Ultimately, Vertigo is a love story about obsession and what humans are capable of becoming.

Storyline

John "Scottie" Ferguson is a retired San Francisco police detective who suffers from acrophobia and Madeleine is the lady who leads him to high places. A wealthy shipbuilder who is an acquaintance from college days approaches Scottie and asks him to follow his beautiful wife, Madeleine. He fears she is going insane, maybe even contemplating suicide, he believes she is possessed by a dead ancestor. Scottie is skeptical, but agrees after he sees the beautiful Madeleine.

John "Scottie" Ferguson is a retired San Francisco police detective who suffers from acrophobia and Madeleine is the lady who leads him to high places. A wealthy shipbuilder who is an acquaintance from college days approaches Scottie and asks him to follow his beautiful wife, Madeleine. He fears she is going insane, maybe even contemplating suicide, he believes she is possessed by a dead ancestor. Scottie is skeptical, but agrees after he sees the beautiful Madeleine.

Cast

James Stewart...John 'Scottie' Ferguson

Kim Novak...Madeleine Elster / Judy Barton

Barbara Bel Geddes...Midge Wood

Tom Helmore...Gavin Elster

Henry Jones...Coroner

Raymond Bailey...Scottie's Doctor

Ellen Corby...Manager of McKittrick Hotel

James Stewart...John 'Scottie' Ferguson

Kim Novak...Madeleine Elster / Judy Barton

Barbara Bel Geddes...Midge Wood

Tom Helmore...Gavin Elster

Henry Jones...Coroner

Raymond Bailey...Scottie's Doctor

Ellen Corby...Manager of McKittrick Hotel

VERTIGO INTRODUCTION

Release Year: 1958

Genre: Mystery, Romance, Thriller

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Writer: Alec Coppel, Samuel Taylor; Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac (novel)

Stars: James Stewart, Kim Novak

Spoiler below!

Is it true… blondes have more fun?

Not in Vertigo, they don't.

In Alfred Hitchcock's classic story of erotic obsession, Hitch's famously cool and elegant blondes are degraded, abandoned, murdered, and driven to suicide.

Basically the opposite of fun.

Vertigo is a psychological thriller about love and loss, guilt and obsession, desire and deceit, memory and madness. Our hero—and believe us, we're using that term very, very loosely—is John "Scottie" Ferguson, retired from the San Francisco police force after nearly falling to his death during a rooftop chase and watching a fellow officer die trying to save him. Left with a crippling case of acrophobia (fear of heights) and vertigo (dizziness), he's crushed with guilt and struggling to put his life back together.

Scottie's asked, as a favor, to investigate a friend's beautiful but death-obsessed wife, possessed by the spirit of her suicidal great-grandmother and having an annoying tendency to disappear and go into trances. Scottie's going to follow her for a few days and see where she's been going. Alright, so this is gonna be a mystery movie, right, or a ghost story, maybe?

Nope.

Scottie falls passionately in lust with this gorgeous but troubled woman. However, under the spell of great-grandma, she throws herself from a bell tower in an old Spanish mission that she's seen during her trances. Scottie ends up in a mental hospital, tortured again by guilt because his acrophobia and vertigo kept him from following her up the bell tower stairs and saving her. His attempt to "resurrect" his dead lover by recreating her in another woman ends again in tragedy, as Scottie realizes he's been the victim of a devastating deception and an unwitting accomplice to a murder.

At its 1958 release (premiering in San Francisco, fittingly), the film garnered a collective "meh" at best. It was "too slow and too long" (Variety); The New Yorker called it "far-fetched nonsense (source). It barely broke even at the box office. It wasn't what people expected from Hitchcock, master of the macabre. Audiences didn't quite know what to do with this plunge into the darkest recesses of sexual obsession and romantic delusion. They developed their own case of vertigo as they tried to make sense of the convoluted plot and sudden shifts in time and perspective.

