she doth teach the torches to burn bright.

It seems she hangs upon the cheek of night

Like a rich jewel in an Ethiop's ear.

(1.5.43-45), Romeo

10.

O happy dagger!

(5.3.175), Juliet

Honorable Mention Give me my Romeo, and, when he shall die,

Take him and cut him out in little stars,

And he will make the face of heaven so fine

That all the world will be in love with night,

And pay no worship to the garish sun.

(3.2.21-5), Juliet

A fool's paradise.

(2.4.159), Nurse

How fares my Juliet? that I ask again;

For nothing can be ill, if she be well.

(5.1.15-16), Romeo to Balthasar

This bud of love, by summer's ripening breath,

May prove a beauteous flower when next we meet.

(2.2.127-8), Juliet

1.

What's in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other word would smell as sweet.

(2.2.45-6), Juliet

2.

O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?

(2.2.35), Juliet

3.

A plague o' both your houses!

They have made worms' meat of me!

(3.1.95-6), Mercutio

4.

But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?

It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.

(2.2.2-3), Romeo

5.

A pair of star-cross'd lovers take their life.

(Prologue, 7)

6.

Good night, good night. Parting is such sweet sorrow,

That I shall say good night till it be morrow.

(2.2.197-8), Juliet

7.

See how she leans her cheek upon her hand!

O that I were a glove upon that hand,

That I might touch that cheek!

(2.2.23-5), Romeo

8.

Thus with a kiss I die.

(5.3.121), Romeo

9.

O, she doth teach the torches to burn bright.

It seems she hangs upon the cheek of night

Like a rich jewel in an Ethiop's ear.

(1.5.43-45), Romeo

10.

O happy dagger!

(5.3.175), Juliet

Honorable Mention Give me my Romeo, and, when he shall die,

Take him and cut him out in little stars,

And he will make the face of heaven so fine

That all the world will be in love with night,

And pay no worship to the garish sun.

(3.2.21-5), Juliet

A fool's paradise.

(2.4.159), Nurse

How fares my Juliet? that I ask again;

For nothing can be ill, if she be well.

(5.1.15-16), Romeo to Balthasar

This bud of love, by summer's ripening breath,

May prove a beauteous flower when next we meet.

(2.2.127-8), Juliet

Romeo and Juliet: Play History

The best information regarding the date of Romeo and Juliet comes from the title page of the first Quarto, which tells us that the play "hath been often (with great applause) plaid publiquely, by the right Honourable the L. of Hunsdon his servants."

This reference would indicate that the play was composed no later than 1596, because Hunsdon's acting troupe went by a different name after this date. Moreover, "[m]any critics have placed it as early as 1591, on account of the Nurse's reference in I.iii.22 to the earthquake of eleven years before, identifying this with an earthquake felt in England in 1580" (Neilson, Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, 36). But the earliest performance of Romeo and Juliet actually documented was in 1662, staged by William Davenant, the poet and playwright who insisted that he was Shakespeare's illegitimate son.

The play has remained extremely popular throughout the centuries, but, strangely, producers in the seventeenth century found it necessary to take great literary license with Shakespeare's original work. In some productions, Romeo and Juliet survive their ordeal to live happy, fulfilled lives. And, in 1679, Thomas Otway created a version of the play called The History and Fall of Caius Marius, set in Augustan Rome. Otway transformed the play to revolve around two opposing senators, Metellus and Marius Senior, who are fighting for political control. Metellus represents the old nobility 'fit to hold power' and he considers himself a 'worthy patron of her honor' although the followers of Marius regard him as an inglorious patrician. Marius Senior, on the other hand, is a neophyte, having held power for only six terms. He comes from a lesser stock than does Metellus, and Metellus wants to keep Marius Senior from achieving a seventh term in office. After a series of physical confrontations and a heated power struggle, Marius Senior and his men are exiled. Caught in the political struggle between their fathers are the two lovers. Note the similarities between Otway's lines and Shakespeare's famous balcony scene: O Marius, Marius! wherefore art thou Marius?

Deny thy Family, renounce thy Name:

Or if thou wilt not, be but sworn my Love,

And I'll no longer call Metellus Parent. (Caius Marius. New York: Garland, 1980 [20]). For seventy years, Otway's version trounced all productions of Shakespeare's own Romeo and Juliet. By the 1740s Shakespeare's version was again experiencing some popularity, due to revivals by several producers, including David Garrick and Theophilus Cibber. However, even they mixed other material in with Shakespeare's original text. Cibber included passages from The Two Gentlemen of Verona in his production, and Garrick opened the play with Romeo madly in love with Juliet, omitting Rosaline entirely.

