Charlie Chaplin

This film marks the first appearance of Charlie Chaplin's "The Little Tramp" character.

Possibly the most important 6 min. film in the world. Charlie's 2nd Film in Hollywood. Charlie the Tramp comes to a kid auto race, which a director just happens to be filming.

Charlie constantly gets in the way, annoying the director, cameraman, and public.

Possibly the most important 6 min. film in the world. Charlie's 2nd Film in Hollywood. Charlie the Tramp comes to a kid auto race, which a director just happens to be filming.

Charlie constantly gets in the way, annoying the director, cameraman, and public.

Charlie Chaplin

Mack Sennet Studios 1916 to today

macksennettstudios.net/

HISTORY OF THE Mack Sennet STUDIOS

When the studio opened in 1916, Los Angeles was establishing a relationship with the nascent film industry that continues to define its identity to this day. There was room for the likes of entrepreneur Mack Sennett and comedienne Mabel Normand to carve out a creative space in an industry that became the nexus for art, commerce and craft. The neighborhood of Edendale, as the Silver Lake/ Echo Park area was known at the time, was the site of many of the original studios. While women gained the right to vote in 1919, Normand was running the studio and working as one of Hollywood’s first female directors. She directed unknown British vaudeville comic Charlie Chaplin in his first short films and shares credit for inventing the pie in the face gag that would become a Sennett comedy staple. In Normand’s time, eighty percent of films seen around the world were made in Los Angeles; in 2013 only two studio films were shot in LA. Mack Sennett Studios like the city itself has evolved in response to a changing industry characterized by reinvention. The once open-air filming platforms topped by canvas tarps were eventually enclosed as cinema technology allowed for sound recording and artificial lighting. Over the course of a century, the site has operated as a shop that produced hand-painted backdrops, later housed a studio lighting and equipment company and its stages have been used for countless music video, film and photography shoots. — forward written by Nicola Goode

macksennettstudios.net/

HISTORY OF THE Mack Sennet STUDIOS

When the studio opened in 1916, Los Angeles was establishing a relationship with the nascent film industry that continues to define its identity to this day. There was room for the likes of entrepreneur Mack Sennett and comedienne Mabel Normand to carve out a creative space in an industry that became the nexus for art, commerce and craft. The neighborhood of Edendale, as the Silver Lake/ Echo Park area was known at the time, was the site of many of the original studios. While women gained the right to vote in 1919, Normand was running the studio and working as one of Hollywood’s first female directors. She directed unknown British vaudeville comic Charlie Chaplin in his first short films and shares credit for inventing the pie in the face gag that would become a Sennett comedy staple. In Normand’s time, eighty percent of films seen around the world were made in Los Angeles; in 2013 only two studio films were shot in LA. Mack Sennett Studios like the city itself has evolved in response to a changing industry characterized by reinvention. The once open-air filming platforms topped by canvas tarps were eventually enclosed as cinema technology allowed for sound recording and artificial lighting. Over the course of a century, the site has operated as a shop that produced hand-painted backdrops, later housed a studio lighting and equipment company and its stages have been used for countless music video, film and photography shoots. — forward written by Nicola Goode

Click to set custom HTML

THE CHILDREN OF CHARLIE CHAPLIN

Doing research on comedians, I discovered that a lot of them adopted their children like Jack Benny, George Burns, and Bob Hope. However, I was always amazed at how many children Charlie Chaplin had. He had 11 children between 1919 and 1962. It was an amazing record, and knowing how much of a genius Chaplin was at everything else, it only goes to show he was a genius at having children as well. Here is a run down of his children:

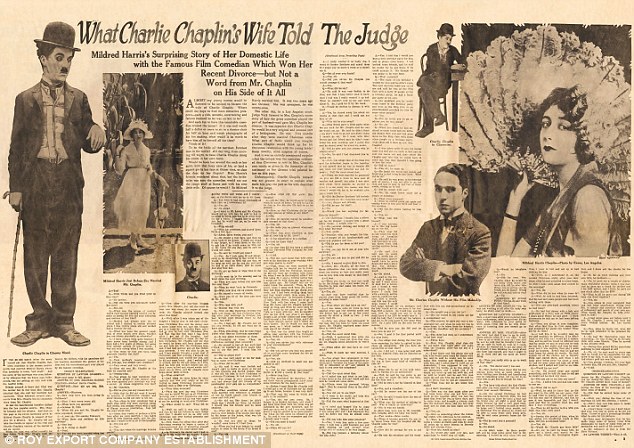

Norman Spencer Chaplin was born July 7th, 1919. Sadly the baby died three days later. The mother was his first wife Mildred Harris. Harris and Chaplin divorced in 1921.

Charles Spencer Chaplin, Jr. was born May 5, 1925. Charlie's Jr. was in Limelight (1952) as one of the clowns with his father. As young children, he and his brother were used as pawns in their mother's bitter divorce from Charlie Chaplin, during which a lot of the couple's "dirty linen" was aired in sensational—and very public—divorce hearings. Following the divorce, the young brothers were raised by their mother and maternal grandmother until the mid-1930s, when they began to make frequent visits to their father. He is burried next to his maternal grandmother Lillian Grey (1889-1985).

Sydney Earle Chaplin was born March 30th, 1926. Sydney played with his father in Limelight in the role as Neville. In 1957 he won Tony Award for Best Performance by a Featured Actor in a Musical for Bells Are Ringing, opposite Judy Holliday, and received a Tony nomination for his performance as Nicky Arnstein, the gambling first husband of Fanny Brice, opposite Barbra Streisand, in the Broadway musical Funny Girl in 1964.Until he died, he still attended Chaplin events held for his father and can be seen in many film interviews about Charlie. Sydney died March 3, 2009.