The film grew in popularity and critical esteem over the years, though, climbing up the AFI's list of Greatest American Films (#61 in 1998, #9 in 2008), and getting a complete restoration in 1996, including surround sound and 70 mm format (source). In 2012, Vertigo did the impossible: it knocked Citizen Kane from the top spot on BFI's list of Fifty Greatest Films of All Time, a slot it had held for fifty years. Fifty. Years.

One last thing: Vertigo is also a movie about the movies—about the relationship between the creator and the image created, and the voyeuristic nature of watching films. Leading lady Kim Novak, who played the character forced into submitting to a make-over by the obsessed Scottie, told an interviewer, "It was the opportunity to express what was going on between me and Hollywood" as she learned to take direction and become what Hitchcock wanted her to be (source).

It's all very meta.

Welcome to Hitchcock.

Release Year: 1958

Genre: Mystery, Romance, Thriller

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Writer: Alec Coppel, Samuel Taylor; Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac (novel)

Stars: James Stewart, Kim Novak

Spoiler below!

Is it true… blondes have more fun?

Not in Vertigo, they don't.

In Alfred Hitchcock's classic story of erotic obsession, Hitch's famously cool and elegant blondes are degraded, abandoned, murdered, and driven to suicide.

Basically the opposite of fun.

Vertigo is a psychological thriller about love and loss, guilt and obsession, desire and deceit, memory and madness. Our hero—and believe us, we're using that term very, very loosely—is John "Scottie" Ferguson, retired from the San Francisco police force after nearly falling to his death during a rooftop chase and watching a fellow officer die trying to save him. Left with a crippling case of acrophobia (fear of heights) and vertigo (dizziness), he's crushed with guilt and struggling to put his life back together.

Scottie's asked, as a favor, to investigate a friend's beautiful but death-obsessed wife, possessed by the spirit of her suicidal great-grandmother and having an annoying tendency to disappear and go into trances. Scottie's going to follow her for a few days and see where she's been going. Alright, so this is gonna be a mystery movie, right, or a ghost story, maybe?

Nope.

Scottie falls passionately in lust with this gorgeous but troubled woman. However, under the spell of great-grandma, she throws herself from a bell tower in an old Spanish mission that she's seen during her trances. Scottie ends up in a mental hospital, tortured again by guilt because his acrophobia and vertigo kept him from following her up the bell tower stairs and saving her. His attempt to "resurrect" his dead lover by recreating her in another woman ends again in tragedy, as Scottie realizes he's been the victim of a devastating deception and an unwitting accomplice to a murder.

At its 1958 release (premiering in San Francisco, fittingly), the film garnered a collective "meh" at best. It was "too slow and too long" (Variety); The New Yorker called it "far-fetched nonsense (source). It barely broke even at the box office. It wasn't what people expected from Hitchcock, master of the macabre. Audiences didn't quite know what to do with this plunge into the darkest recesses of sexual obsession and romantic delusion. They developed their own case of vertigo as they tried to make sense of the convoluted plot and sudden shifts in time and perspective.

The film grew in popularity and critical esteem over the years, though, climbing up the AFI's list of Greatest American Films (#61 in 1998, #9 in 2008), and getting a complete restoration in 1996, including surround sound and 70 mm format (source). In 2012, Vertigo did the impossible: it knocked Citizen Kane from the top spot on BFI's list of Fifty Greatest Films of All Time, a slot it had held for fifty years. Fifty. Years.

One last thing: Vertigo is also a movie about the movies—about the relationship between the creator and the image created, and the voyeuristic nature of watching films. Leading lady Kim Novak, who played the character forced into submitting to a make-over by the obsessed Scottie, told an interviewer, "It was the opportunity to express what was going on between me and Hollywood" as she learned to take direction and become what Hitchcock wanted her to be (source).

It's all very meta.

Welcome to Hitchcock.

WHY SHOULD We CARE?

