P e r s p e c t i v e s

Differentiated Instruction/ Depth and Complexity

Thinking Tools...

Thinking Tools...

Differentiating Tools to use:

A= Who is the author (background material).

H= Humor...Something funny about the material?

He= What is the Health (Mental and Physical) of the characters?

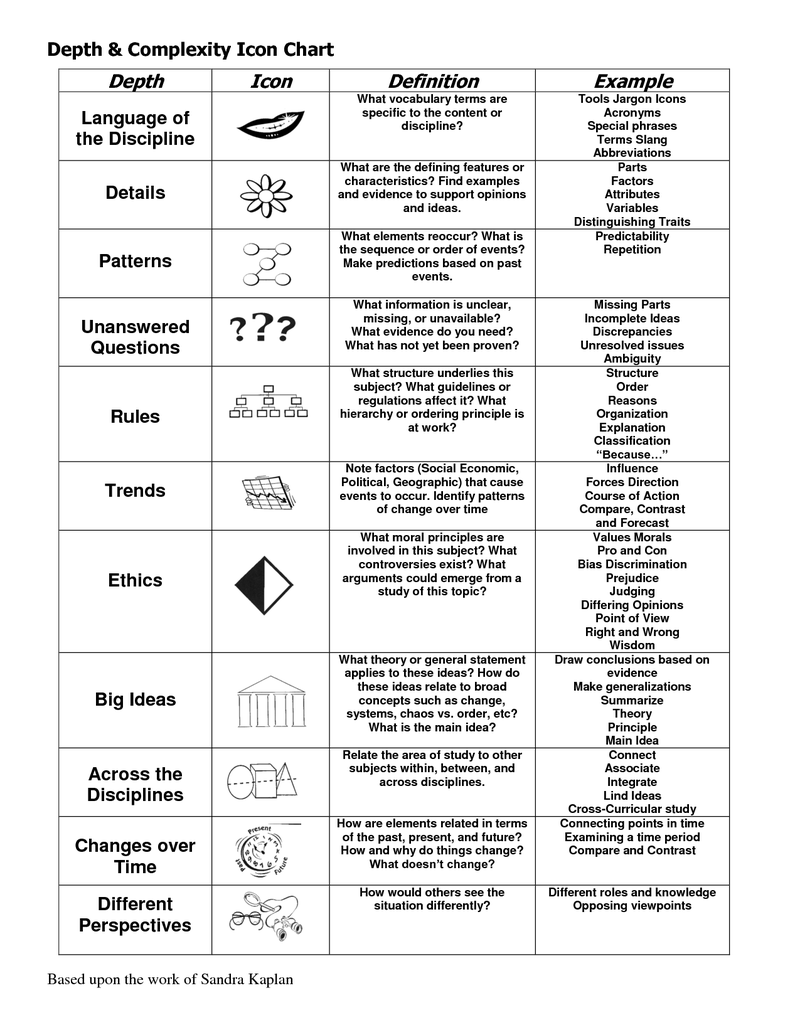

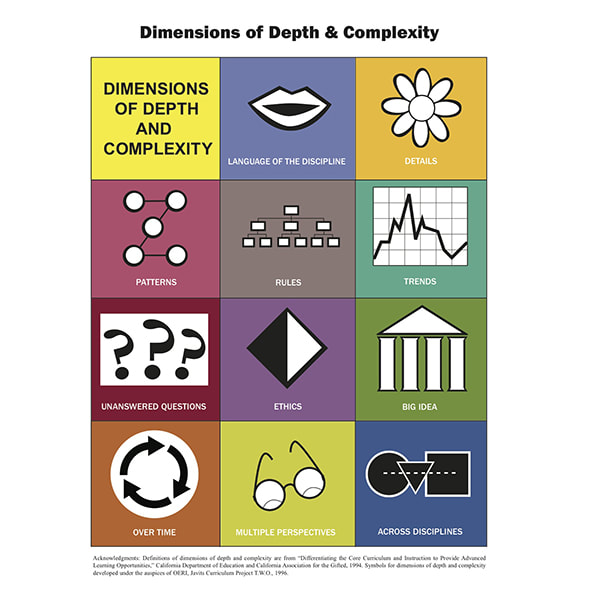

D= What are the Details?

E= Ethics (are there any ethical issues)?

P= Notice any Patterns in relationships, events, ideas, political, Etc,...?

L= What type of Language/vocabulary is used /Pragmatics means=the way a policeman/woman talks and writes?

R= Do you notice any Rules?

Tre= Trends... See any trends in the story, lecture, images, Etc,...?

B= What is the Big Picture/Context?

Time= Explain the Past, Present, and Future of the event, idea, family, or relationship?

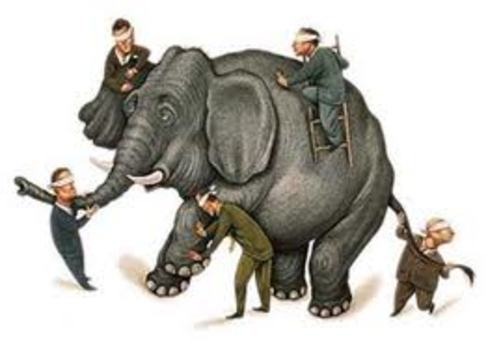

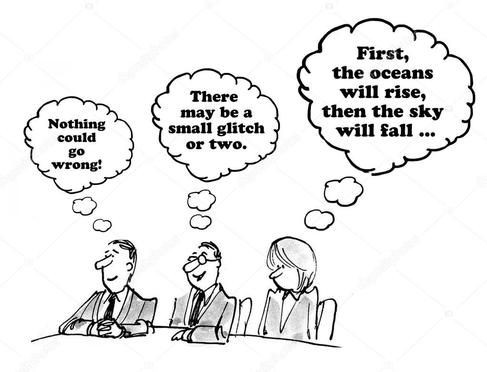

MP= Remember to look from Multiple Perspectives

AD= Look at the material from multiple Disciplines

Q= Are there any Unanswered Questions?

C= Are there any Possible Careers associated with the content?

Cult= Are there any Cultural norms you notice?

Tech= Are there Any Technology challenges seen?