In the nineteenth century, Romeo and Juliet was performed with relatively little dramatic alteration, and it became one of Shakespeare's most-produced plays and a mainstay of the English stage. With the advent of motion pictures the play reached mass audiences. More than eighteen film versions of Romeo and Juliet have been made, and by far the most popular is Franco Zeffirelli's Romeo and Juliet, filmed in 1968 and starring Olivia Hussey and Leonard Whiting. Over the last fifty years many have attempted to translate the plot of Romeo and Juliet into the modern era. The most famous of these is Leonard Bernstein's West Side Story and Luhrmann's Romeo and Juliet, starring Claire Danes and Leonardo DiCaprio.

The best information regarding the date of Romeo and Juliet comes from the title page of the first Quarto, which tells us that the play "hath been often (with great applause) plaid publiquely, by the right Honourable the L. of Hunsdon his servants."

This reference would indicate that the play was composed no later than 1596, because Hunsdon's acting troupe went by a different name after this date. Moreover, "[m]any critics have placed it as early as 1591, on account of the Nurse's reference in I.iii.22 to the earthquake of eleven years before, identifying this with an earthquake felt in England in 1580" (Neilson, Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, 36). But the earliest performance of Romeo and Juliet actually documented was in 1662, staged by William Davenant, the poet and playwright who insisted that he was Shakespeare's illegitimate son.

The play has remained extremely popular throughout the centuries, but, strangely, producers in the seventeenth century found it necessary to take great literary license with Shakespeare's original work. In some productions, Romeo and Juliet survive their ordeal to live happy, fulfilled lives. And, in 1679, Thomas Otway created a version of the play called The History and Fall of Caius Marius, set in Augustan Rome. Otway transformed the play to revolve around two opposing senators, Metellus and Marius Senior, who are fighting for political control. Metellus represents the old nobility 'fit to hold power' and he considers himself a 'worthy patron of her honor' although the followers of Marius regard him as an inglorious patrician. Marius Senior, on the other hand, is a neophyte, having held power for only six terms. He comes from a lesser stock than does Metellus, and Metellus wants to keep Marius Senior from achieving a seventh term in office. After a series of physical confrontations and a heated power struggle, Marius Senior and his men are exiled. Caught in the political struggle between their fathers are the two lovers. Note the similarities between Otway's lines and Shakespeare's famous balcony scene: O Marius, Marius! wherefore art thou Marius?

Deny thy Family, renounce thy Name:

Or if thou wilt not, be but sworn my Love,

And I'll no longer call Metellus Parent. (Caius Marius. New York: Garland, 1980 [20]). For seventy years, Otway's version trounced all productions of Shakespeare's own Romeo and Juliet. By the 1740s Shakespeare's version was again experiencing some popularity, due to revivals by several producers, including David Garrick and Theophilus Cibber. However, even they mixed other material in with Shakespeare's original text. Cibber included passages from The Two Gentlemen of Verona in his production, and Garrick opened the play with Romeo madly in love with Juliet, omitting Rosaline entirely.

In the nineteenth century, Romeo and Juliet was performed with relatively little dramatic alteration, and it became one of Shakespeare's most-produced plays and a mainstay of the English stage. With the advent of motion pictures the play reached mass audiences. More than eighteen film versions of Romeo and Juliet have been made, and by far the most popular is Franco Zeffirelli's Romeo and Juliet, filmed in 1968 and starring Olivia Hussey and Leonard Whiting. Over the last fifty years many have attempted to translate the plot of Romeo and Juliet into the modern era. The most famous of these is Leonard Bernstein's West Side Story and Luhrmann's Romeo and Juliet, starring Claire Danes and Leonardo DiCaprio.

The Theatre of Shakespeare's Day From Julius Caesar. Ed Samuel Thurber.

