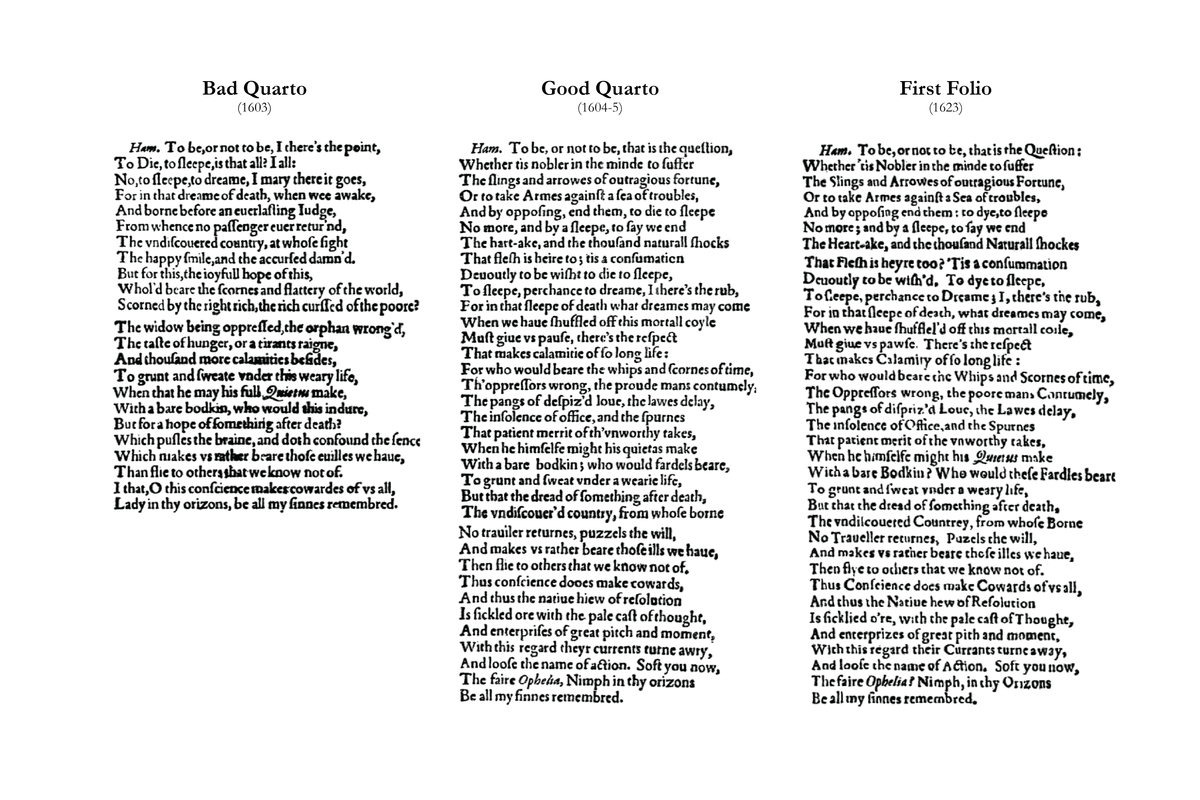

"Bad quarto, good quarto, first folio" by Georgelazenby - Own work. Licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

I enjoy replaying this vintage gem every now and then — Malcolm X debating at Oxford University in 1964. In this classic video, you get a good feel for Malcolm X’s presence and message, not to mention the social issues that were alive during the day. You’ll hear X’s trademark claim that liberty can be attained by “whatever means necessary,” including force, if the government won’t guarantee it, and that “intelligently directed extremism” will achieve liberty far more effectively than pacifist strategies. (He’s clearly alluding to Martin Luther King.) You can listen to the speech in its entirety here (Real Audio), something that is well worth doing. But I’d also encourage you to watch the dramatic closing minutes and pay some attention to the nice rhetorical slide, where X takes lines from Shakespeare’s Hamlet and uses them to justify his “by whatever means necessary” position. You’d probably never expect to see Hamlet getting invoked that way, let alone Malcolm X speaking at Oxford. A wonderful set of contrasts.