V= Find a Short Video-Clip that relates to the content area...Theme...economics...politics...Etc,...?

Tools to pull from:

How does the content relate to:

Science perspectives

Economics perspectives

Art perspectives

Music perspectives

Architecture perspectives

Ethics perspectives

Gender perspectives

Social perspectives

Political perspectives

Mental and Physical Health perspectives

Historical perspectives

Philosophical perspectives

Career perspectives

Context perspectives

Themes perspectives

Motifs perspectives

Symbolism perspectives

Psychological perspectives

More Tools to Differentiate:

Origin= Where did the event originate? Place of origin?

Contribution= Who or what contributed to the event, climax, Death, Etc,...?

Paradox= Explain what the paradox's are in the story, event, Etc,...? Is there any paradox in the problem, characters, and events?

Parallel= How something is similar, matching, comparable, or analogous?

Convergence= Explain how the tendency of unrelated events helped to converge...what events/ideas came together to create the conflict?

what things came together to facilitate the conflict?

Empathy= Be able to build empathy into the reading/material/event.

A= Who is the author (background material).

H= Humor...Something funny about the material?

He= What is the Health (Mental and Physical) of the characters?

D= What are the Details?

E= Ethics (are there any ethical issues)?

P= Notice any Patterns in relationships, events, ideas, political, Etc,...?

L= What type of Language/vocabulary is used /Pragmatics means=the way a policeman/woman talks and writes?

R= Do you notice any Rules?

Tre= Trends... See any trends in the story, lecture, images, Etc,...?

B= What is the Big Picture/Context?

Time= Explain the Past, Present, and Future of the event, idea, family, or relationship?

MP= Remember to look from Multiple Perspectives

AD= Look at the material from multiple Disciplines

Q= Are there any Unanswered Questions?

C= Are there any Possible Careers associated with the content?

Cult= Are there any Cultural norms you notice?

Tech= Are there Any Technology challenges seen?

V= Find a Short Video-Clip that relates to the content area...Theme...economics...politics...Etc,...?

Tools to pull from:

How does the content relate to:

Science perspectives

Economics perspectives

Art perspectives

Music perspectives

Architecture perspectives

Ethics perspectives

Gender perspectives

Social perspectives

Political perspectives

Mental and Physical Health perspectives

Historical perspectives

Philosophical perspectives

Career perspectives

Context perspectives

Themes perspectives

Motifs perspectives

Symbolism perspectives

Psychological perspectives

More Tools to Differentiate:

Origin= Where did the event originate? Place of origin?

Contribution= Who or what contributed to the event, climax, Death, Etc,...?

Paradox= Explain what the paradox's are in the story, event, Etc,...? Is there any paradox in the problem, characters, and events?

Parallel= How something is similar, matching, comparable, or analogous?

Convergence= Explain how the tendency of unrelated events helped to converge...what events/ideas came together to create the conflict?

what things came together to facilitate the conflict?

Empathy= Be able to build empathy into the reading/material/event.

POV From:

Psychologist

Health Practitioner

Teacher

Coach

Parent

Grandparent

Lawyer

Sibling

Contractor

Musician

Sales Person

Executive

Athelite

Psychologist

Health Practitioner

Teacher

Coach

Parent

Grandparent

Lawyer

Sibling

Contractor

Musician

Sales Person

Executive

Athelite

Consequence..........Outcome; result; effect; what was changed?

Possibility................Something that could occur in the future

Reaction...................Action in response to something that happens

Motivation.................Something the prompts an action

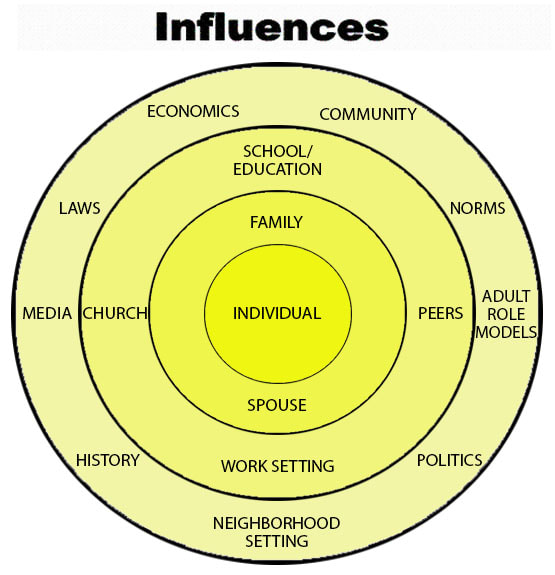

Influence....................The power to cause an effect; to sway or persuade

Condition...................how something is or lives; relevant circumstances

Significance...............The quality of being important

Value.........................Relative worth, merit or importance

Importance................Value in content, worth or relationship

Kind............................A group united by a common characteristic

Type............................A group distinguished by some particular trait

Trait............................distinguishing characteristics

Characteristic...............Distinguishing feature or quality

Function......................How something is works or is used

Reason........................Justification for belief, act or action

Rationale....................An explanation of the fundamental reasons

Evidence.....................an outward sign or indication; proof

Purpose......................The reason for being; objective to be achieved

Relevance..................Pertinent/Important to the matter at hand; applicable

Possibility................Something that could occur in the future

Reaction...................Action in response to something that happens

Motivation.................Something the prompts an action

Influence....................The power to cause an effect; to sway or persuade

Condition...................how something is or lives; relevant circumstances

Significance...............The quality of being important

Value.........................Relative worth, merit or importance

Importance................Value in content, worth or relationship

Kind............................A group united by a common characteristic

Type............................A group distinguished by some particular trait

Trait............................distinguishing characteristics

Characteristic...............Distinguishing feature or quality

Function......................How something is works or is used

Reason........................Justification for belief, act or action

Rationale....................An explanation of the fundamental reasons

Evidence.....................an outward sign or indication; proof

Purpose......................The reason for being; objective to be achieved

Relevance..................Pertinent/Important to the matter at hand; applicable

Sample Focused Learning Targets using Differentiated Instruction:

FLTs

Students, today we will discuss what result did the main character's behavior have on......?

Students, today we are going to examine how the main character Stepmother, Daughters, Cinderella, contribute to the conflict in the story?

