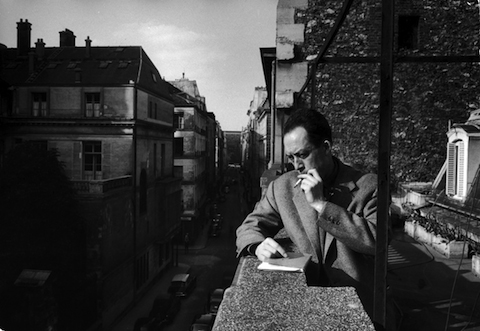

Albert Camus

What would you do if you won a Nobel Prize? Who would you thank? We’ve all wondered about it, perhaps not about the Nobel specifically, but about some potentially legacy-confirming prize or other — maybe an Oscar, maybe a MacArthur Fellowship. When Albert Camus, the short-lived French novelist-philosopher who wrote such enduring works as The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus, won the Nobel for Literature in 1957 “for his important literary production, which with clear-sighted earnestness illuminates the problems of the human conscience in our times,” he thanked an elementary-school teacher. “One could argue that, in the history of the field, few teacher-pupil relationships have had more dramatic impact than that of Louis Germain on his young pupil Albert Camus,” says a Chicago Tribune article published during an upswing in American interest in Camus’ work. That happened soon after the publication of his unfinished autobiographical novel The First Man, a “classic story of a poor boy who made good” whose appendix includes the author’s real-life correspondence with his former teacher.

One of these letters Camus wrote to Germain not long after winning the Nobel. (You can hear his actual acceptance speech here.) He no doubt saw the older man’s formative influence as essential to the work that brought that prestigious prize his way, since, as Letters of Note puts it, “he was just 11-months-old when his father was killed in action during The Battle of the Marne; his mother, partially deaf and illiterate, then raised her boys in extreme poverty with the help of his heavy-handed grandmother. It was in school that Camus shone, due in no small part to the encouragement offered by his beloved teacher.” Though never thrilled about public honors of this type, Camus nonetheless knew a chance to express long-felt gratitude when he saw it, and to Germain he wrote these sentences as brief and as powerful as many in his books:

19 November 1957

Dear Monsieur Germain,

I let the commotion around me these days subside a bit before speaking to you from the bottom of my heart. I have just been given far too great an honour, one I neither sought nor solicited.

But when I heard the news, my first thought, after my mother, was of you. Without you, without the affectionate hand you extended to the small poor child that I was, without your teaching and example, none of all this would have happened.

I don’t make too much of this sort of honour. But at least it gives me the opportunity to tell you what you have been and still are for me, and to assure you that your efforts, your work, and the generous heart you put into it still live in one of your little schoolboys who, despite the years, has never stopped being your grateful pupil. I embrace you with all my heart.

Albert Camus

One of these letters Camus wrote to Germain not long after winning the Nobel. (You can hear his actual acceptance speech here.) He no doubt saw the older man’s formative influence as essential to the work that brought that prestigious prize his way, since, as Letters of Note puts it, “he was just 11-months-old when his father was killed in action during The Battle of the Marne; his mother, partially deaf and illiterate, then raised her boys in extreme poverty with the help of his heavy-handed grandmother. It was in school that Camus shone, due in no small part to the encouragement offered by his beloved teacher.” Though never thrilled about public honors of this type, Camus nonetheless knew a chance to express long-felt gratitude when he saw it, and to Germain he wrote these sentences as brief and as powerful as many in his books:

19 November 1957

Dear Monsieur Germain,

I let the commotion around me these days subside a bit before speaking to you from the bottom of my heart. I have just been given far too great an honour, one I neither sought nor solicited.

But when I heard the news, my first thought, after my mother, was of you. Without you, without the affectionate hand you extended to the small poor child that I was, without your teaching and example, none of all this would have happened.

I don’t make too much of this sort of honour. But at least it gives me the opportunity to tell you what you have been and still are for me, and to assure you that your efforts, your work, and the generous heart you put into it still live in one of your little schoolboys who, despite the years, has never stopped being your grateful pupil. I embrace you with all my heart.

Albert Camus