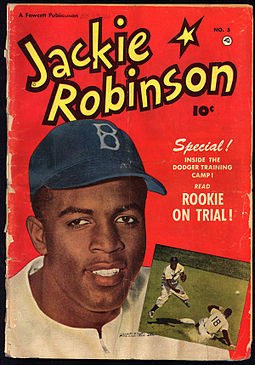

With the Dodgers from 1947 to 1956

James Boswell, 9th Laird of Auchinleck(/ˈbɒzwɛl, -wəl/; 29 October 1740 – 19 May 1795), was a Scottish biographer and diarist, born in Edinburgh. He is best known for the biography he wrote of his friend and contemporary, the English literary figure Samuel Johnson, which is commonly said to be the greatest biography written in the English language.

Click here to view Jackie Robinson's four page contract with the Dodgers:

www.phillymag.com/news/2016/05/24/jackie-robinson-contracts-constitution-center/#gallery-2-4

www.phillymag.com/news/2016/05/24/jackie-robinson-contracts-constitution-center/#gallery-2-4

42 The Jackie Robinson Story

Robinson with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1954

Second baseman

Born: January 31, 1919

Cairo, Georgia

Died: October 24, 1972 (aged 53)

Stamford, Connecticut

Batted: RightThrew: Right

MLB debut

April 15, 1947, for the Brooklyn Dodgers

Last MLB appearance

October 10, 1956, for the Brooklyn Dodgers

MLB statistics

Batting average.311

Hits1,518

Home runs137

Runs batted in734

Teams

Negro leagues

- Kansas City Monarchs (1945)

- Brooklyn Dodgers (1947–1956)

Career highlights and awards

- 6× All-Star (1949–1954)

- World Series champion (1955)

- NL MVP (1949)

- MLB Rookie of the Year (1947)

- NL batting champion (1949)

- 2× NL stolen base leader (1947, 1949)

- Jersey number 42 retired by all MLB teams

- Major League Baseball All-Century Team

Baseball Hall of Fame

Inducted1962

Vote77.5% (first ballot)

James Boswell, 9th Laird of Auchinleck (/ˈbɒzˌwɛl, -wəl/; 29 October 1740 – 19 May 1795), was a Scottishbiographer and diarist, born in Edinburgh. He is best known for the biography he wrote of one of his contemporaries, the English literary figure Samuel Johnson, which is commonly said to be the greatest biography written in the English language.[1][2]

Boswell's surname has passed into the English language as a term (Boswell, Boswellian, Boswellism) for a constant companion and observer, especially one who records those observations in print. In "A Scandal in Bohemia", Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's character Sherlock Holmes affectionately says of Dr. Watson, who narrates the tales, "I am lost without my Boswell."[3]

Boswell's surname has passed into the English language as a term (Boswell, Boswellian, Boswellism) for a constant companion and observer, especially one who records those observations in print. In "A Scandal in Bohemia", Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's character Sherlock Holmes affectionately says of Dr. Watson, who narrates the tales, "I am lost without my Boswell."[3]

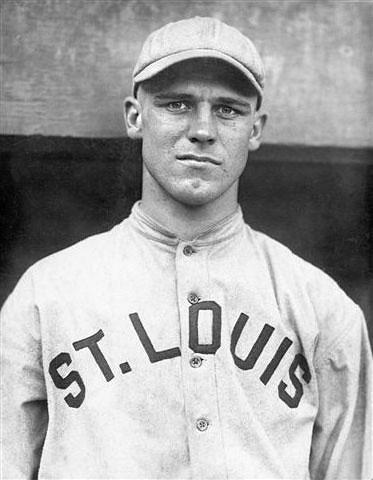

Red Barber was the Dodgers original broadcaster, calling Brooklyn Dodgers games on the radio (and later TV) from 1939-1953.

Walter Lanier "Red" Barber (February 17, 1908 – October 22, 1992) was an American sports commentator. Barber, nicknamed "The Ol' Redhead", was primarily identified with radio broadcasts of Major League Baseball, calling play-by-play across four decades with the Cincinnati Reds (1934–1938), Brooklyn Dodgers (1939–1953), and New York Yankees (1954–1966). Like his fellow sports pioneer Mel Allen, Barber also gained a niche calling college and professional American football in his primary market of New York City.

Walter Lanier "Red" Barber (February 17, 1908 – October 22, 1992) was an American sports commentator. Barber, nicknamed "The Ol' Redhead", was primarily identified with radio broadcasts of Major League Baseball, calling play-by-play across four decades with the Cincinnati Reds (1934–1938), Brooklyn Dodgers (1939–1953), and New York Yankees (1954–1966). Like his fellow sports pioneer Mel Allen, Barber also gained a niche calling college and professional American football in his primary market of New York City.

