Heads up David Foster Wallace fans. Yesterday, A24 Films released a trailer for The End of the Tour, James Ponsoldt’s upcoming film which stars Jason Segel as David Foster Wallace, and Jesse Eisenberg as Rolling Stone journalist David Lipsky. The film is based on Lipsky’s 2010 memoir, Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, which documents the five-day road trip Lipsky took with Wallace in 1996, just as Wallace was completing the book tour for his breakout novel Infinite Jest.

You might know Jason Segel from lighter and often hilarious comedy films like Forgetting Sarah Marshall and Knocked Up. When The End of the Tour hits theaters on July 31st, you’ll see him inhabiting a very different kind of role.

When you’re done watching the trailer above, you can see the real David Foster Wallace in a Big, Uncut Interview recorded in 2003. It makes for an interesting comparison.

You might know Jason Segel from lighter and often hilarious comedy films like Forgetting Sarah Marshall and Knocked Up. When The End of the Tour hits theaters on July 31st, you’ll see him inhabiting a very different kind of role.

When you’re done watching the trailer above, you can see the real David Foster Wallace in a Big, Uncut Interview recorded in 2003. It makes for an interesting comparison.

As anyone who’s ever done it knows, the art of syllabussing is a fine one. (Yes, it’s a word; don’t look it up, take my word for it--Syllabussing: creating the perfect syllabus for a college-level course). It requires precision planning, stellar formatting and copy-editing skills, and near-perfect knowledge of the college-student psyche. For one, the syllabus must explain in clear terms what students can expect from the class and what the class expects from them. And it must do this without sounding so dry and pedantic that half the class drops in the first week. For another, the perfect syllabus (there’s no such thing, but one must strive) should function as both an FAQ and a contract: need to know how to format your papers? See the syllabus. Forgot when the paper was due? Too bad—see the syllabus. And so on. Most teachers learn over time that a class can stand or fall on the strength of this document.