Students, today we are going to examine the details in the story, The Giving Tree to determine how the boy changed over time.

Students, today we are going to examine the details of the California Gold Rush and how expectations for children have changed over time.

Students, today we are going to examine the ethical issues surrounding the gold rush from different cultural perspectives (American, Irish, Italian,...).

Students, today we are going to analyze the conflict in the story, Jack and the beanstalk from the perspectives of both Jack and the Giant.

Students, today we are going to analyze the details in the story, "The Paper Bag Princess" from the perspective of both Elizabeth and Ronald.

FLTs

Students, today we will discuss what result did the main character's behavior have on......?

Students, today we are going to examine how the main character Stepmother, Daughters, Cinderella, contribute to the conflict in the story?

Students, today we are going to examine the details in the story, The Giving Tree to determine how the boy changed over time.

Students, today we are going to examine the details of the California Gold Rush and how expectations for children have changed over time.

Students, today we are going to examine the ethical issues surrounding the gold rush from different cultural perspectives (American, Irish, Italian,...).

Students, today we are going to analyze the conflict in the story, Jack and the beanstalk from the perspectives of both Jack and the Giant.

Students, today we are going to analyze the details in the story, "The Paper Bag Princess" from the perspective of both Elizabeth and Ronald.

Differentiating for Tweens

by Rick Wormeli

Teaching tweens requires special skills—and the willingness to do whatever it takes to ensure student success.

Effective instruction for 12-year-olds looks different from effective instruction for 8-year-olds or 17-year-olds. Combine the developmental needs of typical tweens and the wildly varying needs of individuals within this age group, and you can see that flourishing as a middle-grades teacher requires special skills.

It's not as overwhelming as it sounds, however. There are some commonsense basics that serve students well. The five strategies described here revolve around the principles of differentiated instruction, which does not always involve individualized instruction. Teachers who differentiate instruction simply do what's fair and developmentally appropriate for students when the “regular” instruction doesn't meet their needs.

Strategy 1:

Teach to Developmental NeedsReports from the Carnegie Corporation (Jackson & Davis, 2000) and the National Middle School Association (2003), as well as the expertise of veteran middle school teachers, point to seven conditions that young adolescents crave: competence and achievement; opportunities for self-definition; creative expression; physical activity; positive social interactions with adults and peers; structure and clear limits; and meaningful participation in family, school, and community. No matter how creatively we teach—and no matter how earnestly we engage in differentiated instruction, authentic assessment, and character education—the effects will be significantly muted if we don't create an environment that responds to students' developmental needs. Different students will require different degrees of attention regarding each of these factors.

Take tweens' need for physical movement. It's not enough for tweens to move between classes every 50 minutes (or every 80 minutes on a block schedule). Effective tween instruction incorporates movement every 10 to 15 minutes. So we ask all students to get up and walk across the room to turn in their papers, not just have one student collect the papers while the rest of them sit passively. We let students process information physically from time to time: for example, by using the ceiling as a massive, organizer matrix and asking students to hold cards with information for each matrix cell and stand under the proper location as indicated on the ceiling. We use flexible grouping, which allows students to move about the room to work with different partners.

Every topic in the curriculum can be turned into a physical experience, even if it's very abstract. We can do this for some or all of our students as needed. We can use simulations, manipulatives, body statues (frozen tableau), and finger plays to portray irony, metabolism, chromatic scale, republics, qualitative analysis, grammar, and multiplying binomials (Glynn, 2001; Wormeli, 2005). These aren't “fluff” activities; they result in real learning for this age group.

To address students' need for self-definition, we give them choices in school projects. We help students identify consequences for the academic and personal decisions they make. We also teach students about their own learning styles. We put students in positions of responsibility in our schools and communities that allow them to make positive contributions and earn recognition for doing so. We provide clear rules and enforce them calmly—even if it's the umpteenth time that day that we've needed to enforce the same rule—to help students learn to function as members of a civilized society.

Integrating developmental needs into tweens' learning is nonnegotiable. It's not something teachers do only if we have time in the schedule; it's vital to tween success. As teachers of this age group, we need to apply our adolescent development expertise in every interaction. If we don't, the lesson will fall flat and even worse, students will wither.

Strategy 2:

Treat Academic Struggle as StrengthYoung adolescents readily identify differences and similarities among themselves, and in their efforts to belong to particular groups, they can be judgmental about classmates' learning styles or progress (Jackson & Davis, 2000). At this junction, then, it's important to show students that not everyone starts at the same point along the learning continuum or learns in the same way. Some classmates learn content by drawing it, others by writing about it, and still others by discussing it—and even the best students are beginners in some things.

Unfortunately, students in nondifferentiated classes often view cultural and academic differences as signs of weakness and inferiority. Good students in these classes often try to protect their reputations as being the kids who always get the problems right or finish first. They rarely take chances and stretch themselves for fear of faltering in front of others. This approach to learning rarely leads to success in high school and beyond.

Educators of tweens need to make academic struggle virtuous. So we model asking difficult questions to which we don't know the answers, and we publicly demonstrate our journey to answer those questions. We affirm positive risk taking in homework as well as the knowledge gained through science experiments that fail. We push students to explore their undeveloped skills without fear of grade repercussions, and we frequently help students see the growth they've made over time.

In one of my classes, Jared was presenting an oral report on Aristotle's rhetorical triangle (ethos, pathos, logos), and he was floundering. Embarrassed because he kept forgetting his memorized speech, he begged me to let him take an F and sit down. Instead, I asked Jared to take a few deep breaths and try again. He did, but again, he bombed. I explained that an oral report is not just about delivering information; it's also about taking risks and developing confidence. “We're all beginners at one point, Jared,” I explained:

This is your time to be a beginner. The worst that can happen is that you learn from the experience and have to do it again. That's not too bad.

After his classmates offered encouraging comments, Jared tried a third time and got a little farther before stopping his speech. I suggested that he repeat the presentation in short segments, resting between each one. He tried it, and it worked. After Jared finished, he moved to take his seat, but I stopped him and asked him to repeat the entire presentation, this time without rests.