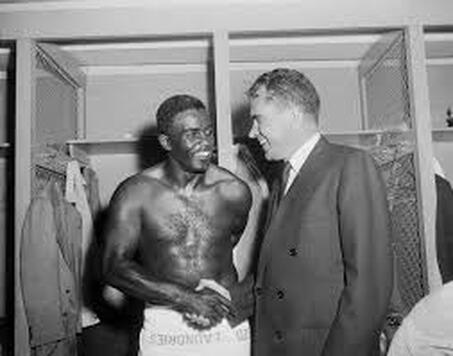

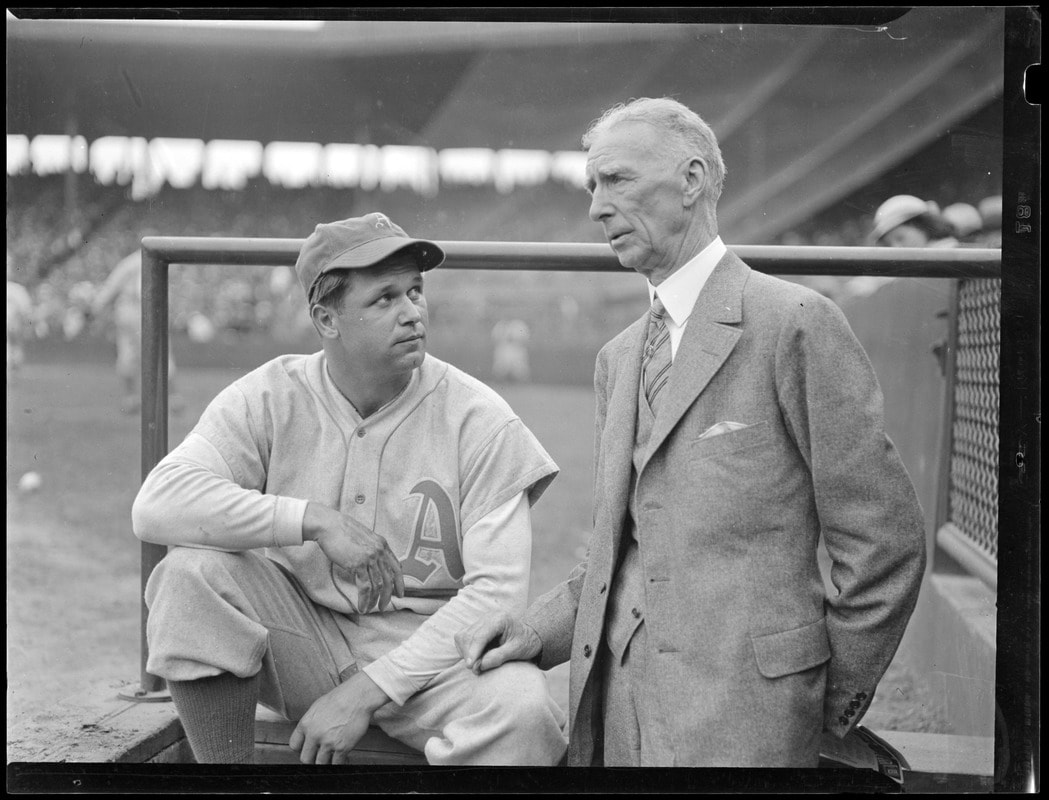

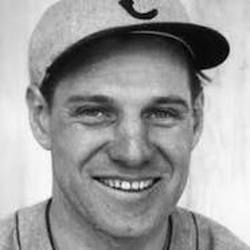

Above

Leo Durocher

Baseball player

Leo Ernest Durocher, nicknamed Leo the Lip and Lippy, was an American professional baseball player, manager and coach. He played in Major League Baseball as an infielder. Wikipedia

Born: July 27, 1905, West Springfield, MA

Died: October 7, 1991, Palm Springs, CA

Height: 5′ 10″

Spouse: Lynne Walker Goldblatt (m. 1969–1980), More

Books: The Dodgers and Me: The Inside Story, Dodgers and Me: Inside Story: American Autobiography

Quotes

Baseball is like church. Many attend, few understand.

I never questioned the integrity of an umpire. Their eyesight, yes.

You don't save a pitcher for tomorrow. Tomorrow it may rain.

Leo Durocher

Baseball player

Leo Ernest Durocher, nicknamed Leo the Lip and Lippy, was an American professional baseball player, manager and coach. He played in Major League Baseball as an infielder. Wikipedia

Born: July 27, 1905, West Springfield, MA

Died: October 7, 1991, Palm Springs, CA

Height: 5′ 10″

Spouse: Lynne Walker Goldblatt (m. 1969–1980), More

Books: The Dodgers and Me: The Inside Story, Dodgers and Me: Inside Story: American Autobiography

Quotes

Baseball is like church. Many attend, few understand.

I never questioned the integrity of an umpire. Their eyesight, yes.

You don't save a pitcher for tomorrow. Tomorrow it may rain.

On June 17, 1971, at the age of 24, he was killed in an automobile accident. The experience with his son's drug addiction turned Robinson Sr. into an avid anti-drug crusader toward the end of his life. Robinson did not long outlive his son.