Let us now pay a visit to the Globe, to us the most interesting of all the theatres, for it is here that Shakespeare's company acts, and here many of his plays are first seen on the stage. We cross the Thames by London Bridge with its lines of crowded booths and shops and throngs of bustling tradesmen; or if it is fine weather we take a small boat and are rowed over the river to the southern shores. Here on the Bankside, in the part of London now called Southwark, beyond the end of the bridge, and in the open fields near the Bear Garden, stands a roundish, three-story wooden building, so high for its size that it looks more like a clumsy, squatty tower than a theatre. As we draw nearer we see that it is not exactly round after all, but is somewhat hexagonal in shape. The walls seem to slant a little inward, giving it the appearance of a huge thimble, or cocked hat, with six flattened sides instead of a circular surface. There are but few small windows and two low shabby entrances.

The whole structure is so dingy and unattractive that we stand before it in wonder. Can this be the place where "Hamlet," "The Merchant of Venice," and "Julius Caesar" are put on the stage? Our amazement on stepping inside is even greater. The first thing that astonishes us is the blue sky over our heads. The building has no roof except a narrow strip around the edge and a covering at the rear over the back part of the stage.

The front of the stage and the whole center of the theatre is open to the air. Now we see how the interior is lighted, though with the sunshine must often come rain and sleet and London fog. Looking up and out at the clouds floating by, we notice that a flag is flying from a short pole on the roof over the stage. This is most important, for it is announcing to the city across the river that this afternoon there is to be a play. It is bill-board, newspaper notice, and advertisement in one: and we may imagine the eagerness with which it is looked for among the theatre-loving populace of these later Elizabethan years. When the performance begins the flag will be lowered to proclaim to all that "the play is on."

Where, now, shall we sit? Before us on the ground level is a large open space, which corresponds to the orchestra circle on the floor of a modern play-house. But here there is only the flat bare earth, trodden down hard, with rushes and in the straw scattered over it. There is not a sign of a seat! This is the "yard," or, as it is sometimes called, "the pit," where, by paying a penny or two, London apprentices, sailors, laborers, and the mixed crowd from the streets may stand jostling together. Some of the more enterprising ones may possibly sit on boxes and stools which they bring into the building with them. Among these "groundlings" there will surely be bustling confusion, noisy wrangling, and plenty of danger from pickpockets; so we look about us to find a more comfortable place from which to watch the performance.

On three sides of us, and extending well around the stage, are three tiers of narrow balconies. In some places these are divided into compartments, or boxes. The prices here are higher, varying from a few pennies to half a crown, according to the location. By putting our money into a box held out to us, -- there are no tickets, -- we are allowed to climb the crooked wooden stairs to one of these compartments. Here we find rough benches and chairs, and above all a little seclusion from the throng of men and boys below.

Along the edge of the stage we observe that there are stools, but these places, elevated and facing the audience, seem rather conspicuous, and besides the prices are high. They will be taken by the young gallants and men of fashion of London, in brave and brilliant clothes, with light swords at their belts, wide ruffled collars about their necks, and gay plunies in their hats. It will be amusing to see them show off their fine apparel, and display their wit at the expense of the groundlings in the pit, and even of the actors themselves. We are safer, however, and much more comfortable here in the balcony among the more sober, quiet gentlemen of London, who with mechanics, tradesmen, nobles, and shop-keepers have come to see the play.

The moment we entered the theatre we were impressed by the size of the stage. Looking down upon it from the balcony, it seems even larger and very near us. If it is like the stage of the Fortune it is square.... Here in the Globe it is probably narrower at the front than at the back, tapering from the rear wall almost to a point. Whatever its shape, it is only a roughly-built, high platform, open on three sides, and extending halfway into the "yard." Though a low railing runs about its edge, there are no footlights, -- all performances are in the afternoon by the light of day which streams down through the open top, -- and strangest of all there is no curtain. At each side of the rear we can see a door that leads to the "tiring-rooms" where the actors dress, and from which they make their entrances. These are the "green-rooms" and wings of our theatre today.

Between the doors is a curtain that now before the play begins is drawn together. Later when it is pulled aside, -- not upward as curtains usually are now, -- we shall see a shallow recess or alcove which serves as a secondary, or inner stage. Over this extends a narrow balcony covered by a roof which is supported at the front corners by two columns that stand well out from the wall. Still higher up, over the inner stage, is a sort of tower, sometimes called the "hut," and from a pole on this the flag is flying which summons the London populace from across the Thames. Rushes are strewn over the floor; there are no drops or wings or walls of painted scenery. In its simplicity and bareness it reminds us of the rude stage of the strolling players. Indeed, the whole interior of the building seems to be but an adaptation of the tavern-yard and village-green.

