S H A K E S P E A R E

74 Ways Characters Die in Shakespeare’s Plays Shown in a Handy Infographic: From Snakebites to Lack of Sleep in Literature, Theatre | January 1st, 2016

In the graduate department where I once taught freshmen and sophomores the rudiments of college English, it became common practice to include Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus on many an Intro to Lit syllabus, along with a viewing of Julie Taymor’s flamboyant film adaptation. The early work is thought to be Shakespeare’s first tragedy, cobbled together from popular Roman histories and Elizabethan revenge plays. And it is a truly bizarre play, swinging wildly in tone from classical tragedy, to satirical dark humor, to comic farce, and back to tragedy again. Critic Harold Bloom called Titus “an exploitative parody” of the very popular revenge tragedies of the time—its murders, maimings, rapes, and mutilations pile up, scene upon scene, and leave characters and readers/audiences reeling in grief and disbelief from the shocking body count.

Part of the fun of teaching Titus is in watching students’ jaws drop as they realize just how bloody-minded the Bard is. While Taymor’s adaptation takes many modern liberties in costuming, music, and set design, its horror-show depiction of Titus’ unrelenting mayhem is faithful to the text. Later, more mature plays reign in the excessive black comedy and shock factor, but the bodies still abound. As accustomed as we are to thinking of contemporary entertainments like Game of Thrones as especially gratuitous, the whole of Shakespeare’s corpus, writes Alice Vincent at The Telegraph is “more gory” than even HBO’s squirm-worthy fantasy epic, featuring a total of 74 deaths in 37 plays to Game of Thrones’ 61 in 50 episodes.

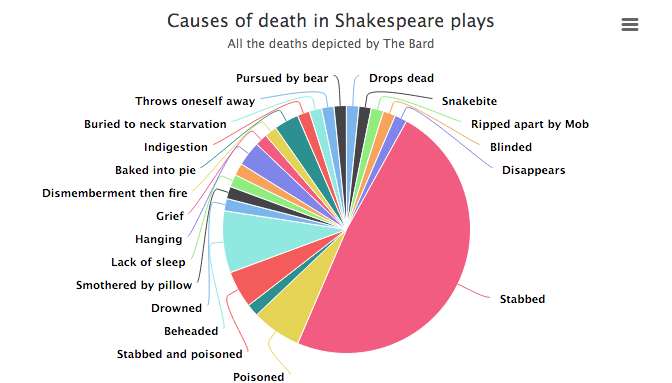

All of those various demises will now come together in a compendium play being staged at The Globe (in London) called The Complete Deaths. It will include everything “from early rapier thrusts to the more elaborate viper-breast application adopted by Cleopatra.” The only death director Tim Crouch has excluded is “that of a fly that meets a sticky end in Titus Andronicus.” In the infographic above, see all of the causes of those deaths, including Antony and Cleopatra’s snakebite and Titus Andronicus’ piece-de-resistance, “baked in a pie.”

Part of the reason so many of my former undergraduate students found Shakespeare’s brutality shocking and unexpected has to do with the way his work was tamed by later 17th and 18th century critics, who “didn’t approve of the on-stage gore.” The Telegraph quotes director of the Shakespeare Institute Michael Dobson, who points out that Elizabethan drama was especially gruesome; “the English drama was notorious for on-stage deaths,” and all of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, including Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson, wrote violent scenes that can still turn our stomachs.

Recent productions like a bloody staging of Titus at The Globe in 2014 are restoring the gore in Shakespeare’s work, and The Complete Deaths will leave audiences with little doubt that Shakespeare’s culture was as permeated with representations of violence as our own—and it was as much, if not more so, plagued by the real thing.

In the graduate department where I once taught freshmen and sophomores the rudiments of college English, it became common practice to include Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus on many an Intro to Lit syllabus, along with a viewing of Julie Taymor’s flamboyant film adaptation. The early work is thought to be Shakespeare’s first tragedy, cobbled together from popular Roman histories and Elizabethan revenge plays. And it is a truly bizarre play, swinging wildly in tone from classical tragedy, to satirical dark humor, to comic farce, and back to tragedy again. Critic Harold Bloom called Titus “an exploitative parody” of the very popular revenge tragedies of the time—its murders, maimings, rapes, and mutilations pile up, scene upon scene, and leave characters and readers/audiences reeling in grief and disbelief from the shocking body count.

Part of the fun of teaching Titus is in watching students’ jaws drop as they realize just how bloody-minded the Bard is. While Taymor’s adaptation takes many modern liberties in costuming, music, and set design, its horror-show depiction of Titus’ unrelenting mayhem is faithful to the text. Later, more mature plays reign in the excessive black comedy and shock factor, but the bodies still abound. As accustomed as we are to thinking of contemporary entertainments like Game of Thrones as especially gratuitous, the whole of Shakespeare’s corpus, writes Alice Vincent at The Telegraph is “more gory” than even HBO’s squirm-worthy fantasy epic, featuring a total of 74 deaths in 37 plays to Game of Thrones’ 61 in 50 episodes.

All of those various demises will now come together in a compendium play being staged at The Globe (in London) called The Complete Deaths. It will include everything “from early rapier thrusts to the more elaborate viper-breast application adopted by Cleopatra.” The only death director Tim Crouch has excluded is “that of a fly that meets a sticky end in Titus Andronicus.” In the infographic above, see all of the causes of those deaths, including Antony and Cleopatra’s snakebite and Titus Andronicus’ piece-de-resistance, “baked in a pie.”