“I read once, passingly, about a man named Shakespeare. I only read about him passingly, but I remember one thing he wrote that kind of moved me. He put it in the mouth of Hamlet, I think, it was, who said, ‘To be or not to be.’ He was in doubt about something—whether it was nobler in the mind of man to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune—moderation—or to take up arms against a sea of troubles and by opposing end them. And I go for that. If you take up arms, you’ll end it, but if you sit around and wait for the one who’s in power to make up his mind that he should end it, you’ll be waiting a long time. And in my opinion, the young generation of whites, blacks, browns, whatever else there is, you’re living at a time of extremism, a time of revolution, a time when there’s got to be a change. People in power have misused it, and now there has to be a change and a better world has to be built, and the only way it’s going to be built—is with extreme methods. And I, for one, will join in with anyone—I don’t care what color you are—as long as you want to change this miserable condition that exists on this earth.”

“I read once, passingly, about a man named Shakespeare. I only read about him passingly, but I remember one thing he wrote that kind of moved me. He put it in the mouth of Hamlet, I think, it was, who said, ‘To be or not to be.’ He was in doubt about something—whether it was nobler in the mind of man to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune—moderation—or to take up arms against a sea of troubles and by opposing end them. And I go for that. If you take up arms, you’ll end it, but if you sit around and wait for the one who’s in power to make up his mind that he should end it, you’ll be waiting a long time. And in my opinion, the young generation of whites, blacks, browns, whatever else there is, you’re living at a time of extremism, a time of revolution, a time when there’s got to be a change. People in power have misused it, and now there has to be a change and a better world has to be built, and the only way it’s going to be built—is with extreme methods. And I, for one, will join in with anyone—I don’t care what color you are—as long as you want to change this miserable condition that exists on this earth.”

To Be Or Not To Be: Hamlet Soliloquy Other Hamlet Soliloquies:

- O that this too too solid flesh would melt

- O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I

- How all occasions do inform against me

- Oh my offence is rank, it smells to heaven

- Now might I do it pat

To Be, Or Not To Be (Spoken by Hamlet, Act 3 Scene 1) To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die: to sleep;

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to, 'tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep;

To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub;

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause: there's the respect

That makes calamity of so long life;

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law's delay,

The insolence of office and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscover'd country from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all;

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.--Soft you now!

The fair Ophelia! Nymph, in thy orisons

Be all my sins remember'd.

"To Be Or Not To Be" Soliloquy Translation:

The question for him was whether to continue to exist or not - whether it was more noble to suffer the slings and arrows of an unbearable situation, or to declare war on the sea of troubles that afflict one, and by opposing them, end them. To die. He pondered the prospect. To sleep - as simple as that. And with that sleep we end the heartaches and the thousand natural miseries that human beings have to endure. It's an end that we would all ardently hope for. To die. To sleep. To sleep. Perhaps to dream. Yes, that was the problem, because in that sleep of death the dreams we might have when we have shed this mortal body must make us pause. That's the consideration that creates the calamity of such a long life. Because, who would tolerate the whips and scorns of time; the tyrant's offences against us; the contempt of proud men; the pain of rejected love; the insolence of officious authority; and the advantage that the worst people take of the best, when one could just release oneself with a naked blade? Who would carry this load, sweating and grunting under the burden of a weary life if it weren't for the dread of the after life - that unexplored country from whose border no traveler returns? That's the thing that confounds us and makes us put up with those evils that we know rather than hurry to others that we don't know about. So thinking about it makes cowards of us all, and it follows that the first impulse to end our life is obscured by reflecting on it. And great and important plans are diluted to the point where we don't do anything.