As his classmates grinned and nodded, Jared returned to the front of the room. This time, he made it through his presentation without a mistake. His classmates applauded. Jared bowed, smiled, and took his seat. His eyes watered a bit when he looked at me. Adrenalin can do that to a guy, but I hoped it was more. Everyone learned a lot about tenacity that day, and Jared took his first steps toward greater confidence (Wormeli, 1999).

Strategy 3:

Provide Multiple Pathways to StandardsDifferentiation requires us to invite individual students to acquire, process, and demonstrate knowledge in ways different from the majority of the class if that's what they need to become proficient. When we embrace this approach, we give more than one example and suggest more than one strategy. We teach students eight different ways to take notes, not just one, and then help them decide when to use each technique. We let students use wide- or college-ruled paper, and we guide them in choosing multiple single-subject folders or one large binder for all subjects—whichever works best for them.

We don't limit students' exposure to sophisticated thinking because they have not yet mastered the basics. Tweens are capable of understanding how to solve for a variable or graph an inequality even if they struggle with the negative/positive signs when multiplying integers. We can teach a global lesson on a sophisticated concept for 15 minutes, and then allow students to process the information in groups tiered for different levels of readiness—or we can present an anchor activity for the whole class to do while we pull out subgroups for minilessons on the basics or on advanced material. Our goal is to respond to the unique students in front of us as we make learning coherent for all.

In the area of assessment, we should never let the test format get in the way of a student's ability to reveal what he or she knows and is able to do. For example, if an assessment on Ben Mikaelsen's novel Touching Spirit Bear (Harper Trophy, 2002) required students to create a poster showing the development of characters in the story, it would necessarily assess artistic skill in addition to assessing the students' understanding of the novel. Students with poor artistic skills would be unable to reveal the full extent of what they know. Consequently, we allow students to select alternative assessments through which they can more accurately portray their mastery.

In differentiated classes, grading focuses on clear and consistent evidence of mastery, not on the medium through which the student demonstrates that mastery. For example, we may give students five different choices for showing what they know about the rise of democracy: writing a report, designing a Web site, building a library display, transcribing a “live” interview with a historical figure, or creating a series of podcasts simulating a discussion between John Locke and Thomas Jefferson about where governments get their authority. We can grade all the projects using a common scoring rubric that contains the universal standards for which we're holding students accountable.

In 2001, 40.7 percent of students in grades 3–5 and 41.7 percent of students in grades 6–8 participated in after-school activities (such as school sports, religious activities, scouts, and clubs) on a weekly basis.

—NCES, The Condition of Education 2004

Of course, if the test format is the assessment, we don't allow students to opt for something else. For example, when we ask students to write a well-crafted persuasive essay, they can't instead choose to write a persuasive dialogue or create a poster. Even then, however, we can differentiate the pace of instruction and be flexible about the time required for student mastery. Just as we would never demand that all humans be able to recite the alphabet fluently on the first Monday after their 3rd birthday, it goes against all we know about teaching tweens to mandate that all students master slope and y-intercept during the first week of October in grade 7.

Thus, we allow tweens to redo work and assessments until they master the content, and we give them full credit for doing so. Our job is to teach students the material, not to document how they've failed. We never want to succumb to what middle-grades expert Nancy Doda calls the “learn or I will hurt you” mentality by demanding that all students learn at the same pace and in the same manner as their classmates and giving them only one chance to succeed.

Strategy 4:

Give Formative Feedback...Tweens don't always know when they don't know, and they don't always know when they do. One of the most helpful strategies we can employ is to provide frequent formative feedback. Tween learning tends to be more multilayered and episodic than linear; continual assessment and feedback correct misconceptions before they take root. Tweens learn more when teachers take off the evaluation hat and hold up a mirror to students, helping them compare what they did with what they were supposed to have done.

Because learning and motivation can be fragile at this age, we have to find ways to provide that feedback promptly. We do this by giving students short assignments—such as one-page writings instead of multipage reports—that we can evaluate and return in a timely manner. When we formally assess student writing, we focus on just one or two areas so that students can assimilate our feedback.

To get a quick read on students' understanding of a particular lesson, we can use exit card activities, which are quick products created by students in response to prompts. For example, at the end of a U.S. history lesson, we might ask, “Using what we've learned today, make a Venn diagram that compares and contrasts World Wars I and II.” The 3-2-1 exit card format can yield rich information (Wormeli, 2005). Here are two examples:

3—Identify three characteristic ways Renaissance art differs from medieval art.

2—List two important scientific debates that occurred during the Renaissance.

1—Provide one good reason why rebirth is an appropriate term to describe the Renaissance.

3—Identify at least three differences between acids and bases.

2—List one use of an acid and one use of a base.

1—State one reason why knowledge of acids and bases is important to citizens in our community.

Strategy 5:

Dare to Be UnconventionalCurriculum theorists have often referred to early adolescence as the age of romanticism: Tweens are interested in that which is novel, compels them, and appeals to their curiosity about the world (Pinar, Reynolds, Slattery, & Taubman, 2000). To successfully teach tweens, we have to be willing to transcend convention once in a while. It's not a lark; it's essential.

Being unconventional means we occasionally teach math algorithms by giving students the answers to problems and asking them how those answers were derived. We improve student word savvy by asking students to conduct an intelligent conversation without using verbs. (They can't; they sound like Tarzan.) We ask students to teach some lessons, with the principal or a parent as coteacher. Students can make a video for 4th graders on the three branches of government, convey Aristotle's rhetorical triangle by juggling tennis balls, or correspond with adult astronomers about their study of the planets. They can create literary magazines of science, math, or health writing that will end up in local dentist offices and Jiffy Lube shops. They can learn about the Renaissance through a “Meeting of Minds” debate in which they portray Machiavelli, da Vinci, Erasmus, Luther, Calvin, and Henry VIII. The power of such lessons lies in their substance and novelty, and young adolescents are acutely attuned to these qualities.

Ninety percent of what we do with young adolescents is quiet, behind-the-scenes facilitation. Ten percent, however, is an inspired dog and pony show without apologies. At this “I dare you to show me something I don't know” and “Shake me out of my self-absorption” age, being unconventional is key.