How, we wonder, can a play like "Julius Caesar" or "The Merchant of Venice" be staged on such a crude affair as this! What are the various parts of it for? Practically all acting is done, we shall see see, on the front of the platform well out among the crowd in the pit, with the audience on three sides of the performers. All out-of-door scenes will be acted here, from a conversation in the streets of Venice or a dialogue in a garden, to a battle, a procession, or a banquet in the Forest of Arden. Here, too, with but the slightest alteration, or even with no change at all, interior scenes will be presented. With the "groundlings" crowded close up to its edges, and with young gallants sitting on its sides, this outer stage comes close to the people. On it will be all the main action of the drama: the various arrangements at the rear are for supplementary purposes and certain important effects.

The inner stage, or alcove beyond the curtain, is used in many ways. It may serve for any room somewhat removed from the scene of action, such as a passage-way or a study. It often is made to represent a cave, a shop, or a prison. Here Othello, in a frenzy of jealous passion, strangles Desdemona as she lies in bed; here probably the ghost of Caesar appears to Brutus in his tent on the plains of Philippi; here stand the three fateful caskets in the mansion at Belmont, as we see by Portia's words, "Go, draw aside the curtains and discover

The several caskets to this noble Prince." Tableaux and scenes within scenes, such as the short play in "Hamlet" by which the prince "catches the conscience of the king," are acted in this recess. But the most important use is to give the effect of a change of scene. By drawing apart and closing the curtain, with a few simple changes of properties in this inner compartment, a different background is possible. By such a slight variation of setting at the rear, the platform in the pit is transformed, by the quick imagination of the spectators, from a field or a street to a castle hall or a wood. Thus, the whole stage becomes the Forest of Arden by the use of a little greenery in the distance. Similarly, a few trees and shrubs at the rear of the inner stage, when the curtain is thrown aside, will change the setting from the court-room in the fourth act of "The Merchant of Venice," to the scene in the garden at Belmont which immediately follows.

The balcony over the inner stage serves an important purpose, too. With the windows, which are often just over the doors leading to the tiring-rooms, it gives the effect of an upper story of a house, of walls in a castle, a tower, or any elevated over the position. This is the place, of course, where Juliet comes to greet Romeo who is in the garden below. In "Julius Caesar" when Cassius says, "Go Pindarus, get higher on that hill;....

And tell me what thou notest about the field," the soldier undoubtedly climbs to the balcony, for a moment later, looking abroad over the field of battle, he reports to Cassius what he sees from his elevation. Here Jessica appears when Lorenzo calls under Shylock's windows, "Ho! who's within?" and on this balcony she is standing when she throws down to her lover a box of her father's jewels. "Here, catch this casket; it is worth the pains," she says, and retires into the house, appearing below a moment later to run away with Lorenzo and his masquerading companions.

Besides these simple devices, if we look closely enough we shall see a trap-door, or perhaps two, in the platform. These are for the entrance of apparitions and demons. They correspond, in a way, to the balcony by giving the effect of a place lower than the stage level. Thus in the first scene of "The Tempest," which takes place in a storm at sea, the notion of a ship may be suggested to the audience by sailors entering from the trap-door, as they might come up a hatchway to a deck. If it is a play with gods and goddesses and spirits, we may be startled to see them appear and disappear through the air. Evidently there is machinery of some sort in the hut over the balcony which can be used for lowering and raising deities and creatures that live above the earth. On each side of the stage is a flight of steps leading to the balcony. These are often covered... Here sit councils, senates, and princes with their courts. Macbeth uses them to give the impression of ascending to an upper chamber when he goes to kill the king, and down them he rushes to his wife after he has committed the fearful murder.

What astonishes us most, however, is the absence of scenery. To be sure, some slight attempt has been made to create scenic illusion. There are, perhaps, a few trees and boulders, a table, a chair or two, and pasteboard dishes of food. But there is little more. In the only drawing of the interior of an Elizabethan theatre that has been preserved, -- a sketch of the Swan made in 1596, -- the stage has absolutely no furniture except one plain bench on which one of the actors is sitting. Here before us in the Globe the walls may be covered with loose tapestries, black if the play is to be a tragedy, blue if a comedy; but it is quite possible that they are entirely bare. A placard on one of the pillars announces that the stage is now a street in Venice, now a courtroom, now the hall of a stately mansion. It may be that the Prologue, or even the actors themselves, will tell us at the opening of an act just where the scene is laid and what we are to imagine the platform to represent.