Probably the best-known lines in English literature, Hamlet's greatest soliloquy is the source of more than a dozen everyday (or every month) expressions—the stuff that newspaper editorials and florid speeches are made on. Rather than address every one of these gems, I've selected a few of the richer ones for comment. But rest assured that you can quote any line and people will recognize your erudition.

Hamlet, in contemplating the nature of action, characteristically waxes existential, and it is this quality—the sense that here we have Shakespeare's own ideas on the meaning of life and death—that has made the speech so quotable. Whether or not Shakespeare endorsed Hamlet's sentiments, he rose to the occasion with a very great speech on the very great topic of human "being."

The subtle twists and turns of the prince's language I shall leave to the critics. My focus will be on the isolated images Hamlet invokes, the forgotten pictures behind the words, the parts we ignore when we quote the sum.

TO BE, OR NOT TO BE, THAT IS THE QUESTION If you follow Hamlet's speech carefully, you'll notice that his notions of "being" and "not being" are rather complex. He doesn't simply ask whether life or death is preferable; it's hard to clearly distinguish the two—"being" comes to look a lot like "not being," and vice versa. To be, in Hamlet's eyes, is a passive state, to "suffer" outrageous fortune's blows, while not being is the action of opposing those blows. Living is, in effect, a kind of slow death, a submission to fortune's power. On the other hand, death is initiated by a life of action, rushing armed against a sea of troubles—a pretty hopeless project, if you think about it.

TO SLEEP, PERCHANCE TO DREAM Hamlet tries to take comfort in the idea that death is really "no more" than a kind of sleep, with the advantage of one's never having to get up in the morning. This is a "consummation"—a completion or perfection—"devoutly to be wish'd," or piously prayed for. What disturbs Hamlet, however, is that if death is a kind of sleep, then it might entail its own dreams, which would become a new life—these dreams are the hereafter, and the hereafter is a frightening unknown. Hamlet's hesitation is akin to that of the condemned hero Claudio in Measure for Measure, written a few years after Hamlet. "Ay, but to die," he considers, "and go we know not where;/ To lie in cold obstruction, and to rot . . ." (Act 3, scene 1). Hamlet's fear is less clearly visualized, but is of the same type. No matter how miserable life is, both heroes suppose, people prefer it to death because there's always a chance that the life after death will be worse.

THERE'S THE RUB We say "there's the rub" and think we communicate perfectly well—but do we? I mean "there's the catch" while you might think "there's the essence"—the meanings can be close, yet they're not identical. Shakespeare implies both senses, but calls up a concrete picture which would have been familiar to his audience. "Rub" is the sportsman's name for an obstacle which, in the game of bowls, diverts a ball from its true course. The Bard was obviously fond of the sport (he played on lawns, not lanes): he uses bowling analogies frequently and expertly. This is the most famous of such analogies, though not as elaborate as "Like to a bowl upon a subtle ground,/ I have tumbled past the throw" (Coriolanus, Act 5, scene 2). Although "rub" is used figuratively here, the image that leaps to Hamlet's mind is vivid and homely. Hamlet is often homely at odd moments, especially when the topic is death. "I'll lug the guts into the neighbor room" is another good example.

THIS MORTAL COIL Shakespeare is really twisting syntax with this one. "Coil" generally means a "fuss" or a "to-do"—as in the line, "for the wedding being here to-morrow, there is a great coil tonight" (Much Ado about Nothing, Act 3, scene 3). But a to-do can't be "mortal," so what Hamlet must mean is "this tumultuous world of mortals."