Geraldine Leigh Chaplin was born August 1, 1944. Geraldine was an actress known for many roles, but first recognized for her work in Dr. Zhivago. She also played her own grandmother in the 1992 Richard Attenborough film of Chaplin. Her first film appearance was in Limelight with brother Michael and sister Josephine at the beginning of the film.

Michael John Chaplin was born March 7, 1946 He appeared in Limelight with his sisters in the beginning and played the boy 'Rupert Macabee' in King of New York.

Josephine Hannah Chaplin was born March 28, 1949. She has been in a number of films, including her father's Limelight and A Countess from Hong Kong, and Pasolini´s Canterbury Tales. She had a son Julien Ronet (born 1980) by Maurice Ronet, with whom she lived until his death.

Victoria Chaplin was born May 19, 1951. Chaplin was born in the United States but grew up in Switzerland. As a teenager, she appeared as an extra in her father's last film, A Countess from Hong Kong (1967). Her father also wanted her to star in the main role of a winged girl found from the Amazonian rainforest in his next planned film, The Freak, in 1969. However, the project was never filmed because of his declining health and because Chaplin eloped with the French actor Jean-Baptiste Thiérrée.

Eugene Anthony Chaplin was born August 23, 1953. He is a Swiss recording engineer and documentary filmmaker. He is the president of the International Comedy Film Festival of Vevey, Switzerland. He directed the documentary film Charlie Chaplin: A Family Tribute produced by Jarl Ale de Basseville and created the musical "Smile", which is a narration of Charlie Chaplin's life through his music. As a recording engineer, he worked with The Rolling Stones, David Bowie, and Queen.

Jane Cecil Chaplin was born May 23, 1957 and married film producer Ilya Salkind. She has two children.

Annette Emily Chaplin was born December 3, 1959 and is the most private of all of the Chaplin children.

Christopher James Chaplin was born July 6 1962 in Corsier-sur-Vevey, Switzerland. Christopher is a composer and actor. He is the youngest son of film comedian Charlie Chaplin and his fourth wife, Oona O'Neill.

What also is so remarkable is that the Chaplin children did not seem to fall into the pitfalls that the children of other legends have. They all are talented and seemingly well adjusted children. His children may be Charlie Chaplin's most remarkable body of work...

Doing research on comedians, I discovered that a lot of them adopted their children like Jack Benny, George Burns, and Bob Hope. However, I was always amazed at how many children Charlie Chaplin had. He had 11 children between 1919 and 1962. It was an amazing record, and knowing how much of a genius Chaplin was at everything else, it only goes to show he was a genius at having children as well. Here is a run down of his children:

Norman Spencer Chaplin was born July 7th, 1919. Sadly the baby died three days later. The mother was his first wife Mildred Harris. Harris and Chaplin divorced in 1921.

Charles Spencer Chaplin, Jr. was born May 5, 1925. Charlie's Jr. was in Limelight (1952) as one of the clowns with his father. As young children, he and his brother were used as pawns in their mother's bitter divorce from Charlie Chaplin, during which a lot of the couple's "dirty linen" was aired in sensational—and very public—divorce hearings. Following the divorce, the young brothers were raised by their mother and maternal grandmother until the mid-1930s, when they began to make frequent visits to their father. He is burried next to his maternal grandmother Lillian Grey (1889-1985).

Sydney Earle Chaplin was born March 30th, 1926. Sydney played with his father in Limelight in the role as Neville. In 1957 he won Tony Award for Best Performance by a Featured Actor in a Musical for Bells Are Ringing, opposite Judy Holliday, and received a Tony nomination for his performance as Nicky Arnstein, the gambling first husband of Fanny Brice, opposite Barbra Streisand, in the Broadway musical Funny Girl in 1964.Until he died, he still attended Chaplin events held for his father and can be seen in many film interviews about Charlie. Sydney died March 3, 2009.

Geraldine Leigh Chaplin was born August 1, 1944. Geraldine was an actress known for many roles, but first recognized for her work in Dr. Zhivago. She also played her own grandmother in the 1992 Richard Attenborough film of Chaplin. Her first film appearance was in Limelight with brother Michael and sister Josephine at the beginning of the film.

Michael John Chaplin was born March 7, 1946 He appeared in Limelight with his sisters in the beginning and played the boy 'Rupert Macabee' in King of New York.

Josephine Hannah Chaplin was born March 28, 1949. She has been in a number of films, including her father's Limelight and A Countess from Hong Kong, and Pasolini´s Canterbury Tales. She had a son Julien Ronet (born 1980) by Maurice Ronet, with whom she lived until his death.

Victoria Chaplin was born May 19, 1951. Chaplin was born in the United States but grew up in Switzerland. As a teenager, she appeared as an extra in her father's last film, A Countess from Hong Kong (1967). Her father also wanted her to star in the main role of a winged girl found from the Amazonian rainforest in his next planned film, The Freak, in 1969. However, the project was never filmed because of his declining health and because Chaplin eloped with the French actor Jean-Baptiste Thiérrée.

Eugene Anthony Chaplin was born August 23, 1953. He is a Swiss recording engineer and documentary filmmaker. He is the president of the International Comedy Film Festival of Vevey, Switzerland. He directed the documentary film Charlie Chaplin: A Family Tribute produced by Jarl Ale de Basseville and created the musical "Smile", which is a narration of Charlie Chaplin's life through his music. As a recording engineer, he worked with The Rolling Stones, David Bowie, and Queen.