In "Henry V," for instance, the Prologue at the beginning not only explains the setting of the play, but asks forgiveness of the audience for attempting to put on the stage armies and battles and the "vasty fields of France." "But pardon, gentles all,

The flat unraised spirit that hath dared

On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth

So great an object. Can this cockpit hold

The vasty fields of France? or may we cram

Within this wooden O the very casques

That did affright the air at Agincourt?

O, pardon! since a crooked figure may

Attest in little place a million;

And let us, ciphers to this great accompt,

On your imaginary forces work.

Suppose within the girdle of these walls

Are now confined two mighty monarchies,

Whose high-upreared and abutting fronts

The perilous, narrow ocean parts asunder.

Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts;

Into a thousand parts divide one man,

And make imaginary puissance.

Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them

Printing their proud hoofs i' the receiving earth,

For 'tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings,

Carry them here and there, jumping o'er times.

Turning the accomplishment of many years

Into an hour-glass." In "As You Like It" it is an actor who tells us at the opening of the second act that we are now to imagine the Forest of Arden before us. In the first sentence which the banished Duke speaks, he says, "Are not these woods more free from peril than the envious court?" and a moment later, when Touchstone and the runaway maidens first enter the woods, Rosalind exclaims, "Well, this is the Forest of Arden!" A hint, a reference, a few simple contrivances, a placard or two, -- these are enough. "Imaginary forces" are here in the audience keenly alive, and they will do the rest. By means of them, without the illusion of scenery, the bare wooden stage will become a ship, a garden, a palace, a London tavern. Whole armies will enter and retire by a single door. Battles will rage, royal processions pass in and out, graves will be dug, lovers will woo, -- and all with hardly an important alteration of the setting.

Lack of scenery does not limit the type of scenes that can be presented. On the contrary, it gives almost unlimited opportunities to the dramatist, for the spectators, in the force and freshness of their imagination, are children who willingly "play" that the stage is anything the author suggests. Their youthful enthusiasm, their simple tastes, above all their lack of knowledge of anything different, give them the enviable power of imagining the grandest, most beautiful, and most varied scenes on the same bare, unadorned boards. Apparently they are well satisfied with their stage; for it is not until nearly fifty years after Shakespeare's death that movable scenery is used in an English theatre.

It is now three o'clock and time for the performance to begin. Among the motley crowd of men and boys in the yard there is no longer room for another box or stool. They are evidently growing impatient and jostle together in noisy confusion. Suddenly three long blasts on a trumpet sound. The mutterings in the pit subside, and all eyes turn toward the stage. First an actor, clothed in a black mantle and wearing a laurel wreath on his head, comes from behind the curtain and recites the prologue. From it we learn something of the story of the play to follow, and possibly a little about the scene of action. This is all very welcome, for we have no programs and the plot of the drama is unfamiliar. In a minute or two the Prologue retires and the actors of the first scene enter. We are soon impressed by the rapidity with which the play moves on. There is little stage "business"; though there may be some music between the acts, still there are no long waits; one scene follows another as quickly as the actors can make their exits and entrances. The whole play, therefore, does not last much over two hours. At the close there is an epilogue, spoken by one of the actors, after which the players kneel and join in a prayer for the queen. Then comes a final bit of amusement for the groundlings: the clown, or some other comic character of the company, sings a popular song, dances a brisk and boisterous jig, and the performance of the day is done.

During our novel experience this afternoon at the Globe, nothing has probably surprised us more than the elaborate and gorgeous costumes of the actors. At a time when so little attention is paid to of the scenery we naturally expect to find the dress of the players equally simple and plain. But we are mistaken. The costumes, to be sure, make little or no pretension to fit the period or place of action. Caesar appears in clothes such as are worn by a duke or an earl in 1601. "They are the ordinary dresses of various classes of the day, but they are often of rich material, and in the height of current fashion. False hair and beards, crowns and sceptres, mitres and croziers, armour, helmets, shields, vizors, and weapons of war, hoods, bands, and cassocks, are relied on to indicate among the characters differences of rank or profession.