HIS QUIETUS MAKE WITH A BARE BODKIN This phrase succinctly illustrates the power Shakespeare can achieve by employing words with radically different origins and uses. "Quietus" is Latinate and legalistic; "bodkin" is concrete and probably Celtic in origin. Here, "his quietus make" means something like "even the balance" or "settle his accounts for good." That he might do this with a "bodkin"—elsewhere in Shakespeare a kind of knitting-needle, here a dagger—puts more menace in the abstract, almost clinical "quietus." "Fardels," "grunt," and "sweat" pick up on the grunting and sweating sound of "bodkin." "Fardel," a pack or bundle, is derived from the Arabic fardah (package): "grunt" and "sweat" are rooted in good old Anglo-Saxon. Hamlet's "fardels" are the wearying burdens of a weary life.

THE UNDISCOVERED COUNTRY, FROM WHOSE BOURN NO TRAVELLER RETURNS Comfortably back in the high diction appropriate to a noble soliloquizer, Hamlet pulls out all the stops. He may be likening the unimaginable "something after death" to the New World, from which, in this Age of Exploration, some travelers were returning and some weren't. "Bourn" literally means "limit" or "boundary"; to cross the border into the country of death, he says, is an irreversible act. But Hamlet forgets that he has had a personal conversation with one traveler who has returned—his father, whose ghost has disclosed the details of his own murder.

In other words, the question is: is it better to be alive or dead? Is it nobler to put up with all the nasty things that luck throws your way, or to fight against all those troubles by simply putting an end to them once and for all? Dying, sleeping—that’s all dying is—a sleep that ends all the heartache and shocks that life on earth gives us—that’s an achievement to wish for. To die, to sleep—to sleep, maybe to dream. Ah, but there’s the catch: in death’s sleep who knows what kind of dreams might come, after we’ve put the noise and commotion of life behind us. That’s certainly something to worry about. That’s the consideration that makes us stretch out our sufferings so long.

Hamlet "To be or not to be" - by Richard Burton

Hamlet- "To be or not to be" -Lawrence Olivier

Hamlet- "To be or not to be"- Jude Law

Hamlet's Soliloquy - "To be, or not to be" Sample Essay

Hamlet's "To be, or not to be" soliloquy is arguably the most famous soliloquy in the history of the theatre. Even today, 400 years after it was written, most people are vaguely familiar with the soliloquy even though they may not know the play. What gives these 34 lines such universal appeal and recognition? What about Hamlet's introspection has prompted scholars and theatregoers alike to ask questions about their own existence over the centuries?

In this soliloquy, Shakespeare strikes a chord with a fundamental human concern: the validity and worthiness of life. Would it not be easier for us to simply enter a never-ending sleep when we find ourselves facing the daunting problems of life than to "suffer / the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune"? However, it is perhaps because we do not know what this endless sleep entails that humans usually opt against suicide. "For in that sleep of death what dreams may come / When we have shuffled off this mortal coil / Must give us pause." Shakespeare seems to understand this dilemma through his character Hamlet, and thus the phrase "To be, or not to be" has been immortalized; indeed, it has pervaded our culture to such a remarkable extent that it has been referenced countless times in movies, television, and the media. Popular movies such as Billy Madison quote the famous phrase, and www.tobeornottobe.com serves as an online archive of Shakespeare's works. Today, a Shakespeare stereotype is held up by the bulk of society, where they see him as the god of drama, infallible and fundamentally superior to modern playwrights. However, this attitude is not new. Even centuries ago, the "holiness" of Shakespeare's work inspired and awed audiences. In a letter dated October 1, 1775, Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, commenting on David Garrick's production of Hamlet (1742-1776) to his friend Heinrich Christian Boie, likens the "To be, or not to be" soliloquy to the Lord's Prayer. He says that the soliloquy "does not naturally make the same impression on the auditor" as Hamlet's other soliloquies do,

But it produces an infinitely greater effect than could be expected of an argument on suicide and death in tragedy; and this is because a large part of the audience not only knows it by heart as well as they do the Lord's Prayer, but listens to it, so to speak, as if it were a Lord's Prayer, not indeed with the profound reflections which accompany our sacred prayer, but with a sense of solemnity and awe, of which some one who does not know England can have no conception. In this island Shakespeare is not only famous, but holy; his moral maxims are heard everywhere; I myself heard them quoted in Parliament on 7 February, a day of importance. In this way his name is entwined with most solemn thoughts; people sing of him and from his works, and thus a large number of English children know him before they have learnt their A.B.C. and creed. (Tardiff 19)