Jane Cecil Chaplin was born May 23, 1957 and married film producer Ilya Salkind. She has two children.

Annette Emily Chaplin was born December 3, 1959 and is the most private of all of the Chaplin children.

Christopher James Chaplin was born July 6 1962 in Corsier-sur-Vevey, Switzerland. Christopher is a composer and actor. He is the youngest son of film comedian Charlie Chaplin and his fourth wife, Oona O'Neill.

What also is so remarkable is that the Chaplin children did not seem to fall into the pitfalls that the children of other legends have. They all are talented and seemingly well adjusted children. His children may be Charlie Chaplin's most remarkable body of work...

Chaplin familyFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaThe Chaplin family is a multinational acting family. They are the descendants of Hannah Harriet Pedlingham Hill, mother of Sydney John Chaplin (born Sydney John Hill), Charles Spencer "Charlie" Chaplin, Jr., and George Wheeler Dryden.

Family members[edit]The members of the Chaplin family include:

(ii) Lita Grey (1908–1995), 2 sons.

(iii) Paulette Goddard (1910–1990), no children.

(iv) Oona O'Neill (1925–1991), daughter of American playwright Eugene O'Neill and Agnes Boulton; 3 sons, 5 daughters.

(ii) Patricia Betaudier

Family members[edit]The members of the Chaplin family include:

- Charles Spencer Chaplin, Sr. (1863–1901)

- Hannah Harriet Pedlingham Hill (1865–1928); 3 sons

- Sydney John Chaplin (1885–1965), born Sydney John Hill; alleged son of Sydney Hawkes; 2 marriages, no children.

- Charles Spencer "Charlie" Chaplin, Jr. (1889–1977), son of Charles Spencer Chaplin, Sr. (1863-1901); 4 marriages, 6 sons, 5 daughters.

- Norman Spencer Chaplin (1919–1919), died 3 days after birth.

(ii) Lita Grey (1908–1995), 2 sons.

- Charles Spencer Chaplin III (1925–1968).

- Susan Maree Chaplin, by Susan Magness

- 4 children[1] by Scott Newton

- Sydney Earl Chaplin (1926–2009).[2]

- Stephan Chaplin, by French dancer and actor Noelle Adam

- Tamara Chaplin[3]

(iii) Paulette Goddard (1910–1990), no children.

(iv) Oona O'Neill (1925–1991), daughter of American playwright Eugene O'Neill and Agnes Boulton; 3 sons, 5 daughters.

- Geraldine Chaplin (born 1944).

- Shane Saura (born 1974), by Carlos Saura.[3]

- Oona Castilla (born 1986), by Patricio Castilla.

- Michael Chaplin (born 1946)

(ii) Patricia Betaudier

- Kathleen Chaplin (born 1975)[3]

- Dolores Chaplin (born 1979)[3]

- Carmen Chaplin (born 1972)

- Tracy Chaplin[3]

- Josephine Chaplin (born 1949).

- Charly Sistovaris (born 1971), by Nicholas Sistovaris[5]

- 1 daughter (born 2011)[5]

- Julien Ronet (born 1980), by French actor Maurice Ronet.

- Arthur Gardin, by archeologist Jean-Claude Gardin.[3]

- Victoria Chaplin (born 1951), married Jean-Baptiste Thierrée.

- Aurélia Thierrée (born 1971)[6]

- James Thierrée (born 1974)

- Eugene Anthony Chaplin (born 1953), married Bernadette McCready.

- Kiera Chaplin (born 1982)

- Laura Chaplin (born 1987)[7][8]

- Kevin Chaplin[3]

- Spencer Chaplin[3]

- Shannon Chaplin[3]

- Jane Cecil Chaplin (born 1957), married film producer Ilya Salkind.[9]

- Annette Emily Chaplin (born 1959)

- Christopher Chaplin (born 1962)

Douglas Fairbanks

After marrying for the third time, Fairbanks retired from acting. He died of a heart attack on December 12, 1939, at the age of 56, at his home in Santa Monica, California.

After marrying for the third time, Fairbanks retired from acting. He died of a heart attack on December 12, 1939, at the age of 56, at his home in Santa Monica, California.

The Charlie Chaplin Studio was built by the famous comedian after he signed with First National in 1917, his first independent production deal.

"At the end of the Mutual contract," Chaplin later wrote, "I was anxious to get started with First National, but we had no studio. I decided to buy land in Hollywood and build one. The site was the corner of Sunset and La Brea and had a very fine ten-room house and five acres of lemon, orange and peach trees. We built a perfect unit, complete with developing plant, cutting room, and offices."

The land was located just south of the mansion owned by Charles Chaplin's brother Sydney, the business head of the Chaplin film company.

Chaplin built the English cottage-style studio in three months beginning in November 1917, at a reported cost of only $35,000. The property was located just south of the mansion owned by his brother Sydney Chaplin, the business head of the Chaplin film company (Sydney's house has since been torn down to make way for an electronics store). Every independent film he ever produced was made at the studio including the classics The Kid (1921), The Gold Rush (1925), City Lights (1931) and The Great Dictator (1940). His last film shot there was Limelight (1952). Charlie Chaplin's concrete footprints can still be found in front of Sound Stage #3.

The Charlie Chaplin Studio on LaBrea Avenue in Hollywood. Notice the orchard grove next to the property.

He sold the studio in 1953, to a New York real estate firm William Zeckendorf's Webb & Knapp for $650,000. The plan was to tear down the studio, but instead it was leased out to a Chicago television production company. The lot became known as the Kling Studios, and such shows as the George Reeves The Adventures of Superman series, The Red Skelton Show, and the original Perry Mason (CBS) were produced there.