Thus, when my students were confusing the concepts of adjective and adverb, I did the most professional thing I could think of: I donned tights, shorts, a cape, and a mask, and became Adverb Man. I moved through the hallways handing out index cards with adverbs written on them. “You need to move quickly,” I said, handing a student late to class a card on which the word quickly was written. “You need to move now,” I said to another, handing him a card with the adverb on it. Once in a while, I'd raise my voice, Superman-style, and declare, “Remember, good citizens of Earth, what Adverb Man always says: ‘Up, up, and modify adverbs, verbs, and adjectives!’” The next day, one of the girls on our middle school team came walking down the hallway to my classroom dressed as Pronoun Girl. One of her classmates preceded her—he was dressed as Antecedent Boy. Both wore yellow masks and had long beach towels tucked into the backs of their shirt collars as capes. Pronoun Girl had taped pronouns across her shirt that corresponded with the nouns taped across Antecedent Boy's shirt.

It was better than Schoolhouse Rock. And the best part? There wasn't any grade lower than a B+ on the adverbs test that Friday (Wormeli, 2001).

Navigating the Tween RiverOf all the states of matter in the known universe, tweens most closely resemble liquid. Students at this age have a defined volume, but not a defined shape. They are ever ready to flow, and they are rarely compressible. Although they can spill, freeze, and boil, they can also lift others, do impressive work, take the shape of their environment, and carry multiple ideas within themselves. Some teachers argue that dark matter is a better analogy—but those are teachers trying to keep order during the last period on a Friday.

Imagine directing the course of a river that flows through a narrow, ever-changing channel toward a greater purpose yet to be discovered, and you have the basics of teaching tweens. To chart this river's course, we must be experts in the craft of guiding young, fluid adolescents in their pressure-filled lives, and we must adjust our methods according to the flow, volume, and substrate within each student. It's a challenging river to navigate, but worth the journey.

The Day I Was Caught Plagiarizing/Hijacking

Young adolescents are still learning what is moral and how to act responsibly. I decided to help them along.

One day, I shared a part of an education magazine column with my 7th grade students. I told them that I wrote it and was seeking their critique before submitting it for publishing. In reality, the material I shared was an excerpt from a book written by someone else. I was hiding the book behind a notebook from which I read.

A parent coconspirator was in the classroom for the period, pretending to observe the lesson. While I read the piece that I claimed as my own, the parent acted increasingly uncomfortable. Finally, she interrupted me and said that she just couldn't let me go on. She had read the exact ideas that I claimed as my own in another book. I assured her that she was confused, and I continued.

She interrupted me again, this time angrily. She said she was not confused and named the book from which I was reading, having earlier received the information from me in our preclass set-up. At this point, I let myself appear more anxious about her words. Her concern grew, and she persisted in her comments until I finally admitted that I hadn't written the material. Acting ashamed, I revealed the book to the class. The kids' mouths opened, some in confused grins, some greatly concerned, not knowing what to believe.

The parent let me have it then. She reminded me that I was in a position of trust as a teacher—how dare I break that trust! She said that I was being a terrible role model and that my students would never again trust my writings or teaching. She declared that this was a breach of professional conduct and that my principal would be informed. Throughout all of this, I countered her points with the excuses that students often make when caught plagiarizing: It's only a small part. The rest of the writing is original; what does it matter that this one part was written by someone else? I've never done it before, and I'm not ever going to do it again, so it's not that bad.

The students' faces dissolved into disbelief, some into anger. Students vicariously experienced the uncomfortable feeling of being trapped in a lie and having one's reputation impugned. At the height of the emotional tension between the parent and me, I paused and asked the students, “Have you had enough?” With a smile and a thank-you to the parent assistant, I asked how many folks would like to learn five ways not to plagiarize material; then I went to the chalkboard.

Students breathed a sigh of relief. Notebooks flew onto desktops, and pens raced across paper to get down everything I taught for the rest of class; they hung on every word. Students wanted to do anything to avoid the “yucky” feelings associated with plagiarism that they had experienced moments ago. I taught them ways to cite sources, how to paraphrase another's words, and how many words from an original source we could use before we were lifting too much. We discussed the legal ramifications of plagiarism. Later, we applauded the acting talent of our parent assistant.

One student in the room that day reflected on this lesson at the end of the year:

I know I'll never forget when my teacher got “caught” plagiarizing. The sensations were simply too real.... Although my teacher is extremely moral, it was frightening how close to home it struck. The moment when my teacher admitted it, the room fell silent. It was awful. All my life, teachers have preached about plagiarism, and it never really sank in. But when you actually experience it, it's a whole different story.

To this day, students visit me from high school and college and say, “I was tempted to plagiarize this one little bit on one of my papers, but I didn't because I remembered how mad I was at you.” That's a teacher touchdown.

—Rick Wormeli

ReferencesGlynn, C. (2001). Learning on their feet. Shoreham, VT: Discover Writing Press.

Jackson, A., & Davis, G. (2000). Turning points 2000: Educating adolescents in the 21st century. New York: Carnegie Corporation.

National Middle School Association. (2003). This we believe: Successful schools for young adolescents. Westerville, OH: Author.

Pinar, W. F., Reynolds, W. M., Slattery, P., & Taubman, P. M. (2000). Understanding curriculum. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Wormeli, R. (1999). The test of accountability in middle school. Middle Ground, 3(7), 17–18, 53.

Wormeli, R. (2001). Meet me in the middle. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.

Wormeli, R. (2005). Summarization in any subject: 50 techniques to improve student learning. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Rick Wormeli (703-620-2447; [email protected]) taught young adolescents for 25 years. He is now a consultant who works with administrators and teachers across the United States. He resides in Herndon, Virginia.

by Rick Wormeli

Teaching tweens requires special skills—and the willingness to do whatever it takes to ensure student success.

Effective instruction for 12-year-olds looks different from effective instruction for 8-year-olds or 17-year-olds. Combine the developmental needs of typical tweens and the wildly varying needs of individuals within this age group, and you can see that flourishing as a middle-grades teacher requires special skills.

It's not as overwhelming as it sounds, however. There are some commonsense basics that serve students well. The five strategies described here revolve around the principles of differentiated instruction, which does not always involve individualized instruction. Teachers who differentiate instruction simply do what's fair and developmentally appropriate for students when the “regular” instruction doesn't meet their needs.