Some Scholarly Criticism

Despite the extreme popularity of Hamlet's famous soliloquy, there are some scholars who have criticized its imperfections, and even have been so bold as to say that Hamlet speaks out of character when he delivers the famous words. Tobias Smollett, a major eighteenth-century English novelist, and his contemporary Charles Gildon see the soliloquy as unnecessary in that it does not further the dramatic action of the play. Tobias Smollett writes in an essay dated 1756:

...there are an hundred characters in [Shakespeare's] plays that (if we may be allowed the expression) speak out of character. ... The famous soliloquy of Hamlet is introduced by the head and shoulders. He had some reason to revenge his father's death upon his uncle, but he had none to take away his own life. Nor does it appear from any other part of the play that he had any such intention. On the contrary, when he had a fair opportunity of being put to death in England he very wisely retorted the villainy of his conductors on their own heads. (Vickers 266-7)

In 1721, Charles Gildon bluntly writes, "That famous soliloquy which has been so much cry'd up in Hamlet has no more to do there than a description of the grove and altar of Diana, mention'd by Horace" (Vickers 369). Indeed, many think the soliloquy is out of place, and some assert that he is not contemplating suicide at all. In 1765, Samuel Johnson explains the thought, or inner monologue, of Hamlet as he delivers the soliloquy in a manner that eliminates any struggle with thoughts of suicide:

Before I can form any rational scheme of action under this pressure of distress, it is necessary to decide whether, after our present state, we are to be or not to be. That is the question which, as it shall be answered, will determine whether 'tis nobler and more suitable to the dignity of reason to suffer the outrages of fortune patiently, or to take arms against them, and by opposing end them, though perhaps with the loss of life. If to die were to sleep, no more, and by a sleep to end the miseries of our nature, such a sleep were devoutly to be wished; but if to sleep in death be to dream, to retain our powers of sensibility, we must pause to consider in that sleep of death what dreams may come. (Harris 83)

A Change in Place over Time

Whether or not you agree that the soliloquy is out of place within the play or that Hamlet speaks out of character, it is interesting to note that the placement of the soliloquy within the play has changed over time. At one point in history, Hamlet's famous soliloquy was placed earlier in the play than it is now. A year later it was changed to occur later, after Hamlet devises the play within the play. H.B. Charlton, in an essay dated 1942, explains the importance of whether the soliloquy lies before or after Hamlet devises his incriminating play:

[If] the play within the play was devised by Hamlet to give him a really necessary confirmation of the ghost's evidence, why is this the moment he chooses to utter his profoundest expression of despair, 'To be, or not to be, that is the question'? For, if his difficulty is what he says it is, this surely is the moment when the strings are all in his own hands. He has by chance found an occasion for an appropriate play, and, as the king's ready acceptance of the invitation to attend shows, he can be morally certain that the test will take place; and so, if one supposes him to need confirmation, within a trice he will really know. Yet this very situation finds him in the depths of despair. Can he really have needed the play within the play? The point is of some importance, because in the 1603 Quarto of Hamlet, this 'To be, or not to be' speech occurs before Hamlet has devised the incriminating play. In the 1604 and later versions, the speech comes where we now read it. I know no more convincing argument that the 1604 Quarto is a masterdramatist's revision of his own first draft of a play. (Harris 166)

To think or not to think...isn't this really the deeper question hamlet/shakespeare should have delve into?

without thoughts about the past, present, and future who are we...who am I really?

without the minds endless questioning, endless complaints, endless what ifs...who are we/who am i really.

Below, Tolle helps guide us on this journey to the larger self!

|

|

|