The lot was briefly owned by Red Skelton from 1958 to 1962, then by CBS until 1966 when it became the home of A&M Records and Tijuana Brass Enterprises, Inc. In 1969 , the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Board named the studios a historic cultural monument. The recording studio has been used by many major artists such as Bruce Springsteen and the Rolling Stones. It was also the site of the memorable "We Are the World" recording of which brought together a who's-who of music talent onto the Charlie Chaplin sound stage in 1985.

The Henson family purchases the famous Charlie Chaplin Studio in 2000.

In 1992, A&M Records was acquired by Polygram, Inc., and during the consolidation of the recording industry in the late 1990s, the owners looked the sell the property. In February 2000, the Henson family announced that they bought the property for $12.5 million to become the headquarters of their independent production operation the Jim Henson Company. It subsequently became known as the Henson Recording Studios.

"At the end of the Mutual contract," Chaplin later wrote, "I was anxious to get started with First National, but we had no studio. I decided to buy land in Hollywood and build one. The site was the corner of Sunset and La Brea and had a very fine ten-room house and five acres of lemon, orange and peach trees. We built a perfect unit, complete with developing plant, cutting room, and offices."

The land was located just south of the mansion owned by Charles Chaplin's brother Sydney, the business head of the Chaplin film company.

Chaplin built the English cottage-style studio in three months beginning in November 1917, at a reported cost of only $35,000. The property was located just south of the mansion owned by his brother Sydney Chaplin, the business head of the Chaplin film company (Sydney's house has since been torn down to make way for an electronics store). Every independent film he ever produced was made at the studio including the classics The Kid (1921), The Gold Rush (1925), City Lights (1931) and The Great Dictator (1940). His last film shot there was Limelight (1952). Charlie Chaplin's concrete footprints can still be found in front of Sound Stage #3.

The Charlie Chaplin Studio on LaBrea Avenue in Hollywood. Notice the orchard grove next to the property.

He sold the studio in 1953, to a New York real estate firm William Zeckendorf's Webb & Knapp for $650,000. The plan was to tear down the studio, but instead it was leased out to a Chicago television production company. The lot became known as the Kling Studios, and such shows as the George Reeves The Adventures of Superman series, The Red Skelton Show, and the original Perry Mason (CBS) were produced there.

The lot was briefly owned by Red Skelton from 1958 to 1962, then by CBS until 1966 when it became the home of A&M Records and Tijuana Brass Enterprises, Inc. In 1969 , the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Board named the studios a historic cultural monument. The recording studio has been used by many major artists such as Bruce Springsteen and the Rolling Stones. It was also the site of the memorable "We Are the World" recording of which brought together a who's-who of music talent onto the Charlie Chaplin sound stage in 1985.

The Henson family purchases the famous Charlie Chaplin Studio in 2000.

In 1992, A&M Records was acquired by Polygram, Inc., and during the consolidation of the recording industry in the late 1990s, the owners looked the sell the property. In February 2000, the Henson family announced that they bought the property for $12.5 million to become the headquarters of their independent production operation the Jim Henson Company. It subsequently became known as the Henson Recording Studios.

The Charlie Chaplin Centennial: A Genius Is RevisitedBy VINCENT CANBY

Published: April 14, 1989In the world of silent-film comedians, everything that goes up - be it a brick, a bottle, a pail or a pie - must come down on a foot or a head. Banana peels are discarded to be slipped upon, streets are freshly tarred to be stuck in. God designed rear ends to be kicked (squarely) or to be placed (firmly) atop objects either sharp (tacks are favored) or hot (preferably on fire).

The genius of the films of Charlie Chaplin is that he invested this utterly predictable world with such genuine astonishment, delight and humanity and, in passing, discovered, almost in spite of himself, the particular existing within the generic.

One of the many rewards of the Museum of Modern Art's centennial retrospective, opening today, is following the sometimes lurching, sometimes soaring progress of the life begun April 16, 1889, as Charles Spencer Chaplin. That became simply ''Charlie'' at the height of his popularity and, in 1975, two years before his death, Sir Charles.

The only problem with Charlie's 100th birthday is that it doesn't come around more often, in this way to direct popular attention to a body of work that seems to be sliding upward to pedagogic heaven, worshiped in print but largely unseen by people who just want to laugh. At the Video Vault, on Broadway near 88th Street, requests for Chaplin are far outnumbered by requests for the Marx Brothers.

The great Marxes, including the honking Harpo, talk and talk and talk, often with sublime irrelevance. This gives them a decided edge over the wizard who came out of pre-World War I English music hall to become a master of cinema pantomime, and who successfully resisted sound until 1931 (''City Lights''). Yesterday's idol of the masses is today's museum piece. The museum is the richer for it.

Charlie makes demands on contemporary moviegoers. Although he had equipped all of his best silent films with soundtracks before he died, his movies were designed to be seen through eyes not turned lazy by din. Their joys remain transporting and, as a sort of bonus, instructive for their technique.

In a brilliant sequence from his 1918 short ''A Dog's Life,'' Charlie's camera sits unmoving, much like a famished dog anticipating dinner, as it watches every gesture of the Tramp in the middle distance at an outdoor cake stand. Every time the stand's owner turns his back, the Tramp snatches, chews and swallows a cake. The camera does not cut away. The tension mounts as a dozen cakes are consumed in quick succession. It has to end badly for the Tramp, but then Charlie surprises again.

Chaplin certainly didn't intend to instruct audiences on the benefits of full-figure framing in which two, three or even four actors are seen in the same shot. That came naturally to a performer in music hall, and it was faster and cheaper to shoot in one take.