Strategy 1:

Teach to Developmental NeedsReports from the Carnegie Corporation (Jackson & Davis, 2000) and the National Middle School Association (2003), as well as the expertise of veteran middle school teachers, point to seven conditions that young adolescents crave: competence and achievement; opportunities for self-definition; creative expression; physical activity; positive social interactions with adults and peers; structure and clear limits; and meaningful participation in family, school, and community. No matter how creatively we teach—and no matter how earnestly we engage in differentiated instruction, authentic assessment, and character education—the effects will be significantly muted if we don't create an environment that responds to students' developmental needs. Different students will require different degrees of attention regarding each of these factors.

Take tweens' need for physical movement. It's not enough for tweens to move between classes every 50 minutes (or every 80 minutes on a block schedule). Effective tween instruction incorporates movement every 10 to 15 minutes. So we ask all students to get up and walk across the room to turn in their papers, not just have one student collect the papers while the rest of them sit passively. We let students process information physically from time to time: for example, by using the ceiling as a massive, organizer matrix and asking students to hold cards with information for each matrix cell and stand under the proper location as indicated on the ceiling. We use flexible grouping, which allows students to move about the room to work with different partners.

Every topic in the curriculum can be turned into a physical experience, even if it's very abstract. We can do this for some or all of our students as needed. We can use simulations, manipulatives, body statues (frozen tableau), and finger plays to portray irony, metabolism, chromatic scale, republics, qualitative analysis, grammar, and multiplying binomials (Glynn, 2001; Wormeli, 2005). These aren't “fluff” activities; they result in real learning for this age group.

To address students' need for self-definition, we give them choices in school projects. We help students identify consequences for the academic and personal decisions they make. We also teach students about their own learning styles. We put students in positions of responsibility in our schools and communities that allow them to make positive contributions and earn recognition for doing so. We provide clear rules and enforce them calmly—even if it's the umpteenth time that day that we've needed to enforce the same rule—to help students learn to function as members of a civilized society.

Integrating developmental needs into tweens' learning is nonnegotiable. It's not something teachers do only if we have time in the schedule; it's vital to tween success. As teachers of this age group, we need to apply our adolescent development expertise in every interaction. If we don't, the lesson will fall flat and even worse, students will wither.

Strategy 2:

Treat Academic Struggle as StrengthYoung adolescents readily identify differences and similarities among themselves, and in their efforts to belong to particular groups, they can be judgmental about classmates' learning styles or progress (Jackson & Davis, 2000). At this junction, then, it's important to show students that not everyone starts at the same point along the learning continuum or learns in the same way. Some classmates learn content by drawing it, others by writing about it, and still others by discussing it—and even the best students are beginners in some things.

Unfortunately, students in nondifferentiated classes often view cultural and academic differences as signs of weakness and inferiority. Good students in these classes often try to protect their reputations as being the kids who always get the problems right or finish first. They rarely take chances and stretch themselves for fear of faltering in front of others. This approach to learning rarely leads to success in high school and beyond.

Educators of tweens need to make academic struggle virtuous. So we model asking difficult questions to which we don't know the answers, and we publicly demonstrate our journey to answer those questions. We affirm positive risk taking in homework as well as the knowledge gained through science experiments that fail. We push students to explore their undeveloped skills without fear of grade repercussions, and we frequently help students see the growth they've made over time.

In one of my classes, Jared was presenting an oral report on Aristotle's rhetorical triangle (ethos, pathos, logos), and he was floundering. Embarrassed because he kept forgetting his memorized speech, he begged me to let him take an F and sit down. Instead, I asked Jared to take a few deep breaths and try again. He did, but again, he bombed. I explained that an oral report is not just about delivering information; it's also about taking risks and developing confidence. “We're all beginners at one point, Jared,” I explained:

This is your time to be a beginner. The worst that can happen is that you learn from the experience and have to do it again. That's not too bad.

After his classmates offered encouraging comments, Jared tried a third time and got a little farther before stopping his speech. I suggested that he repeat the presentation in short segments, resting between each one. He tried it, and it worked. After Jared finished, he moved to take his seat, but I stopped him and asked him to repeat the entire presentation, this time without rests.

As his classmates grinned and nodded, Jared returned to the front of the room. This time, he made it through his presentation without a mistake. His classmates applauded. Jared bowed, smiled, and took his seat. His eyes watered a bit when he looked at me. Adrenalin can do that to a guy, but I hoped it was more. Everyone learned a lot about tenacity that day, and Jared took his first steps toward greater confidence (Wormeli, 1999).

Strategy 3:

Provide Multiple Pathways to StandardsDifferentiation requires us to invite individual students to acquire, process, and demonstrate knowledge in ways different from the majority of the class if that's what they need to become proficient. When we embrace this approach, we give more than one example and suggest more than one strategy. We teach students eight different ways to take notes, not just one, and then help them decide when to use each technique. We let students use wide- or college-ruled paper, and we guide them in choosing multiple single-subject folders or one large binder for all subjects—whichever works best for them.

We don't limit students' exposure to sophisticated thinking because they have not yet mastered the basics. Tweens are capable of understanding how to solve for a variable or graph an inequality even if they struggle with the negative/positive signs when multiplying integers. We can teach a global lesson on a sophisticated concept for 15 minutes, and then allow students to process the information in groups tiered for different levels of readiness—or we can present an anchor activity for the whole class to do while we pull out subgroups for minilessons on the basics or on advanced material. Our goal is to respond to the unique students in front of us as we make learning coherent for all.

In the area of assessment, we should never let the test format get in the way of a student's ability to reveal what he or she knows and is able to do. For example, if an assessment on Ben Mikaelsen's novel Touching Spirit Bear (Harper Trophy, 2002) required students to create a poster showing the development of characters in the story, it would necessarily assess artistic skill in addition to assessing the students' understanding of the novel. Students with poor artistic skills would be unable to reveal the full extent of what they know. Consequently, we allow students to select alternative assessments through which they can more accurately portray their mastery.

