HOW TO SHARPEN PENCILS from Pricefilms on Vimeo.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uOk0vOup4yA

Click to set custom HTML

Click to set custom HTML

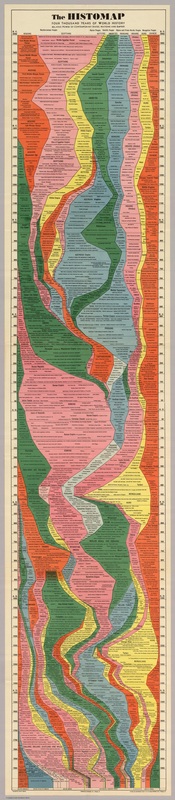

In the image above, we see a slice of an impressive pre-internet macro-infographic called a “Histomap.” Its creator John B. Sparks (who later created “histomaps” of religion and evolution) published the graphic in 1931 with Rand McNally. The five foot long chart—purportedly covering 4,000 years of “world” history—is, in fact, an example of an early illustration trend called the “outline,” of which Rebecca Onion at Slate writes: “large subjects (the history of the world! Every school of philosophy! All of modern physics!) were distilled into a form comprehensible to the most uneducated layman.” Here we have the full description of most every political chart, graph, or animation in U.S.A. Today, most Internet news sites, and, of course, The Onion.

The similarity here isn’t simply one of form. The “outline” functioned in much the same way that simplified animations do—condensing heavy, contentious theoretical freight trains and ideological baggage. Rebecca Onion describes the chart as an artifact very much of its time, presenting a version of history prominent in the U.S. between the wars. Onion writes:

The chart emphasizes domination, using color to show how the power of various “peoples” (a quasi-racial understanding of the nature of human groups, quite popular at the time) evolved throughout history.

Sparks’ map, however, remains an interesting document because of its seeming disinteredness. While the focus on racialism and imperial conquest may seem to place Sparks in company with populist “scientific” racists of the period like Lothrop Stoddard (whom Tom Buchanan quotes in Fitzgerald’s Gatsby), it would also seem that his design has much in common with early Enlightenment figures whose conception of time was not necessarily linear. Following classical models, thinkers like Thomas Hobbes tended to divide historical epochs into rising and falling actions of various people groups, rather than the gradual ascent of one race over all others towards an end of history. For example, poet Abraham Cowley writes a compressed “universal history” in his 1656 poem “To Mr. Hobbes,” moving from Aristotle (the “Stagirite”) to the poem’s subject Thomas Hobbes. The movement is progressive, yet the historical representatives of each civilization receive some equal weight and similar emphasis.

Long did the mighty Stagirite retain

The universal Intellectual reign,

Saw his own Countreys short-liv’ed Leopard slain;

The stronger Roman-Eagle did out-fly,

Oftner renewed his Age, and saw that Dy.

Mecha it self, in spight of Mahumet possest,

And chas’ed by a wild Deluge from the East,

His Monarchy new planted in the West.

But as in time each great imperial race

Degenerates, and gives some new one place:

The period of Cowley recognized theories of racial, cultural, and natural supremacy, but such qualities, as in Sparks’ map, were the product of a long line of succession from equally powerful and noteworthy empires and groups to others, not a social evolution in which a superior race naturally arose. Rand McNally advertised the chart as presenting “the march of civilization, from the mud huts of the ancients thru the monarchistic glamour of the middle ages to the living panorama of life in present day America.” While the blurb is filled with pseudoscientific colonialist talking points, the chart itself has the dated, yet strikingly egalitarian arrangement of information that—like much of the illustration in National Geographic—sought to accommodate the best consensus models of the times, displaying, but not proselytizing, its biases.

The similarity here isn’t simply one of form. The “outline” functioned in much the same way that simplified animations do—condensing heavy, contentious theoretical freight trains and ideological baggage. Rebecca Onion describes the chart as an artifact very much of its time, presenting a version of history prominent in the U.S. between the wars. Onion writes:

The chart emphasizes domination, using color to show how the power of various “peoples” (a quasi-racial understanding of the nature of human groups, quite popular at the time) evolved throughout history.

Sparks’ map, however, remains an interesting document because of its seeming disinteredness. While the focus on racialism and imperial conquest may seem to place Sparks in company with populist “scientific” racists of the period like Lothrop Stoddard (whom Tom Buchanan quotes in Fitzgerald’s Gatsby), it would also seem that his design has much in common with early Enlightenment figures whose conception of time was not necessarily linear. Following classical models, thinkers like Thomas Hobbes tended to divide historical epochs into rising and falling actions of various people groups, rather than the gradual ascent of one race over all others towards an end of history. For example, poet Abraham Cowley writes a compressed “universal history” in his 1656 poem “To Mr. Hobbes,” moving from Aristotle (the “Stagirite”) to the poem’s subject Thomas Hobbes. The movement is progressive, yet the historical representatives of each civilization receive some equal weight and similar emphasis.

Long did the mighty Stagirite retain

The universal Intellectual reign,

Saw his own Countreys short-liv’ed Leopard slain;

The stronger Roman-Eagle did out-fly,

Oftner renewed his Age, and saw that Dy.

Mecha it self, in spight of Mahumet possest,

And chas’ed by a wild Deluge from the East,

His Monarchy new planted in the West.

But as in time each great imperial race

Degenerates, and gives some new one place:

The period of Cowley recognized theories of racial, cultural, and natural supremacy, but such qualities, as in Sparks’ map, were the product of a long line of succession from equally powerful and noteworthy empires and groups to others, not a social evolution in which a superior race naturally arose. Rand McNally advertised the chart as presenting “the march of civilization, from the mud huts of the ancients thru the monarchistic glamour of the middle ages to the living panorama of life in present day America.” While the blurb is filled with pseudoscientific colonialist talking points, the chart itself has the dated, yet strikingly egalitarian arrangement of information that—like much of the illustration in National Geographic—sought to accommodate the best consensus models of the times, displaying, but not proselytizing, its biases.

The New America from Nando Costa on Vimeo.

Click to set custom HTML

Richard Feynman was a once in a generation intellectual. He had no shortage of brains. (In 1965, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on quantum electrodynamics.) He had charisma. (Witness this outtake from his 1964 Cornell physics lectures available here.) He knew how to make science and academic thought available, even entertaining, to a broader public. (We’ve highlighted two public TV programs hosted by Feynman here and here.) And he knew how to have fun. The clip above brings it all together. Hope you enjoy, and don’t miss our collection of Great Science Videos, or many free physics courses in our big collection of Free Online Courses.

The Road From Karakol from Outdoor Research on Vimeo.

JACK from Grace Jackson on Vimeo.