It also shows today's audiences how much we are missing in visual comedy when it's broken up into close-ups and cuts between images. This busyness doesn't simply telegraph comedy routines. It presents them piecemeal, the parts labeled so that there's very little for the viewer to do except offer admiration.

Chaplin was not wedded to a single technique. He used whatever was necessary to get the point across. There are fine one-take routines in ''The Idle Class'' (1921), possibly his most thoroughly, consistently funny short, as well as cross-cutting, close-ups and all of the other things that have evolved over the years into the jargon of the trade.

One of the biggest impediments to Charlie's popularity today is the heart the Tramp wears on his sleeve. Sometimes, as in ''The Circus'' and ''The Kid,'' it is larger and more squashy than at other times (''The Idle Class''). Yet ''The Kid'' (1921) and ''The Circus'' (1928) somehow manage to make acceptable even those feelings that are either overstated or slightly bogus. In ''The Kid,'' his method is the amazing performance by Jackie Coogan in the title role and, in ''The Circus,'' a series of routines as superbly conceived, choreographed and pared down as any in all of Chaplin's work.

When one watches the Chaplin films in some sort of chronological order, one can see the sentimentality to be a convention that he both endorsed and was rebelling against. The anger that would later be expressed rather more sharply in ''Monsieur Verdoux'' (1947) and ''A King in New York'' (1957) is already apparent in the closing image of ''The Idle Class'': a furious kick in the pants to a representative of the ruling elite.

''The Pilgrim'' (1923), about an escaped convict who masquerades as a Protestant minister, prompted a formal protest from the South Carolina Ku Klux Klan. The Evangelical Ministers' Association in Atlanta called it ''an insult to the Gospel.''

As the Chaplin work accumulates, one can also see the way in which the standard figures of silent-film comedy began to take on a particular identity. It wasn't because the people who made silent films were incredibly naive that they used stereotypes for ''the landlord,'' ''the widow,'' ''the pickpocket,'' ''the policeman.'' They were functions of the comedy, much like such New Yorker cartoon figures as Charles Addams's portly old-man-about-Manhattan and George Price's knobby-toed housewife.

In Chaplin's finest work, the stereotypes take on particular identity, both through the brilliance of Chaplin's casting and in the things he gives the characters to do. ''The Pilgrim'' possesses what must be the most hilariously awful child in the history of the cinema, at least until the advent of W. C. Fields. May Wells, who plays the brat's mother, begins as a stock character and ends as idiosyncratic as the subject of a Daumier sketch.

There is not a single Chaplin feature that should be missed in the museum retrospective, though ''A Countess From Hong Kong'' (1967) can be put near the bottom of the list. Near the top should be ''A Woman of Paris'' (1923), the ''serious'' film Chaplin so admired himself and which was his only film, aside from ''A Countess'' in which he did not star. Though ''serious,'' ''A Woman of Paris'' is also very funny and, in its manners, uncharacteristically sophisticated for its time.

Everything in Chaplin's work comes together in his chef d'oeuvre, ''City Lights,'' in which social satire, human comedy, slapstick, sentiment and even Charlie's own view of himself (as the artist lonely in his great talent) blend without lumps. It's also possible to see how the silent-film genius was itching to talk. One of the film's funniest moments is an exchange of dialogue on title cards. (''City Lights'' uses only music and sound effects.) The Tramp and his millionaire pal, both crazy-drunk after a night on the town, are driving home in the millionaire's sporty roadster. The car weaves and bumps along, over curbs, along sidewalks and down the wrong side of the street. ''Be careful of your driving,'' says the Tramp. Says his cheerfully anesthetized on-again, off-again best-friend, ''Am I driving?''

He was, said Federico Fellini at the time Chaplin died, ''a sort of Adam from whom we are all descended.''

Published: April 14, 1989In the world of silent-film comedians, everything that goes up - be it a brick, a bottle, a pail or a pie - must come down on a foot or a head. Banana peels are discarded to be slipped upon, streets are freshly tarred to be stuck in. God designed rear ends to be kicked (squarely) or to be placed (firmly) atop objects either sharp (tacks are favored) or hot (preferably on fire).

The genius of the films of Charlie Chaplin is that he invested this utterly predictable world with such genuine astonishment, delight and humanity and, in passing, discovered, almost in spite of himself, the particular existing within the generic.

One of the many rewards of the Museum of Modern Art's centennial retrospective, opening today, is following the sometimes lurching, sometimes soaring progress of the life begun April 16, 1889, as Charles Spencer Chaplin. That became simply ''Charlie'' at the height of his popularity and, in 1975, two years before his death, Sir Charles.

The only problem with Charlie's 100th birthday is that it doesn't come around more often, in this way to direct popular attention to a body of work that seems to be sliding upward to pedagogic heaven, worshiped in print but largely unseen by people who just want to laugh. At the Video Vault, on Broadway near 88th Street, requests for Chaplin are far outnumbered by requests for the Marx Brothers.

The great Marxes, including the honking Harpo, talk and talk and talk, often with sublime irrelevance. This gives them a decided edge over the wizard who came out of pre-World War I English music hall to become a master of cinema pantomime, and who successfully resisted sound until 1931 (''City Lights''). Yesterday's idol of the masses is today's museum piece. The museum is the richer for it.

Charlie makes demands on contemporary moviegoers. Although he had equipped all of his best silent films with soundtracks before he died, his movies were designed to be seen through eyes not turned lazy by din. Their joys remain transporting and, as a sort of bonus, instructive for their technique.