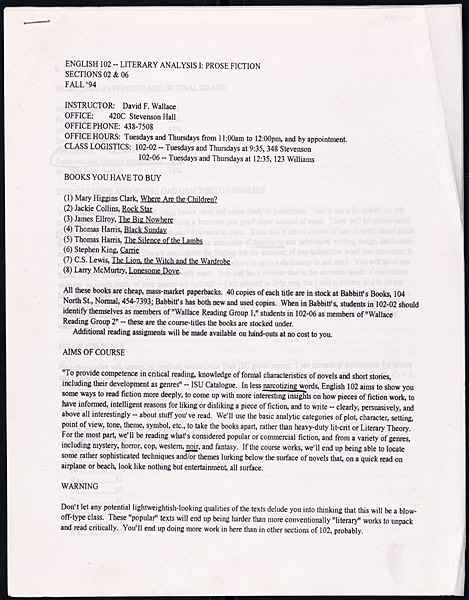

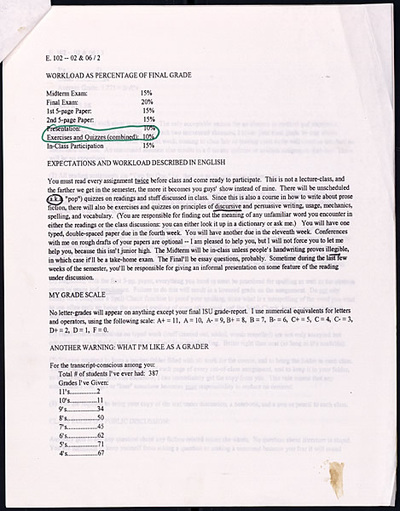

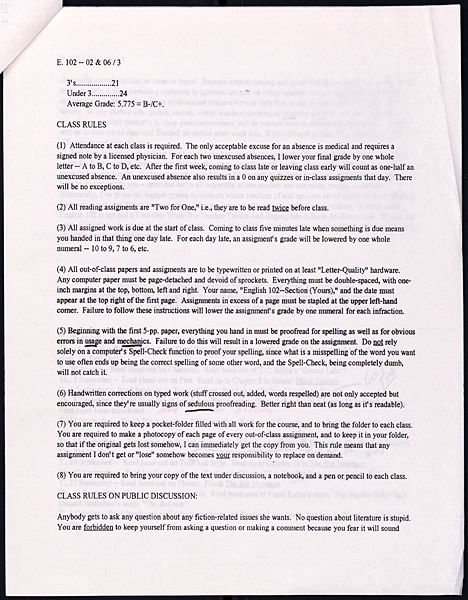

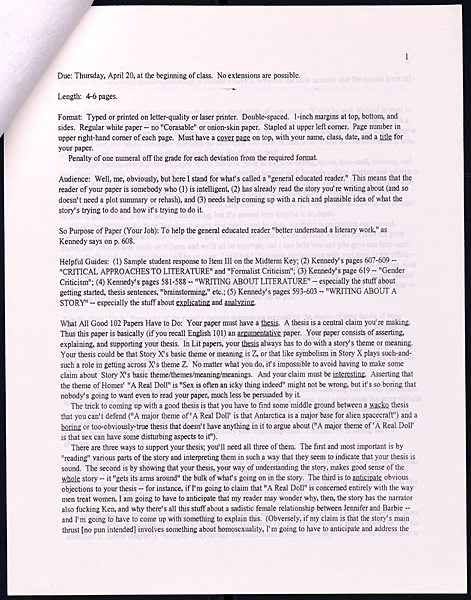

Which brings us to the syllabussing skills of one David Foster Wallace, encyclopedic literary obsessive, modern-day moralist, English professor. Love his work or hate it, it may be safe to say that Wallace was perhaps one of the most careful (or care-full) writers of his generation. And given the criteria above, you might just have to admire the fine art of his syllabi. Well, so you can, thanks to the University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center, which has scans available online of the syllabus for Wallace’s intro course “English 102-Literary Analysis: Prose Fiction” (first page above), along with other course documents. These documents—From the Fall ’94 semester at Illinois State University, where Wallace taught from 1993 to 2002—reveal the professionally pedagogical side of the literary wunderkind, a side every teacher will connect with right away.

The text in the image above is admittedly tiny (you can request higher resolution scans on the UT Austin site), but if you squint hard, you’ll see under “Aims of Course” that Wallace quotes the official ISU description of his class, then translates it into his own words:

In less narcotizing words, English 102 aims to show you some ways to read fiction more deeply, to come up with more interesting insights on how pieces of fiction work, to have informed intelligent reasons for liking or disliking a piece of fiction, and to write—clearly, persuasively, and above all interestingly—about stuff you’ve read.

