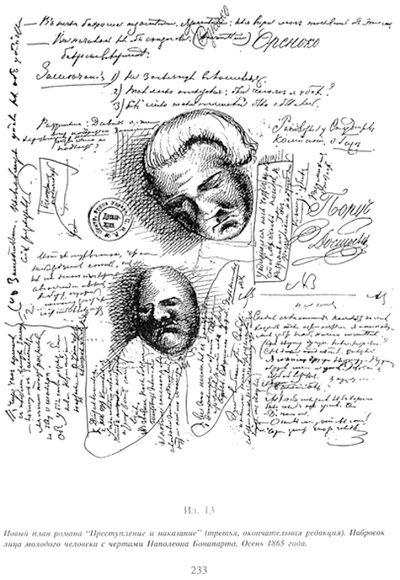

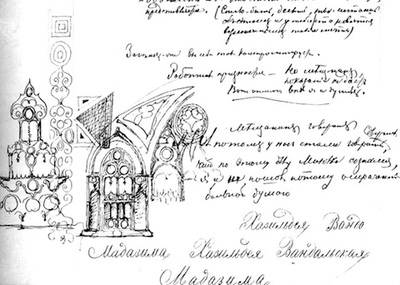

Few would argue against the claim that Fyodor Dostoevsky, author of such bywords for literary weightiness as Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, and The Brothers Karamazov, mastered the novel, even by the formidable standards of 19th-century Russia. But if you look into his papers, you’ll find that he also had an intriguing way with pen and ink outside the realm of letters — or, if you like, deep inside the realm of letters, since to see drawings by Dostoevsky, you actually have to look within the manuscripts of his novels. Above, we have a page from Crime and Punishment into which a pair of solemn faces (not that their mood will surprise enthusiasts of Russian literature) found their way. Just below, you’ll find examples from the same manuscript of his pen turning toward the ornamental and architectural while he “created his fiction step by step as he lived, read, remembered, reprocessed and wrote,” as the exhibition of “Dostoyevsky’s Doodles” at Columbia University’s Harriman Institute of Russian, Eurasian, and East European Studies put it.

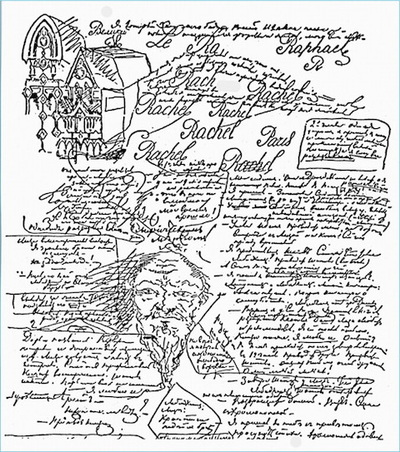

According to the exhibition description, Dostoevsky’s notes to himself “represent that key moment when the accumulated proto-novel crystallized into a text. Like many of us, Dostoevsky doodled hardest when the words came slowest.” Some of Dostoevsky’s character descriptions, argues scholar Konstantin Barsht, “are actually the descriptions of doodled portraits he kept reworking until they were right.” He didn’t just do so during the writing of Crime and Punishment, either; below we have a page of The Devils that combines the human, the architectural, and the calligraphic, apparently the three main avenues through which Dostoevsky pursued the doodler’s art. Even if you would personally argue against his claim to greatness (and thus side with his countryman, colleague in literature, and fellow part-time artist Vladimir Nabokov, who found him a “mediocre” writer given to “wastelands of literary platitudes”), surely you can enjoy the charge of pure creation you feel from witnessing his textual mind interact with his visual one. Works by Dostoevsky can be found in our Free Audio Books and Free eBooks collections.

According to the exhibition description, Dostoevsky’s notes to himself “represent that key moment when the accumulated proto-novel crystallized into a text. Like many of us, Dostoevsky doodled hardest when the words came slowest.” Some of Dostoevsky’s character descriptions, argues scholar Konstantin Barsht, “are actually the descriptions of doodled portraits he kept reworking until they were right.” He didn’t just do so during the writing of Crime and Punishment, either; below we have a page of The Devils that combines the human, the architectural, and the calligraphic, apparently the three main avenues through which Dostoevsky pursued the doodler’s art. Even if you would personally argue against his claim to greatness (and thus side with his countryman, colleague in literature, and fellow part-time artist Vladimir Nabokov, who found him a “mediocre” writer given to “wastelands of literary platitudes”), surely you can enjoy the charge of pure creation you feel from witnessing his textual mind interact with his visual one. Works by Dostoevsky can be found in our Free Audio Books and Free eBooks collections.