In a brilliant sequence from his 1918 short ''A Dog's Life,'' Charlie's camera sits unmoving, much like a famished dog anticipating dinner, as it watches every gesture of the Tramp in the middle distance at an outdoor cake stand. Every time the stand's owner turns his back, the Tramp snatches, chews and swallows a cake. The camera does not cut away. The tension mounts as a dozen cakes are consumed in quick succession. It has to end badly for the Tramp, but then Charlie surprises again.

Chaplin certainly didn't intend to instruct audiences on the benefits of full-figure framing in which two, three or even four actors are seen in the same shot. That came naturally to a performer in music hall, and it was faster and cheaper to shoot in one take.

It also shows today's audiences how much we are missing in visual comedy when it's broken up into close-ups and cuts between images. This busyness doesn't simply telegraph comedy routines. It presents them piecemeal, the parts labeled so that there's very little for the viewer to do except offer admiration.

Chaplin was not wedded to a single technique. He used whatever was necessary to get the point across. There are fine one-take routines in ''The Idle Class'' (1921), possibly his most thoroughly, consistently funny short, as well as cross-cutting, close-ups and all of the other things that have evolved over the years into the jargon of the trade.

One of the biggest impediments to Charlie's popularity today is the heart the Tramp wears on his sleeve. Sometimes, as in ''The Circus'' and ''The Kid,'' it is larger and more squashy than at other times (''The Idle Class''). Yet ''The Kid'' (1921) and ''The Circus'' (1928) somehow manage to make acceptable even those feelings that are either overstated or slightly bogus. In ''The Kid,'' his method is the amazing performance by Jackie Coogan in the title role and, in ''The Circus,'' a series of routines as superbly conceived, choreographed and pared down as any in all of Chaplin's work.

When one watches the Chaplin films in some sort of chronological order, one can see the sentimentality to be a convention that he both endorsed and was rebelling against. The anger that would later be expressed rather more sharply in ''Monsieur Verdoux'' (1947) and ''A King in New York'' (1957) is already apparent in the closing image of ''The Idle Class'': a furious kick in the pants to a representative of the ruling elite.

''The Pilgrim'' (1923), about an escaped convict who masquerades as a Protestant minister, prompted a formal protest from the South Carolina Ku Klux Klan. The Evangelical Ministers' Association in Atlanta called it ''an insult to the Gospel.''

As the Chaplin work accumulates, one can also see the way in which the standard figures of silent-film comedy began to take on a particular identity. It wasn't because the people who made silent films were incredibly naive that they used stereotypes for ''the landlord,'' ''the widow,'' ''the pickpocket,'' ''the policeman.'' They were functions of the comedy, much like such New Yorker cartoon figures as Charles Addams's portly old-man-about-Manhattan and George Price's knobby-toed housewife.

In Chaplin's finest work, the stereotypes take on particular identity, both through the brilliance of Chaplin's casting and in the things he gives the characters to do. ''The Pilgrim'' possesses what must be the most hilariously awful child in the history of the cinema, at least until the advent of W. C. Fields. May Wells, who plays the brat's mother, begins as a stock character and ends as idiosyncratic as the subject of a Daumier sketch.

There is not a single Chaplin feature that should be missed in the museum retrospective, though ''A Countess From Hong Kong'' (1967) can be put near the bottom of the list. Near the top should be ''A Woman of Paris'' (1923), the ''serious'' film Chaplin so admired himself and which was his only film, aside from ''A Countess'' in which he did not star. Though ''serious,'' ''A Woman of Paris'' is also very funny and, in its manners, uncharacteristically sophisticated for its time.

Everything in Chaplin's work comes together in his chef d'oeuvre, ''City Lights,'' in which social satire, human comedy, slapstick, sentiment and even Charlie's own view of himself (as the artist lonely in his great talent) blend without lumps. It's also possible to see how the silent-film genius was itching to talk. One of the film's funniest moments is an exchange of dialogue on title cards. (''City Lights'' uses only music and sound effects.) The Tramp and his millionaire pal, both crazy-drunk after a night on the town, are driving home in the millionaire's sporty roadster. The car weaves and bumps along, over curbs, along sidewalks and down the wrong side of the street. ''Be careful of your driving,'' says the Tramp. Says his cheerfully anesthetized on-again, off-again best-friend, ''Am I driving?''

He was, said Federico Fellini at the time Chaplin died, ''a sort of Adam from whom we are all descended.''

UA was incorporated as a joint venture on February 5, 1919, by Pickford, Chaplin, Fairbanks, and Griffith. Each held a 20% stake, with the remaining 20% held by lawyer William Gibbs McAdoo.[3]The idea for the venture originated with Fairbanks, Chaplin, Pickford and cowboy star William S. Hart a year earlier. Already Hollywood veterans, the four stars talked of forming their own company to better control their own work.

They were spurred on by established Hollywood producers and distributors who were tightening their control over actor salaries and creative decisions, a process that evolved into the studio system. With the addition of Griffith, planning began, but Hart bowed out before anything was formalized. When he heard about their scheme, Richard A. Rowland, head of Metro Pictures, is said to have observed, "The inmates are taking over the asylum." The four partners, with advice from McAdoo (son-in-law and former Treasury Secretary of then-President Woodrow Wilson), formed their distribution company, with Hiram Abrams as its first managing director. Its headquarters was established at 729 Seventh Avenue in New York City.[4]

List of UA stockholders in 1920.The original terms called for each of the stars to produce five pictures each year. By the time the company was operational in 1920–1921, feature films were becoming more expensive and polished, and running times had settled at around ninety minutes (eight reels) and the original goal was abandoned.