The foreign observer, Thomas Platter of Basle, was impressed by the splendor of the actors' costumes. 'The players wear the most costly and beautiful dresses, for it is the custom in England, that when noblemen or knights die, they leave their finest clothes to their servants, who, since it would not be fitting for them to wear such splendid garments, sell them soon afterwards to the players for a small sum'" (Sidney Lee, Shakespeare and the Modern Stage, p. 41). But no money is spared to secure the fitting garment for an important part. Indeed, it is quite probable that more is paid for a king's velvet robe or a prince's silken doublet than is given to the author for the play itself. Whether the elaborate costumes are appropriate or not, their general effect is pleasing, for they give variety and brilliant color to the bare and unattractive stage.

If we are happily surprised by the costuming of the play, what shall we say of the actors who take the female parts! They are very evidently not women, or even girls, but boys whose voices have not changed, dressed, tricked out, and trained to appear as feminine as possible. It is considered unseemly for a woman to appear on a public stage, -- indeed, the professional actress does not exist and will not be seen in an English theatre for nearly a century.

Meanwhile plays are written with few female parts (remember "The Merchant of Venice," "Julius Caesar," and "Macbeth") and young boys are trained to take these roles. The theatregoers seem to enjoy the performance just as much as we do today with mature and accomplished actresses on the stage. Shakespeare and his fellow dramatists treated the situation with good grace or indifference. Thus in the epilogue of "As You Like It" Rosalind says to the audience, "If I were a woman I would kiss as many of you as had beards that pleased me." The jest, of course, consists in the fact that she is not a woman at all, but a stripling.

In a more tragic vein Cleopatra, before she dies, complains that "the quick comedians . . . will stage us, . . . and I shall see some squeaking Cleopatra boy my greatness." It may be that the boys who take the women's parts this afternoon wear masks to make them seem less masculine, though how that can improve the situation it is difficult to understand. There is an amusing reference to this practice in "A Midsummer Night's Dream." When Flute, the bellows-mender, is assigned a part in the drama which the mechanics of Athens are rehearsing, he exclaims, "Nay, faith, let me not play a woman; I have a beard coming"; to which protest Quince replies, "That's all one: you shall play it in a mask, and you may speak as small as you will."

Though rapid action, brilliant costumes, and, above all, the force and beauty of the lines, may lead us to forget that the heroine is only a boy, it is more difficult to keep our attention from being distracted by the audience around us. It surprises us at the that there are so few women present. We notice, too, that many of those who have come wear a mask of silk or velvet over their faces. Evidently it is hardly the proper thing for a respectable woman to be seen in a public theatre. The people in the balconies are fairly orderly, but below in the pit the crowd is restless, noisy, and at times even boisterous. Bricklayers, dock-laborers, apprentices, serving-men, and idlers stand in jostling confusion. There are no police and no laws that are enforced. Pickpockets ply an active trade.

One, we see, has been caught and is bound to the railing at the edge of the stage where he is an object of coarse jests and ridicule. Refreshment-sellers push about in the throng with apples and sausages, nuts and ale. There is much eating and drinking and plenty of smoking. On the stage the gallants are a constant source of bother to the players. They interrupt the Prologue, criticise the dress of the hero, banter the heroine, and joke with the clown. Even here in the gallery we can hear their comments -- far from flattering -- upon a scene that does not please them; when a little later they applaud, their praises are just as vigorous. Once it seems as though the play is going to be brought to a standstill by a wrangling quarrel between one of these rakish gentlemen and a group of groundlings near the stage. Their attention, however, is taken by the entrance of the leading actor declaiming a stirring passage, and their differences are soon forgotten.

It is, on the whole, a good-natured rough crowd of the common people, the lower and middle classes from the great city across the river, -- more like the crowd one sees today at a circus or a professional ball-game than at a theatre of the highest type. They loudly cheer the clown's final song and dance, and then with laughter, shouting, and jesting they pour out of the yard and in a moment the building is empty. The play is over until tomorrow afternoon.

What a contrast it all has been to a play in a theatre of the twentieth century! When we think of the uncomfortable benches, the flat bare earth of the pit, the lack of scenery, footlights, and drop curtains ; when we hear the shrill voices of boys piping the women's parts, and see mist and rain falling on spectator's heads, we are inclined to pity the playgoer of Elizabethan times. Yet he needs no pity. To him the theatre of his day was sufficient.

The drama enacted there was a source of intense and genuine pleasure. His keen enthusiasm; his fresh, youthful eagerness; above all, his highly imaginative power, -- far greater than ours today, -- gave him an ability to understand and enjoy the poetry and dramatic force of Shakespeare's works, which we, with all the improvements of our palatial theatres, cannot equal. Crude, simple, coarse as they now seem to us, we can look back only with admiration upon the Swan and the Curtain and the Globe; for in them "The Merchant of Venice," "As You Like It," "Julius Caesar," "Hamlet," and "Macbeth" were received with acclamations of joy and wonder.