Everyone knows that Alfred Hitchcock was the Master of Suspense. The Birds—terrifying. Dial M for Murder—creepy. Psycho—we can't even. Trained during the silent film era, he created films using innovative camera and lighting techniques that kept his audiences on the edge of their seats. He could do chases, comedy, and slasher scenes with the best of 'em, but what Hitchcock really loved to do was to explore human psychology in all its weirdness and complexity. Voyeurism, fetishism, obsession, treachery—Hitchcock loved them all, and they all come together in Vertigo.

It's a neat trick: we think we're watching an eerie mystery movie, but we're really getting schooled in some ideas about what it means to fall in love with an illusion.

The film makes us 'fess up to all those fantasies we create and those stories we tell ourselves. We probably never fell in love with someone possessed by a ghost, but we may have fallen in love with someone we hardly knew. We've hopefully never made our new GF/BF dye their hair and dress exactly like our ex, but we've probably wished they could be a little more like someone else at times. We all know what it's like to want to be loved for ourselves and how hard it can be to try to be who we're not just to get someone to notice us. We all know guilt and loss, unfortunately.

Vertigo's plot may be, as the New Yorker said in 1958, far-fetched; hopefully we'll never find ourselves hanging between life and death as our hands slowly slip off a gutter ten stories about the street.

The psychological themes, though? We can relate.

Everyone knows that Alfred Hitchcock was the Master of Suspense. The Birds—terrifying. Dial M for Murder—creepy. Psycho—we can't even. Trained during the silent film era, he created films using innovative camera and lighting techniques that kept his audiences on the edge of their seats. He could do chases, comedy, and slasher scenes with the best of 'em, but what Hitchcock really loved to do was to explore human psychology in all its weirdness and complexity. Voyeurism, fetishism, obsession, treachery—Hitchcock loved them all, and they all come together in Vertigo.

It's a neat trick: we think we're watching an eerie mystery movie, but we're really getting schooled in some ideas about what it means to fall in love with an illusion.

The film makes us 'fess up to all those fantasies we create and those stories we tell ourselves. We probably never fell in love with someone possessed by a ghost, but we may have fallen in love with someone we hardly knew. We've hopefully never made our new GF/BF dye their hair and dress exactly like our ex, but we've probably wished they could be a little more like someone else at times. We all know what it's like to want to be loved for ourselves and how hard it can be to try to be who we're not just to get someone to notice us. We all know guilt and loss, unfortunately.

Vertigo's plot may be, as the New Yorker said in 1958, far-fetched; hopefully we'll never find ourselves hanging between life and death as our hands slowly slip off a gutter ten stories about the street.

The psychological themes, though? We can relate.

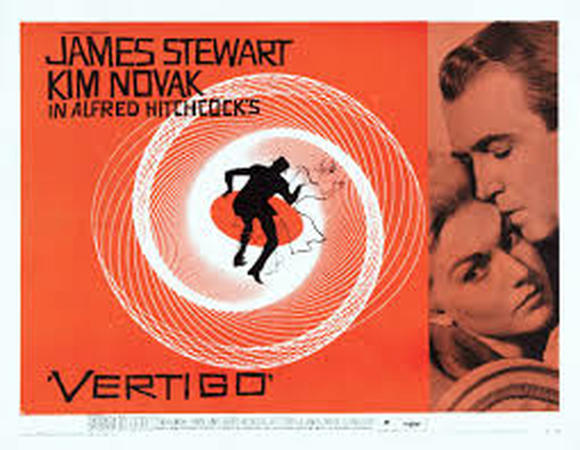

Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo might have been a critical disappointment when it came out in 1958, but it definitely had one of the most eye-catching poster designs in cinema history.

The poster was designed by Saul Bass who also did the movie’s groundbreaking title sequence. It features hand-drawn male and female figures that are standing before a massive white spiral against a striking orange background. It might be one of the few movie posters out there that you can identify from 100 yards away.

Vertigo played around the world and, as you can see below, the movie’s poster changed greatly to appeal to a local audience. The differences are fascinating.