D.W. Griffith, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin (seated) and Douglas Fairbanks at the signing of the contract establishing United Artists motion picture studio in 1919. Lawyers Albert Banzhaf (left) and Dennis F. O'Brien (right) stand in the background.UA's first film (His Majesty, the American by and starring Fairbanks) was a success. Funding for movies was limited. Without selling stock to the public, following the other studios, all United had for finance was weekly prepayment installments from theater owners for upcoming movies. As a result, production was slow and the company distributed an annual average of five films during its first five years.[5]

By 1924 Griffith had dropped out and the company was facing a crisis: the alternatives were to either bring in others to help support a costly distribution system or concede defeat.[citation needed] Veteran producer Joseph Schenck was hired as president.[5] He had been producing pictures for a decade,[citation needed] and he brought commitments for films starring his wife, Norma Talmadge,[5] his sister-in-law, Constance Talmadge,[citation needed] and his brother-in-law, Buster Keaton.[5] Contracts were signed with independent producers, most notably Samuel Goldwyn,[citation needed] and Howard Hughes.[5] In 1933, Schenck organized a new company with Darryl F. Zanuck, called Twentieth Century Pictures, which soon provided four pictures a year, forming half of UA's schedule.[5]

Schenck formed a separate partnership with Pickford and Chaplin to buy and build theaters under the United Artists name. They began international operations, first in Canada and then in Mexico. By the end of the 1930s, United Artists was represented in over 40 countries.

When he was denied an ownership share in 1935, Schenck resigned. He set up 20th Century Pictures' merger with Fox Film Corporation to form 20th Century Fox. Al Lichtman succeeded Schenck as company president. Other independent producers distributed through United Artists in the 1930s including: Walt Disney Productions, Alexander Korda, Hal Roach, David O. Selznick and Walter Wanger.[5] As the years passed, and the dynamics of the business changed, these "producing partners" drifted away. Samuel Goldwyn Productions and Disney went to RKO, and Wanger to Universal Pictures.

In the late 1930s, UA turned a profit. Goldwyn was providing most of the output for distribution. Goldwyn sued United several times for disputed compensation leading Goldwyn to leave. MGM's 1939 hit Gone with the Wind was supposed to be a UA release except that Selznick wanted Clark Gable, who was under contract to MGM, to play Rhett Butler. Also that year Fairbanks died.[5]

They were spurred on by established Hollywood producers and distributors who were tightening their control over actor salaries and creative decisions, a process that evolved into the studio system. With the addition of Griffith, planning began, but Hart bowed out before anything was formalized. When he heard about their scheme, Richard A. Rowland, head of Metro Pictures, is said to have observed, "The inmates are taking over the asylum." The four partners, with advice from McAdoo (son-in-law and former Treasury Secretary of then-President Woodrow Wilson), formed their distribution company, with Hiram Abrams as its first managing director. Its headquarters was established at 729 Seventh Avenue in New York City.[4]

List of UA stockholders in 1920.The original terms called for each of the stars to produce five pictures each year. By the time the company was operational in 1920–1921, feature films were becoming more expensive and polished, and running times had settled at around ninety minutes (eight reels) and the original goal was abandoned.

D.W. Griffith, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin (seated) and Douglas Fairbanks at the signing of the contract establishing United Artists motion picture studio in 1919. Lawyers Albert Banzhaf (left) and Dennis F. O'Brien (right) stand in the background.UA's first film (His Majesty, the American by and starring Fairbanks) was a success. Funding for movies was limited. Without selling stock to the public, following the other studios, all United had for finance was weekly prepayment installments from theater owners for upcoming movies. As a result, production was slow and the company distributed an annual average of five films during its first five years.[5]

By 1924 Griffith had dropped out and the company was facing a crisis: the alternatives were to either bring in others to help support a costly distribution system or concede defeat.[citation needed] Veteran producer Joseph Schenck was hired as president.[5] He had been producing pictures for a decade,[citation needed] and he brought commitments for films starring his wife, Norma Talmadge,[5] his sister-in-law, Constance Talmadge,[citation needed] and his brother-in-law, Buster Keaton.[5] Contracts were signed with independent producers, most notably Samuel Goldwyn,[citation needed] and Howard Hughes.[5] In 1933, Schenck organized a new company with Darryl F. Zanuck, called Twentieth Century Pictures, which soon provided four pictures a year, forming half of UA's schedule.[5]

Schenck formed a separate partnership with Pickford and Chaplin to buy and build theaters under the United Artists name. They began international operations, first in Canada and then in Mexico. By the end of the 1930s, United Artists was represented in over 40 countries.

When he was denied an ownership share in 1935, Schenck resigned. He set up 20th Century Pictures' merger with Fox Film Corporation to form 20th Century Fox. Al Lichtman succeeded Schenck as company president. Other independent producers distributed through United Artists in the 1930s including: Walt Disney Productions, Alexander Korda, Hal Roach, David O. Selznick and Walter Wanger.[5] As the years passed, and the dynamics of the business changed, these "producing partners" drifted away. Samuel Goldwyn Productions and Disney went to RKO, and Wanger to Universal Pictures.