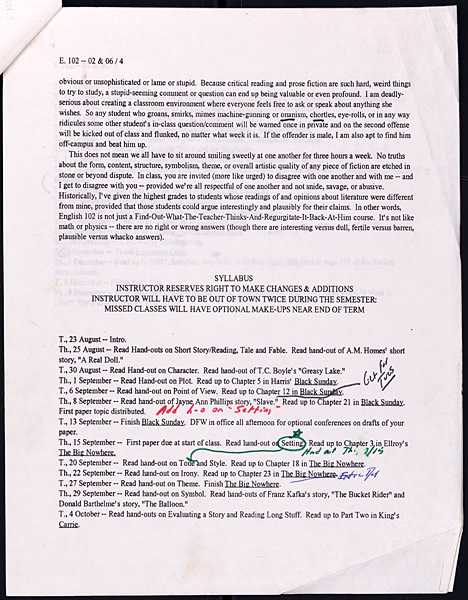

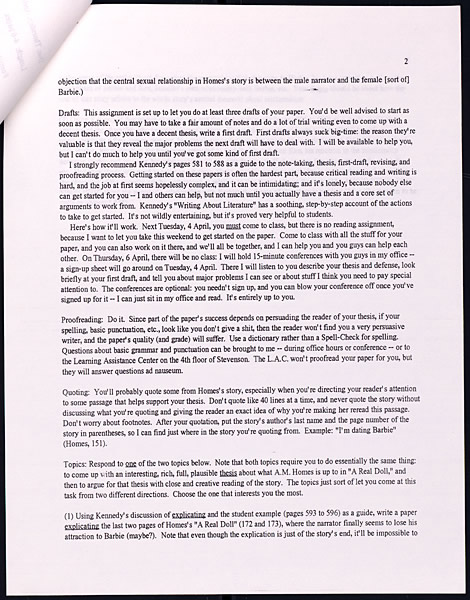

Wallace’s choice of texts is of interest as well—surprising for a writer most detractors call “pretentious.” For his class, Wallace prescribed airport-bookstore standards—what he calls “popular or commercial fiction”—such as Jackie Collins’ Rock Star, Stephen King’s Carrie, Thomas Harris’s The Silence of the Lambs, and James Elroy’s The Big Nowhere. The UT Austin site also has scans of some well-worn paperback teacher’s copies, with the red-ink marginal notes, discussion questions, and underlines one finds behind every podium. In the image above, Wallace has underlined a line of dialogue in Carrie, annotating it with the word “victim” in all-caps. Of the books Wallace requires, he writes in a section of the syllabus above called “Warning”:

Don’t let any potential lightweightish-looking qualities of the texts delude you into thinking that this will be a blow-off-type class. These “popular” texts will end up being harder than more conventionally “literary” works to unpack and read critically. You’ll end up doing more work in here than in other sections of 102, probably.

Something about that “probably” at the end grabs me (again: the precision… the college-student psyche). I admire this brave approach. Having taught conventionally “literary” stuff for years, I can say that some so-called literary fiction is formulaic in the extreme, all but containing checkboxes for the standard lit-crit categories. The commercial stuff isn’t always so careful (which is why it’s so often more fun).

UT Austin’s Harry Ransom Center houses David Foster Wallace’s library and papers, but you’ll have to make a trip to Texas (and present some academic credentials) to access most of the archive. They have scanned a few other choice pieces, however, such as the handwritten first page from a draft of his literary masterpiece/dorm-room doorstop, Infinite Jest.

Which brings us to the syllabussing skills of one David Foster Wallace, encyclopedic literary obsessive, modern-day moralist, English professor. Love his work or hate it, it may be safe to say that Wallace was perhaps one of the most careful (or care-full) writers of his generation. And given the criteria above, you might just have to admire the fine art of his syllabi. Well, so you can, thanks to the University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center, which has scans available online of the syllabus for Wallace’s intro course “English 102-Literary Analysis: Prose Fiction” (first page above), along with other course documents. These documents—From the Fall ’94 semester at Illinois State University, where Wallace taught from 1993 to 2002—reveal the professionally pedagogical side of the literary wunderkind, a side every teacher will connect with right away.

The text in the image above is admittedly tiny (you can request higher resolution scans on the UT Austin site), but if you squint hard, you’ll see under “Aims of Course” that Wallace quotes the official ISU description of his class, then translates it into his own words:

In less narcotizing words, English 102 aims to show you some ways to read fiction more deeply, to come up with more interesting insights on how pieces of fiction work, to have informed intelligent reasons for liking or disliking a piece of fiction, and to write—clearly, persuasively, and above all interestingly—about stuff you’ve read.

Wallace’s choice of texts is of interest as well—surprising for a writer most detractors call “pretentious.” For his class, Wallace prescribed airport-bookstore standards—what he calls “popular or commercial fiction”—such as Jackie Collins’ Rock Star, Stephen King’s Carrie, Thomas Harris’s The Silence of the Lambs, and James Elroy’s The Big Nowhere. The UT Austin site also has scans of some well-worn paperback teacher’s copies, with the red-ink marginal notes, discussion questions, and underlines one finds behind every podium. In the image above, Wallace has underlined a line of dialogue in Carrie, annotating it with the word “victim” in all-caps. Of the books Wallace requires, he writes in a section of the syllabus above called “Warning”:

Don’t let any potential lightweightish-looking qualities of the texts delude you into thinking that this will be a blow-off-type class. These “popular” texts will end up being harder than more conventionally “literary” works to unpack and read critically. You’ll end up doing more work in here than in other sections of 102, probably.

Something about that “probably” at the end grabs me (again: the precision… the college-student psyche). I admire this brave approach. Having taught conventionally “literary” stuff for years, I can say that some so-called literary fiction is formulaic in the extreme, all but containing checkboxes for the standard lit-crit categories. The commercial stuff isn’t always so careful (which is why it’s so often more fun).

UT Austin’s Harry Ransom Center houses David Foster Wallace’s library and papers, but you’ll have to make a trip to Texas (and present some academic credentials) to access most of the archive. They have scanned a few other choice pieces, however, such as the handwritten first page from a draft of his literary masterpiece/dorm-room doorstop, Infinite Jest.