In differentiated classes, grading focuses on clear and consistent evidence of mastery, not on the medium through which the student demonstrates that mastery. For example, we may give students five different choices for showing what they know about the rise of democracy: writing a report, designing a Web site, building a library display, transcribing a “live” interview with a historical figure, or creating a series of podcasts simulating a discussion between John Locke and Thomas Jefferson about where governments get their authority. We can grade all the projects using a common scoring rubric that contains the universal standards for which we're holding students accountable.

In 2001, 40.7 percent of students in grades 3–5 and 41.7 percent of students in grades 6–8 participated in after-school activities (such as school sports, religious activities, scouts, and clubs) on a weekly basis.

—NCES, The Condition of Education 2004

Of course, if the test format is the assessment, we don't allow students to opt for something else. For example, when we ask students to write a well-crafted persuasive essay, they can't instead choose to write a persuasive dialogue or create a poster. Even then, however, we can differentiate the pace of instruction and be flexible about the time required for student mastery. Just as we would never demand that all humans be able to recite the alphabet fluently on the first Monday after their 3rd birthday, it goes against all we know about teaching tweens to mandate that all students master slope and y-intercept during the first week of October in grade 7.

Thus, we allow tweens to redo work and assessments until they master the content, and we give them full credit for doing so. Our job is to teach students the material, not to document how they've failed. We never want to succumb to what middle-grades expert Nancy Doda calls the “learn or I will hurt you” mentality by demanding that all students learn at the same pace and in the same manner as their classmates and giving them only one chance to succeed.

Strategy 4:

Give Formative Feedback...Tweens don't always know when they don't know, and they don't always know when they do. One of the most helpful strategies we can employ is to provide frequent formative feedback. Tween learning tends to be more multilayered and episodic than linear; continual assessment and feedback correct misconceptions before they take root. Tweens learn more when teachers take off the evaluation hat and hold up a mirror to students, helping them compare what they did with what they were supposed to have done.

Because learning and motivation can be fragile at this age, we have to find ways to provide that feedback promptly. We do this by giving students short assignments—such as one-page writings instead of multipage reports—that we can evaluate and return in a timely manner. When we formally assess student writing, we focus on just one or two areas so that students can assimilate our feedback.

To get a quick read on students' understanding of a particular lesson, we can use exit card activities, which are quick products created by students in response to prompts. For example, at the end of a U.S. history lesson, we might ask, “Using what we've learned today, make a Venn diagram that compares and contrasts World Wars I and II.” The 3-2-1 exit card format can yield rich information (Wormeli, 2005). Here are two examples:

3—Identify three characteristic ways Renaissance art differs from medieval art.

2—List two important scientific debates that occurred during the Renaissance.

1—Provide one good reason why rebirth is an appropriate term to describe the Renaissance.

3—Identify at least three differences between acids and bases.

2—List one use of an acid and one use of a base.

1—State one reason why knowledge of acids and bases is important to citizens in our community.

Strategy 5:

Dare to Be UnconventionalCurriculum theorists have often referred to early adolescence as the age of romanticism: Tweens are interested in that which is novel, compels them, and appeals to their curiosity about the world (Pinar, Reynolds, Slattery, & Taubman, 2000). To successfully teach tweens, we have to be willing to transcend convention once in a while. It's not a lark; it's essential.

Being unconventional means we occasionally teach math algorithms by giving students the answers to problems and asking them how those answers were derived. We improve student word savvy by asking students to conduct an intelligent conversation without using verbs. (They can't; they sound like Tarzan.) We ask students to teach some lessons, with the principal or a parent as coteacher. Students can make a video for 4th graders on the three branches of government, convey Aristotle's rhetorical triangle by juggling tennis balls, or correspond with adult astronomers about their study of the planets. They can create literary magazines of science, math, or health writing that will end up in local dentist offices and Jiffy Lube shops. They can learn about the Renaissance through a “Meeting of Minds” debate in which they portray Machiavelli, da Vinci, Erasmus, Luther, Calvin, and Henry VIII. The power of such lessons lies in their substance and novelty, and young adolescents are acutely attuned to these qualities.

Ninety percent of what we do with young adolescents is quiet, behind-the-scenes facilitation. Ten percent, however, is an inspired dog and pony show without apologies. At this “I dare you to show me something I don't know” and “Shake me out of my self-absorption” age, being unconventional is key.

Thus, when my students were confusing the concepts of adjective and adverb, I did the most professional thing I could think of: I donned tights, shorts, a cape, and a mask, and became Adverb Man. I moved through the hallways handing out index cards with adverbs written on them. “You need to move quickly,” I said, handing a student late to class a card on which the word quickly was written. “You need to move now,” I said to another, handing him a card with the adverb on it. Once in a while, I'd raise my voice, Superman-style, and declare, “Remember, good citizens of Earth, what Adverb Man always says: ‘Up, up, and modify adverbs, verbs, and adjectives!’” The next day, one of the girls on our middle school team came walking down the hallway to my classroom dressed as Pronoun Girl. One of her classmates preceded her—he was dressed as Antecedent Boy. Both wore yellow masks and had long beach towels tucked into the backs of their shirt collars as capes. Pronoun Girl had taped pronouns across her shirt that corresponded with the nouns taped across Antecedent Boy's shirt.

It was better than Schoolhouse Rock. And the best part? There wasn't any grade lower than a B+ on the adverbs test that Friday (Wormeli, 2001).

Navigating the Tween RiverOf all the states of matter in the known universe, tweens most closely resemble liquid. Students at this age have a defined volume, but not a defined shape. They are ever ready to flow, and they are rarely compressible. Although they can spill, freeze, and boil, they can also lift others, do impressive work, take the shape of their environment, and carry multiple ideas within themselves. Some teachers argue that dark matter is a better analogy—but those are teachers trying to keep order during the last period on a Friday.

Imagine directing the course of a river that flows through a narrow, ever-changing channel toward a greater purpose yet to be discovered, and you have the basics of teaching tweens. To chart this river's course, we must be experts in the craft of guiding young, fluid adolescents in their pressure-filled lives, and we must adjust our methods according to the flow, volume, and substrate within each student. It's a challenging river to navigate, but worth the journey.

The Day I Was Caught Plagiarizing/Hijacking

Young adolescents are still learning what is moral and how to act responsibly. I decided to help them along.