In them the genius of Shakespeare was recognized and given a place in the drama of England which now, after three centuries have passed, it holds in the theatres and in the literature of all the world.

Let us now pay a visit to the Globe, to us the most interesting of all the theatres, for it is here that Shakespeare's company acts, and here many of his plays are first seen on the stage. We cross the Thames by London Bridge with its lines of crowded booths and shops and throngs of bustling tradesmen; or if it is fine weather we take a small boat and are rowed over the river to the southern shores. Here on the Bankside, in the part of London now called Southwark, beyond the end of the bridge, and in the open fields near the Bear Garden, stands a roundish, three-story wooden building, so high for its size that it looks more like a clumsy, squatty tower than a theatre. As we draw nearer we see that it is not exactly round after all, but is somewhat hexagonal in shape. The walls seem to slant a little inward, giving it the appearance of a huge thimble, or cocked hat, with six flattened sides instead of a circular surface. There are but few small windows and two low shabby entrances.

The whole structure is so dingy and unattractive that we stand before it in wonder. Can this be the place where "Hamlet," "The Merchant of Venice," and "Julius Caesar" are put on the stage? Our amazement on stepping inside is even greater. The first thing that astonishes us is the blue sky over our heads. The building has no roof except a narrow strip around the edge and a covering at the rear over the back part of the stage.

The front of the stage and the whole center of the theatre is open to the air. Now we see how the interior is lighted, though with the sunshine must often come rain and sleet and London fog. Looking up and out at the clouds floating by, we notice that a flag is flying from a short pole on the roof over the stage. This is most important, for it is announcing to the city across the river that this afternoon there is to be a play. It is bill-board, newspaper notice, and advertisement in one: and we may imagine the eagerness with which it is looked for among the theatre-loving populace of these later Elizabethan years. When the performance begins the flag will be lowered to proclaim to all that "the play is on."

Where, now, shall we sit? Before us on the ground level is a large open space, which corresponds to the orchestra circle on the floor of a modern play-house. But here there is only the flat bare earth, trodden down hard, with rushes and in the straw scattered over it. There is not a sign of a seat! This is the "yard," or, as it is sometimes called, "the pit," where, by paying a penny or two, London apprentices, sailors, laborers, and the mixed crowd from the streets may stand jostling together. Some of the more enterprising ones may possibly sit on boxes and stools which they bring into the building with them. Among these "groundlings" there will surely be bustling confusion, noisy wrangling, and plenty of danger from pickpockets; so we look about us to find a more comfortable place from which to watch the performance.

On three sides of us, and extending well around the stage, are three tiers of narrow balconies. In some places these are divided into compartments, or boxes. The prices here are higher, varying from a few pennies to half a crown, according to the location. By putting our money into a box held out to us, -- there are no tickets, -- we are allowed to climb the crooked wooden stairs to one of these compartments. Here we find rough benches and chairs, and above all a little seclusion from the throng of men and boys below.

Along the edge of the stage we observe that there are stools, but these places, elevated and facing the audience, seem rather conspicuous, and besides the prices are high. They will be taken by the young gallants and men of fashion of London, in brave and brilliant clothes, with light swords at their belts, wide ruffled collars about their necks, and gay plunies in their hats. It will be amusing to see them show off their fine apparel, and display their wit at the expense of the groundlings in the pit, and even of the actors themselves. We are safer, however, and much more comfortable here in the balcony among the more sober, quiet gentlemen of London, who with mechanics, tradesmen, nobles, and shop-keepers have come to see the play.

The moment we entered the theatre we were impressed by the size of the stage. Looking down upon it from the balcony, it seems even larger and very near us. If it is like the stage of the Fortune it is square.... Here in the Globe it is probably narrower at the front than at the back, tapering from the rear wall almost to a point. Whatever its shape, it is only a roughly-built, high platform, open on three sides, and extending halfway into the "yard." Though a low railing runs about its edge, there are no footlights, -- all performances are in the afternoon by the light of day which streams down through the open top, -- and strangest of all there is no curtain. At each side of the rear we can see a door that leads to the "tiring-rooms" where the actors dress, and from which they make their entrances. These are the "green-rooms" and wings of our theatre today.