In the late 1930s, UA turned a profit. Goldwyn was providing most of the output for distribution. Goldwyn sued United several times for disputed compensation leading Goldwyn to leave. MGM's 1939 hit Gone with the Wind was supposed to be a UA release except that Selznick wanted Clark Gable, who was under contract to MGM, to play Rhett Butler. Also that year Fairbanks died.[5]

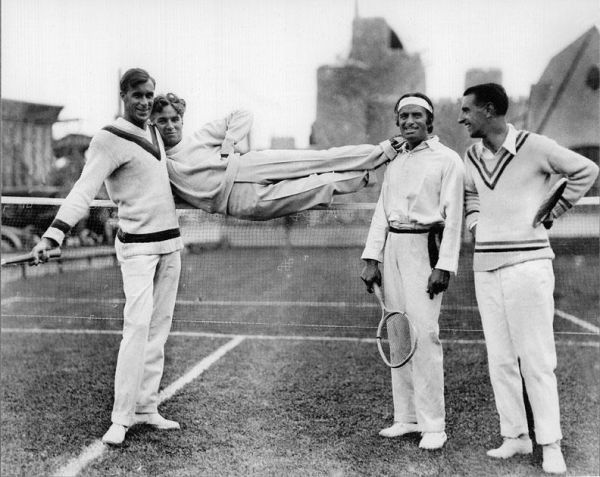

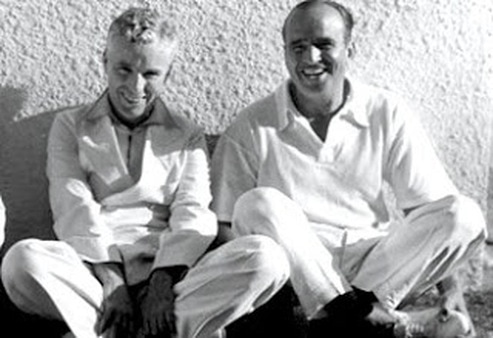

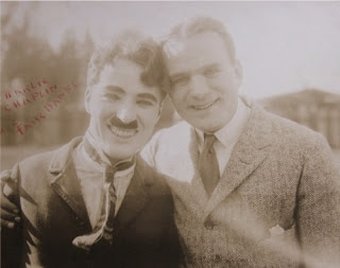

STAR FRIENDS: CHARLIE CHAPLIN AND DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS SR.

Reportedly while walking down the Hollywood Boulevard one day, Charlie Chaplin saw a large poster in front of a movie theater that announced a new film comedy in which Douglas Fairbanks played.

There was a young man standing there, and Chaplin asked him:

- Hey, have you seen this movie?

- Of course! – the young stranger answered.

- Is it funny? – asked Chaplin.- What a stupid question. I died laughing. Fairbanks is the best.

- Is he good like Chaplin?

- Much better than that wretched Chaplin, for whom I only feel pity. – continued the young man.

- If so, let me introduce myself. I am Charlie Chaplin! – Chaplin angrily exclaimed.

- I am pleased to meet you. I am Douglas Fairbanks!

After this unusual acquaintance, Chaplin and Fairbanks became very good friends. During World War I, they teamed up with Mary Pickford and toured the country at rallies to help sell Liberty bonds to help finance the war effort. The two even decided to form their own motion picture studio together, along with Pickford and director D.W. Griffith. That studio, United Artists, in one form or another continued to exist to this very day (although the current United Artists is pretty much just connected by the name only)!

The duo remained friends, even when Fairbanks's movie career started to slide in the early 1930s. On December 12, 1939, at 56, Fairbanks had a heart attack in his sleep and died a day later at his home in Santa Monica. By some accounts he had been obsessively working out against medical advice, trying to regain his once-trim waistline. Fairbanks's famous last words were, "I've never felt better". His funeral service was held at the Wee Kirk o' the Heather Church in Glendale's Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery where he was placed in a crypt in the Great Mausoleum. He was deeply mourned and honored by his colleagues and fans for his contributions to the film industry and Hollywood. A monument was erected at the cemetery, and Charlie Chaplin read a rememberance of his friend in October of 1941 at its dedication. It has often been said that Chaplin never recovered completely after the death of his friend, but what is truly known about these two friends is they liked to work hard and play ever harder...

Reportedly while walking down the Hollywood Boulevard one day, Charlie Chaplin saw a large poster in front of a movie theater that announced a new film comedy in which Douglas Fairbanks played.

There was a young man standing there, and Chaplin asked him:

- Hey, have you seen this movie?

- Of course! – the young stranger answered.

- Is it funny? – asked Chaplin.- What a stupid question. I died laughing. Fairbanks is the best.

- Is he good like Chaplin?

- Much better than that wretched Chaplin, for whom I only feel pity. – continued the young man.

- If so, let me introduce myself. I am Charlie Chaplin! – Chaplin angrily exclaimed.

- I am pleased to meet you. I am Douglas Fairbanks!

After this unusual acquaintance, Chaplin and Fairbanks became very good friends. During World War I, they teamed up with Mary Pickford and toured the country at rallies to help sell Liberty bonds to help finance the war effort. The two even decided to form their own motion picture studio together, along with Pickford and director D.W. Griffith. That studio, United Artists, in one form or another continued to exist to this very day (although the current United Artists is pretty much just connected by the name only)!

The duo remained friends, even when Fairbanks's movie career started to slide in the early 1930s. On December 12, 1939, at 56, Fairbanks had a heart attack in his sleep and died a day later at his home in Santa Monica. By some accounts he had been obsessively working out against medical advice, trying to regain his once-trim waistline. Fairbanks's famous last words were, "I've never felt better". His funeral service was held at the Wee Kirk o' the Heather Church in Glendale's Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery where he was placed in a crypt in the Great Mausoleum. He was deeply mourned and honored by his colleagues and fans for his contributions to the film industry and Hollywood. A monument was erected at the cemetery, and Charlie Chaplin read a rememberance of his friend in October of 1941 at its dedication. It has often been said that Chaplin never recovered completely after the death of his friend, but what is truly known about these two friends is they liked to work hard and play ever harder...