English-speaking countries tended to keep Bass’s spiral while foreign-language markets largely did not. The Japanese poster plays up the romantic elements of Vertigo while the Italian poster focuses on the psychological weirdness of the movie. And the Polish poster – which ditches all references to Saul Bass’s design and, really, anything from the film itself – is pretty damned awesome.

Of course, in the years since Vertigo’s release, its reputation has only grown. And in a 2012, Sight and Sound magazine put Vertigo at the top of their list for Greatest Films of All Time, unseating Citizen Kane. Maybe the poster had something to do with that.

The poster was designed by Saul Bass who also did the movie’s groundbreaking title sequence. It features hand-drawn male and female figures that are standing before a massive white spiral against a striking orange background. It might be one of the few movie posters out there that you can identify from 100 yards away.

Vertigo played around the world and, as you can see below, the movie’s poster changed greatly to appeal to a local audience. The differences are fascinating.

English-speaking countries tended to keep Bass’s spiral while foreign-language markets largely did not. The Japanese poster plays up the romantic elements of Vertigo while the Italian poster focuses on the psychological weirdness of the movie. And the Polish poster – which ditches all references to Saul Bass’s design and, really, anything from the film itself – is pretty damned awesome.

Of course, in the years since Vertigo’s release, its reputation has only grown. And in a 2012, Sight and Sound magazine put Vertigo at the top of their list for Greatest Films of All Time, unseating Citizen Kane. Maybe the poster had something to do with that.

What Makes Vertigo the Best Film of All Time? Four Video Essays (and Martin Scorsese) Explain

September 7th, 2016

Vertigo is the greatest motion picture of all time. Or so say the results of the latest round of respected film magazine Sight & Sound‘s long-running critics poll, in which Alfred Hitchcock’s James Stewart- and Kim Novak- (and San Francisco-) starring psychological thriller unseated Citizen Kane from the top spot. For half a century, Orson Welles’ directorial debut seemed like it would forever occupy the head of the cinematic table, its status disputed only by the unimpressed modern viewers who, having attended a revival screening or happened across it on television, complain that they don’t understand all the critical fuss. The new champion has given them a different question to ask: what makes Vertigo so great, anyway?

Like Citizen Kane in 1941, Vertigo flopped at the box office in 1958, but Hitchcock’s film drew more negative reviews, its critics sounding baffled, dismissive, or both. Even Welles reportedly disliked it, and Hitchcock kept it out of circulation himself between 1973 and his death in 1980, a period when cinephiles — and cinephile-filmmakers, such as a certain well-known Vertigo enthusiast called Martin Scorsese — regarded it as a sacred document. Only in 1984 did Vertigo re-emerge, by which point it badly needed an extensive audiovisual restoration. It received just that in 1996, speeding up its ascent to acclaim, in progress at least since it first appeared on the Sight & Sound poll, in eighth place, in 1982.

“Why, after watching Vertigo more than, say, 30 times, are we confident that there are things to discover in it — that some aspects remain ambiguous and uncertain, unfathomably complex, even if we scrutinize every look, every cut, every movement of the camera?” asks critic Miguel Marías in an essay on the film at Sight & Sound. He lists many reasons, and many more exist than that. But nobody can appreciate a work with so many purely cinematic strengths without actually watching it, which perhaps makes the video essay a better form for examining the power of what we have come to recognize as Hitchcock’s masterpiece.

“Only one film had been capable of portraying impossible memory — insane memory,” says the narrator of Chris Marker’s essay film Sans Soleil: “Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo.” B. Kite and Alexander Points-Zollo’s three-part “Vertigo Variations” at the Museum of the Moving Image uses Marker’s interpretation, as well as many others, to see from as many angles as possible Hitchcock’s “impossible object: a gimcrack plot studded with strange gaps that nonetheless rides a pulse of peculiar necessity, a field of association that simultaneously expands and contracts like its famous trick shot, a ghost story whose spirits linger even after having been apparently explained away, and a study of obsession that becomes an obsessive object in its own right.”