Part of the reason so many of my former undergraduate students found Shakespeare’s brutality shocking and unexpected has to do with the way his work was tamed by later 17th and 18th century critics, who “didn’t approve of the on-stage gore.” The Telegraph quotes director of the Shakespeare Institute Michael Dobson, who points out that Elizabethan drama was especially gruesome; “the English drama was notorious for on-stage deaths,” and all of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, including Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson, wrote violent scenes that can still turn our stomachs.

Recent productions like a bloody staging of Titus at The Globe in 2014 are restoring the gore in Shakespeare’s work, and The Complete Deaths will leave audiences with little doubt that Shakespeare’s culture was as permeated with representations of violence as our own—and it was as much, if not more so, plagued by the real thing.

Free Online Shakespeare Courses: Primers on the Bard from Oxford, Harvard, Berkeley & Morein Literature, Online Courses| April 7th, 2014

I had the great good fortune of having grown up just outside Washington, DC, where on a fifth grade class trip to the Folger Library and Theater, I fell in love with Shakespeare. This experience, along with a few visits to see his plays performed at nearby Wolftrap, made me think I might go into theater. Instead I became a student of literature, but somehow, my love of Shakespeare on the stage didn’t translate to the page until college. While studying for a sophomore-level “Histories & Tragedies” class, I sat, my Norton Shakespeare open, in front of the TV—reading along while watching Kenneth Branagh’s stylish film adaptation of Hamlet, which draws on the entire text of the play.

Only then came the epiphany: this language is music and magic. The rhythmic beauty, depths of feeling, humor broad and incisive, extraordinary range of human types…. If we are to believe pre-eminent Shakespeare scholar Harold Bloom, Shakespeare invented modern humanity. If this seems to go too far, he at least captured human complexity with greater inventive skill than any English writer before him, and possibly after. Is there any shame in finally “getting” Shakespeare’s language from the movies? None at all. One of the most excellent qualities of the Bard’s work—among so many reasons it endures—is its seemingly endless adaptability to every possible period, cultural context, and medium.

While engagement with any of the innumerable Shakespeare adaptations and performances promises reward, there’s little that enhances appreciation of the Bard’s work more than reading it under the tutelage of a trained scholar in the playwright’s Elizabethan language and history. Universal though he may be, Shakespeare wrote his plays in a particular time and place, under specific influences and working conditions. If you have not had the pleasure of studying the plays in a college setting—or if your memories of those long-ago English classes have faded—we offer a number of excellent free online courses from some of the finest universities. See a list below, all of which appear in our list of Free Online Literature Courses, part of our larger list of 875 Free Online Courses.

Also, speaking of the Folger, that venerable institution has just released all of Shakespeare’s plays in free, searchable online texts based on their highly-regarded scholarly print editions. And though some beg to differ, I still say you can’t go wrong with Branagh.

I had the great good fortune of having grown up just outside Washington, DC, where on a fifth grade class trip to the Folger Library and Theater, I fell in love with Shakespeare. This experience, along with a few visits to see his plays performed at nearby Wolftrap, made me think I might go into theater. Instead I became a student of literature, but somehow, my love of Shakespeare on the stage didn’t translate to the page until college. While studying for a sophomore-level “Histories & Tragedies” class, I sat, my Norton Shakespeare open, in front of the TV—reading along while watching Kenneth Branagh’s stylish film adaptation of Hamlet, which draws on the entire text of the play.

Only then came the epiphany: this language is music and magic. The rhythmic beauty, depths of feeling, humor broad and incisive, extraordinary range of human types…. If we are to believe pre-eminent Shakespeare scholar Harold Bloom, Shakespeare invented modern humanity. If this seems to go too far, he at least captured human complexity with greater inventive skill than any English writer before him, and possibly after. Is there any shame in finally “getting” Shakespeare’s language from the movies? None at all. One of the most excellent qualities of the Bard’s work—among so many reasons it endures—is its seemingly endless adaptability to every possible period, cultural context, and medium.

While engagement with any of the innumerable Shakespeare adaptations and performances promises reward, there’s little that enhances appreciation of the Bard’s work more than reading it under the tutelage of a trained scholar in the playwright’s Elizabethan language and history. Universal though he may be, Shakespeare wrote his plays in a particular time and place, under specific influences and working conditions. If you have not had the pleasure of studying the plays in a college setting—or if your memories of those long-ago English classes have faded—we offer a number of excellent free online courses from some of the finest universities. See a list below, all of which appear in our list of Free Online Literature Courses, part of our larger list of 875 Free Online Courses.

Also, speaking of the Folger, that venerable institution has just released all of Shakespeare’s plays in free, searchable online texts based on their highly-regarded scholarly print editions. And though some beg to differ, I still say you can’t go wrong with Branagh.

- Approaching Shakespeare – Free iTunes Audio – Free Online Audio –Emma Smith, Oxford

- Shakespeare After All: The Later Plays – Free Course in Multiple Formats – Marjorie Garber, Harvard

- Shakespeare’s Principal Plays – Free iTunes Audio – Free Online Audio – Ralph Williams, University of Michigan

- Survey of Shakespeare’s Plays – Free Online Audio – William Flesch, Brandeis

- Not Shakespeare: Elizabethan and Jacobean Popular Theatre –Free iTunes Audio – Free Online Audio – Multiple profs, Oxford

- Shakespeare – Free iTunes Audio – Free Online Audio – Charles Altieri, UC Berkeley