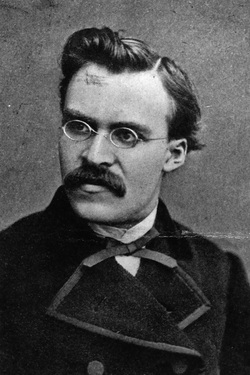

Friedrich Nietzsche

Ever wonder how famous philosophers from the past spent their many hours of tedium between paradigm-smashing epiphanies? I do. And I have learned much from the biographical morsels on “Daily Routines,” a blog about “How writers, artists, and other interesting people organize their days.” (The blog has also now yielded a book.) While there is much fascinating variety to be found among these descriptions of the quotidian habits of celebrity humanists, one quote found on the site from V.S. Pritchett stands out: “Sooner or later, the great men turn out to be all alike. They never stop working. They never lose a minute. It is very depressing.” But I urge you, be not depressed. In these précis of the mundane lives of philosophers and artists, we find no small amount of meditative leisure occupying every day. Read these tiny biographies and be edified. The contemplative life requires discipline and hard work, for sure. But it also seems to require some time indulging carnal pleasures and much more time lost in thought.

Let’s take Friedrich Nietzsche (above). While most of us couldn’t possibly reach the great heights of iconoclastic solitude he scaled—and I’m not sure that we would want to—we might find his daily balance of the kinetic, aesthetic, gustatory, and contemplative worth aiming at. Though not featured on Daily Routines, an excerpt from Curtis Cate’s eponymous Nietzsche biography shows us the curious habits of this most curious man:

With a Spartan rigour which never ceased to amaze his landlord-grocer, Nietzsche would get up every morning when the faintly dawning sky was still grey, and, after washing himself with cold water from the pitcher and china basin in his bedroom and drinking some warm milk, he would, when not felled by headaches and vomiting, work uninterruptedly until eleven in the morning. He then went for a brisk, two-hour walk through the nearby forest or along the edge of Lake Silvaplana (to the north-east) or of Lake Sils (to the south-west), stopping every now and then to jot down his latest thoughts in the notebook he always carried with him. Returning for a late luncheon at the Hôtel Alpenrose, Nietzsche, who detested promiscuity, avoided the midday crush of the table d’hôte in the large dining-room and ate a more or less ‘private’ lunch, usually consisting of a beefsteak and an ‘unbelievable’ quantity of fruit, which was, the hotel manager was persuaded, the chief cause of his frequent stomach upsets. After luncheon, usually dressed in a long and somewhat threadbare brown jacket, and armed as usual with notebook, pencil, and a large grey-green parasol to shade his eyes, he would stride off again on an even longer walk, which sometimes took him up the Fextal as far as its majestic glacier. Returning ‘home’ between four and five o’clock, he would immediately get back to work, sustaining himself on biscuits, peasant bread, honey (sent from Naumburg), fruit and pots of tea he brewed for himself in the little upstairs ‘dining-room’ next to his bedroom, until, worn out, he snuffed out the candle and went to bed around 11 p.m.

This comes to us via A Piece of Monologue, who also provide some photographs of Nietzsche’s favorite Swiss vistas and his austere accommodations. No doubt this life, however lonely, led to the production of some of the most world-shaking philosophical texts ever produced, perhaps rivaled in the nineteenth century only by the work of the prodigious Karl Marx.

Let’s take Friedrich Nietzsche (above). While most of us couldn’t possibly reach the great heights of iconoclastic solitude he scaled—and I’m not sure that we would want to—we might find his daily balance of the kinetic, aesthetic, gustatory, and contemplative worth aiming at. Though not featured on Daily Routines, an excerpt from Curtis Cate’s eponymous Nietzsche biography shows us the curious habits of this most curious man:

With a Spartan rigour which never ceased to amaze his landlord-grocer, Nietzsche would get up every morning when the faintly dawning sky was still grey, and, after washing himself with cold water from the pitcher and china basin in his bedroom and drinking some warm milk, he would, when not felled by headaches and vomiting, work uninterruptedly until eleven in the morning. He then went for a brisk, two-hour walk through the nearby forest or along the edge of Lake Silvaplana (to the north-east) or of Lake Sils (to the south-west), stopping every now and then to jot down his latest thoughts in the notebook he always carried with him. Returning for a late luncheon at the Hôtel Alpenrose, Nietzsche, who detested promiscuity, avoided the midday crush of the table d’hôte in the large dining-room and ate a more or less ‘private’ lunch, usually consisting of a beefsteak and an ‘unbelievable’ quantity of fruit, which was, the hotel manager was persuaded, the chief cause of his frequent stomach upsets. After luncheon, usually dressed in a long and somewhat threadbare brown jacket, and armed as usual with notebook, pencil, and a large grey-green parasol to shade his eyes, he would stride off again on an even longer walk, which sometimes took him up the Fextal as far as its majestic glacier. Returning ‘home’ between four and five o’clock, he would immediately get back to work, sustaining himself on biscuits, peasant bread, honey (sent from Naumburg), fruit and pots of tea he brewed for himself in the little upstairs ‘dining-room’ next to his bedroom, until, worn out, he snuffed out the candle and went to bed around 11 p.m.

This comes to us via A Piece of Monologue, who also provide some photographs of Nietzsche’s favorite Swiss vistas and his austere accommodations. No doubt this life, however lonely, led to the production of some of the most world-shaking philosophical texts ever produced, perhaps rivaled in the nineteenth century only by the work of the prodigious Karl Marx.