Between the doors is a curtain that now before the play begins is drawn together. Later when it is pulled aside, -- not upward as curtains usually are now, -- we shall see a shallow recess or alcove which serves as a secondary, or inner stage. Over this extends a narrow balcony covered by a roof which is supported at the front corners by two columns that stand well out from the wall. Still higher up, over the inner stage, is a sort of tower, sometimes called the "hut," and from a pole on this the flag is flying which summons the London populace from across the Thames. Rushes are strewn over the floor; there are no drops or wings or walls of painted scenery. In its simplicity and bareness it reminds us of the rude stage of the strolling players. Indeed, the whole interior of the building seems to be but an adaptation of the tavern-yard and village-green.

How, we wonder, can a play like "Julius Caesar" or "The Merchant of Venice" be staged on such a crude affair as this! What are the various parts of it for? Practically all acting is done, we shall see see, on the front of the platform well out among the crowd in the pit, with the audience on three sides of the performers. All out-of-door scenes will be acted here, from a conversation in the streets of Venice or a dialogue in a garden, to a battle, a procession, or a banquet in the Forest of Arden. Here, too, with but the slightest alteration, or even with no change at all, interior scenes will be presented. With the "groundlings" crowded close up to its edges, and with young gallants sitting on its sides, this outer stage comes close to the people. On it will be all the main action of the drama: the various arrangements at the rear are for supplementary purposes and certain important effects.

The inner stage, or alcove beyond the curtain, is used in many ways. It may serve for any room somewhat removed from the scene of action, such as a passage-way or a study. It often is made to represent a cave, a shop, or a prison. Here Othello, in a frenzy of jealous passion, strangles Desdemona as she lies in bed; here probably the ghost of Caesar appears to Brutus in his tent on the plains of Philippi; here stand the three fateful caskets in the mansion at Belmont, as we see by Portia's words, "Go, draw aside the curtains and discover

The several caskets to this noble Prince." Tableaux and scenes within scenes, such as the short play in "Hamlet" by which the prince "catches the conscience of the king," are acted in this recess. But the most important use is to give the effect of a change of scene. By drawing apart and closing the curtain, with a few simple changes of properties in this inner compartment, a different background is possible. By such a slight variation of setting at the rear, the platform in the pit is transformed, by the quick imagination of the spectators, from a field or a street to a castle hall or a wood. Thus, the whole stage becomes the Forest of Arden by the use of a little greenery in the distance. Similarly, a few trees and shrubs at the rear of the inner stage, when the curtain is thrown aside, will change the setting from the court-room in the fourth act of "The Merchant of Venice," to the scene in the garden at Belmont which immediately follows.

The balcony over the inner stage serves an important purpose, too. With the windows, which are often just over the doors leading to the tiring-rooms, it gives the effect of an upper story of a house, of walls in a castle, a tower, or any elevated over the position. This is the place, of course, where Juliet comes to greet Romeo who is in the garden below. In "Julius Caesar" when Cassius says, "Go Pindarus, get higher on that hill;....

And tell me what thou notest about the field," the soldier undoubtedly climbs to the balcony, for a moment later, looking abroad over the field of battle, he reports to Cassius what he sees from his elevation. Here Jessica appears when Lorenzo calls under Shylock's windows, "Ho! who's within?" and on this balcony she is standing when she throws down to her lover a box of her father's jewels. "Here, catch this casket; it is worth the pains," she says, and retires into the house, appearing below a moment later to run away with Lorenzo and his masquerading companions.

Besides these simple devices, if we look closely enough we shall see a trap-door, or perhaps two, in the platform. These are for the entrance of apparitions and demons. They correspond, in a way, to the balcony by giving the effect of a place lower than the stage level. Thus in the first scene of "The Tempest," which takes place in a storm at sea, the notion of a ship may be suggested to the audience by sailors entering from the trap-door, as they might come up a hatchway to a deck. If it is a play with gods and goddesses and spirits, we may be startled to see them appear and disappear through the air. Evidently there is machinery of some sort in the hut over the balcony which can be used for lowering and raising deities and creatures that live above the earth. On each side of the stage is a flight of steps leading to the balcony. These are often covered... Here sit councils, senates, and princes with their courts. Macbeth uses them to give the impression of ascending to an upper chamber when he goes to kill the king, and down them he rushes to his wife after he has committed the fearful murder.