One day, I shared a part of an education magazine column with my 7th grade students. I told them that I wrote it and was seeking their critique before submitting it for publishing. In reality, the material I shared was an excerpt from a book written by someone else. I was hiding the book behind a notebook from which I read.

A parent coconspirator was in the classroom for the period, pretending to observe the lesson. While I read the piece that I claimed as my own, the parent acted increasingly uncomfortable. Finally, she interrupted me and said that she just couldn't let me go on. She had read the exact ideas that I claimed as my own in another book. I assured her that she was confused, and I continued.

She interrupted me again, this time angrily. She said she was not confused and named the book from which I was reading, having earlier received the information from me in our preclass set-up. At this point, I let myself appear more anxious about her words. Her concern grew, and she persisted in her comments until I finally admitted that I hadn't written the material. Acting ashamed, I revealed the book to the class. The kids' mouths opened, some in confused grins, some greatly concerned, not knowing what to believe.

The parent let me have it then. She reminded me that I was in a position of trust as a teacher—how dare I break that trust! She said that I was being a terrible role model and that my students would never again trust my writings or teaching. She declared that this was a breach of professional conduct and that my principal would be informed. Throughout all of this, I countered her points with the excuses that students often make when caught plagiarizing: It's only a small part. The rest of the writing is original; what does it matter that this one part was written by someone else? I've never done it before, and I'm not ever going to do it again, so it's not that bad.

The students' faces dissolved into disbelief, some into anger. Students vicariously experienced the uncomfortable feeling of being trapped in a lie and having one's reputation impugned. At the height of the emotional tension between the parent and me, I paused and asked the students, “Have you had enough?” With a smile and a thank-you to the parent assistant, I asked how many folks would like to learn five ways not to plagiarize material; then I went to the chalkboard.

Students breathed a sigh of relief. Notebooks flew onto desktops, and pens raced across paper to get down everything I taught for the rest of class; they hung on every word. Students wanted to do anything to avoid the “yucky” feelings associated with plagiarism that they had experienced moments ago. I taught them ways to cite sources, how to paraphrase another's words, and how many words from an original source we could use before we were lifting too much. We discussed the legal ramifications of plagiarism. Later, we applauded the acting talent of our parent assistant.

One student in the room that day reflected on this lesson at the end of the year:

I know I'll never forget when my teacher got “caught” plagiarizing. The sensations were simply too real.... Although my teacher is extremely moral, it was frightening how close to home it struck. The moment when my teacher admitted it, the room fell silent. It was awful. All my life, teachers have preached about plagiarism, and it never really sank in. But when you actually experience it, it's a whole different story.

To this day, students visit me from high school and college and say, “I was tempted to plagiarize this one little bit on one of my papers, but I didn't because I remembered how mad I was at you.” That's a teacher touchdown.

—Rick Wormeli

ReferencesGlynn, C. (2001). Learning on their feet. Shoreham, VT: Discover Writing Press.

Jackson, A., & Davis, G. (2000). Turning points 2000: Educating adolescents in the 21st century. New York: Carnegie Corporation.

National Middle School Association. (2003). This we believe: Successful schools for young adolescents. Westerville, OH: Author.

Pinar, W. F., Reynolds, W. M., Slattery, P., & Taubman, P. M. (2000). Understanding curriculum. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Wormeli, R. (1999). The test of accountability in middle school. Middle Ground, 3(7), 17–18, 53.

Wormeli, R. (2001). Meet me in the middle. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.

Wormeli, R. (2005). Summarization in any subject: 50 techniques to improve student learning. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Rick Wormeli (703-620-2447; [email protected]) taught young adolescents for 25 years. He is now a consultant who works with administrators and teachers across the United States. He resides in Herndon, Virginia.

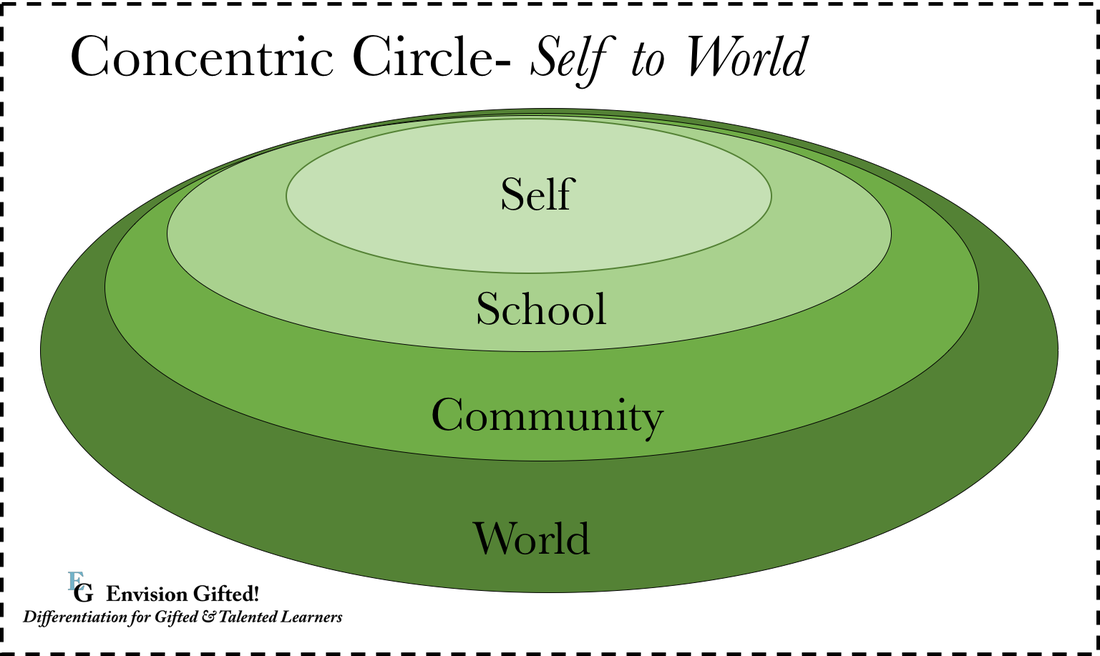

Concentric Circles

circles, arcs, or other shapes that share the same center, the larger often completely surrounding the smaller.

circles, arcs, or other shapes that share the same center, the larger often completely surrounding the smaller.