The popular explainer known as the Nerdwriter looks at how Hitchcock blocks a scene by breaking down the visit by Stewart’s traumatized, retired police detective protagonist to the office of a former college classmate turned shipbuilding magnate. The conversation they have sets the story in motion, and Hitchcock took the placement of his actors and his camera in each and every shot as seriously as he took every other aspect of the film. Color, for instance: another video essayist, working under the banner of Society of Geeks, identifies Hitchcock’s use of rich Technicolor as a mechanism to heighten the emotions, with, as critic Jim Emerson writes it, “red suggesting Scottie’s fear/caution/hesitancy when it comes to romance, and its opposite green, suggesting the Edenic bliss (and/or watery oblivion) of his infatuation.” Ava Burke isolates another of Hitchcock’s visual devices in use: the mirroring that fills the viewing experience with visual echoes both faint and loud.

When he got to work on Vertigo, Hitchcock had already made more than forty films in just over three decades as a filmmaker. Though often labeled a “master of suspense” during his lifetime, he instinctively learned and deeply internalized a vast range of filmmaking techniques that film scholars, as well as his successors in filmmaking, continue to take apart, scrutinize, and put back together again. This most re-watchable of his pictures (and one that, according to several of the critics and video essayists here, transforms utterly upon the second viewing) makes use of the full spectrum of Hitchcock’s mastery as well as the full spectrum of his fixations. Whether or not you consider it the greatest motion picture of all time, if you love the art of cinema, you by definition love Vertigo.

September 7th, 2016

Vertigo is the greatest motion picture of all time. Or so say the results of the latest round of respected film magazine Sight & Sound‘s long-running critics poll, in which Alfred Hitchcock’s James Stewart- and Kim Novak- (and San Francisco-) starring psychological thriller unseated Citizen Kane from the top spot. For half a century, Orson Welles’ directorial debut seemed like it would forever occupy the head of the cinematic table, its status disputed only by the unimpressed modern viewers who, having attended a revival screening or happened across it on television, complain that they don’t understand all the critical fuss. The new champion has given them a different question to ask: what makes Vertigo so great, anyway?

Like Citizen Kane in 1941, Vertigo flopped at the box office in 1958, but Hitchcock’s film drew more negative reviews, its critics sounding baffled, dismissive, or both. Even Welles reportedly disliked it, and Hitchcock kept it out of circulation himself between 1973 and his death in 1980, a period when cinephiles — and cinephile-filmmakers, such as a certain well-known Vertigo enthusiast called Martin Scorsese — regarded it as a sacred document. Only in 1984 did Vertigo re-emerge, by which point it badly needed an extensive audiovisual restoration. It received just that in 1996, speeding up its ascent to acclaim, in progress at least since it first appeared on the Sight & Sound poll, in eighth place, in 1982.

“Why, after watching Vertigo more than, say, 30 times, are we confident that there are things to discover in it — that some aspects remain ambiguous and uncertain, unfathomably complex, even if we scrutinize every look, every cut, every movement of the camera?” asks critic Miguel Marías in an essay on the film at Sight & Sound. He lists many reasons, and many more exist than that. But nobody can appreciate a work with so many purely cinematic strengths without actually watching it, which perhaps makes the video essay a better form for examining the power of what we have come to recognize as Hitchcock’s masterpiece.

“Only one film had been capable of portraying impossible memory — insane memory,” says the narrator of Chris Marker’s essay film Sans Soleil: “Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo.” B. Kite and Alexander Points-Zollo’s three-part “Vertigo Variations” at the Museum of the Moving Image uses Marker’s interpretation, as well as many others, to see from as many angles as possible Hitchcock’s “impossible object: a gimcrack plot studded with strange gaps that nonetheless rides a pulse of peculiar necessity, a field of association that simultaneously expands and contracts like its famous trick shot, a ghost story whose spirits linger even after having been apparently explained away, and a study of obsession that becomes an obsessive object in its own right.”

The popular explainer known as the Nerdwriter looks at how Hitchcock blocks a scene by breaking down the visit by Stewart’s traumatized, retired police detective protagonist to the office of a former college classmate turned shipbuilding magnate. The conversation they have sets the story in motion, and Hitchcock took the placement of his actors and his camera in each and every shot as seriously as he took every other aspect of the film. Color, for instance: another video essayist, working under the banner of Society of Geeks, identifies Hitchcock’s use of rich Technicolor as a mechanism to heighten the emotions, with, as critic Jim Emerson writes it, “red suggesting Scottie’s fear/caution/hesitancy when it comes to romance, and its opposite green, suggesting the Edenic bliss (and/or watery oblivion) of his infatuation.” Ava Burke isolates another of Hitchcock’s visual devices in use: the mirroring that fills the viewing experience with visual echoes both faint and loud.

When he got to work on Vertigo, Hitchcock had already made more than forty films in just over three decades as a filmmaker. Though often labeled a “master of suspense” during his lifetime, he instinctively learned and deeply internalized a vast range of filmmaking techniques that film scholars, as well as his successors in filmmaking, continue to take apart, scrutinize, and put back together again. This most re-watchable of his pictures (and one that, according to several of the critics and video essayists here, transforms utterly upon the second viewing) makes use of the full spectrum of Hitchcock’s mastery as well as the full spectrum of his fixations. Whether or not you consider it the greatest motion picture of all time, if you love the art of cinema, you by definition love Vertigo.

If you’ve made a film, you’ll remember when you realized that editing, more than any other stage of production, determines the audience’s final experience. “The first films ever made were shot in one take,” wrote the late, always editing-conscious Roger Ebert, reviewing Mike Figgis’ Time Code. “Just about everybody agrees that the introduction of editing was an improvement.” Figgis’ film tried to do without editing, successfully to my mind, not so successfully to Ebert’s. Later, the critic openly loathed Vincent Gallo’s traditionally edited The Brown Bunny, but his opinion turned almost 180 degrees when the director re-edited the movie, strategically cutting 26 minutes. “It is said that editing is the soul of the cinema,” Ebert wrote of the revision. “In the case of The Brown Bunny, it is its salvation.” Yet the impulse to create a wholly unedited film still occasionally grabs a major filmmaker, and not all of them wind up remaking Andy Warhol’s eight-hour still shot Empire.

Some of these pictures, thanks to well-placed cuts and clever camera movements, only look unedited. The best-known of these comes from no less a craftsman than Alfred Hitchcock, who built 1948’s Rope out of ten seemingly cut-free segments, each internal splice meticulously disguised. Twelve years later, he would make his most overt and memorable use of editing in Psycho. In the clip at the top of this post, Hitchcock himself explains the importance of editing — or, in his preferred term, assembly. He breaks down the structure of Psycho‘s famous shower scene. “Now, as you know, you could not take the camera and just show a nude woman being stabbed to death. It had to be done impressionistically. It was done with little pieces of the film: the head, the hand, parts of the torso, shadow on the curtain, the shower itself. In that scene there were 78 pieces of film in about 45 seconds.” Say what you will about the content-restricting Hays Code; its limitations could sometimes drive to new heights the visual creativity of our best cinematic minds.

Some of these pictures, thanks to well-placed cuts and clever camera movements, only look unedited. The best-known of these comes from no less a craftsman than Alfred Hitchcock, who built 1948’s Rope out of ten seemingly cut-free segments, each internal splice meticulously disguised. Twelve years later, he would make his most overt and memorable use of editing in Psycho. In the clip at the top of this post, Hitchcock himself explains the importance of editing — or, in his preferred term, assembly. He breaks down the structure of Psycho‘s famous shower scene. “Now, as you know, you could not take the camera and just show a nude woman being stabbed to death. It had to be done impressionistically. It was done with little pieces of the film: the head, the hand, parts of the torso, shadow on the curtain, the shower itself. In that scene there were 78 pieces of film in about 45 seconds.” Say what you will about the content-restricting Hays Code; its limitations could sometimes drive to new heights the visual creativity of our best cinematic minds.

Proudly powered by Weebly