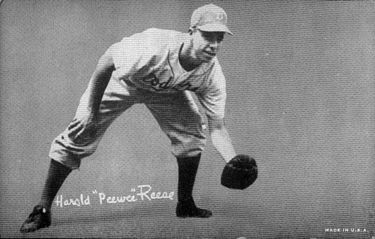

Above

Harold Peter Henry "Pee Wee" Reese (July 23, 1918 – August 14, 1999) was an American professional baseball player. He played in Major League Baseball as a shortstop for the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers from 1940 to 1958. A ten-time All Star, Reese contributed to seven National League championships for the Dodgers and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1984. Reese is also famous for his support of his teammate Jackie Robinson, the first modern African American player in the major leagues, especially in Robinson's difficult first years.

Early life Reese's nickname originated in his childhood, as he was a champion marbles player (a "pee wee" is a small marble). Reese was born in Ekron, Meade County, Kentucky, and raised there until he was nearly eight years old, when his family moved to racially segregated Louisville. In high school, Reese was so small that he did not play baseball until senior year, at which time he weighed only 120 pounds and played just six games as a second baseman. He graduated from duPont Manual High School in 1937. He worked as a cable splicer for the Louisville phone company, only playing amateur baseball in a church league. When Reese's team reached the league championship, the minor league Louisville Colonels allowed them to play the championship game on their field. Reese impressed Colonels owner Cap Neal, who signed him to a contract for a $200 bonus.

Harold Peter Henry "Pee Wee" Reese (July 23, 1918 – August 14, 1999) was an American professional baseball player. He played in Major League Baseball as a shortstop for the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers from 1940 to 1958. A ten-time All Star, Reese contributed to seven National League championships for the Dodgers and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1984. Reese is also famous for his support of his teammate Jackie Robinson, the first modern African American player in the major leagues, especially in Robinson's difficult first years.

Early life Reese's nickname originated in his childhood, as he was a champion marbles player (a "pee wee" is a small marble). Reese was born in Ekron, Meade County, Kentucky, and raised there until he was nearly eight years old, when his family moved to racially segregated Louisville. In high school, Reese was so small that he did not play baseball until senior year, at which time he weighed only 120 pounds and played just six games as a second baseman. He graduated from duPont Manual High School in 1937. He worked as a cable splicer for the Louisville phone company, only playing amateur baseball in a church league. When Reese's team reached the league championship, the minor league Louisville Colonels allowed them to play the championship game on their field. Reese impressed Colonels owner Cap Neal, who signed him to a contract for a $200 bonus.

The LA Dodgers Got Their Name From Brooklyn's Deadly Streetcars

Adam Clark Estes

6/10/15 6:05pm

Most people know that the blue-hatted Los Angeles Dodgers were once the Brooklyn Dodgers. But while you may have assumed that the “Dodgers” moniker referred to avoiding a tag or stealing a base, the true story is more complicated. That’s because the Brooklyn Dodgers were once the Brooklyn Trolley Dodgers—and those trolleys were deadly.

But before we get into the etymology of “Dem Bums” from Brooklyn, it’s useful to review a little bit of baseball history. It all started in the mid-19th century, when baseball was not yet a national pastime. It was a leisure activity and, initially, a way to build community and camaraderie in a country full of immigrants.

In many ways, New York City had become an epicenter of baseball fervor after the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York played the first full game against the New York Nine in 1845. (The New York Nine won 22-1.) The game’s popularity spread across the country, of course, but teams formed in other boroughs, including Brooklyn. In fact, the Atlantic Base Ball Club of Brooklyn won the very first national championship in 1857 and dominated the game for years to follow.

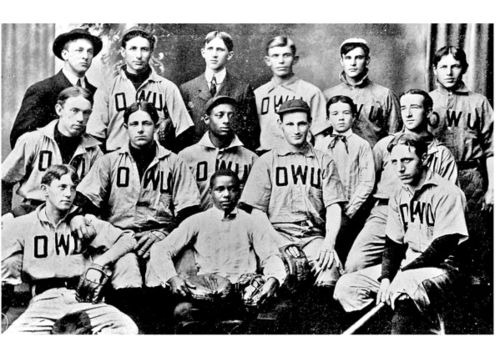

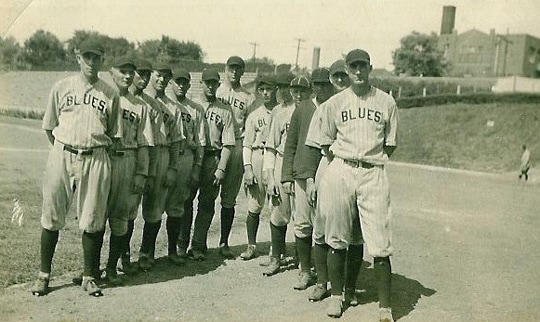

Here’s a fantastic photograph of the Brooklyn Atlantics, “champions of America,” in 1865:

Building on a tradition of success, real estate magnate Charles Byrne formed another baseball team in 1883: the Brooklyn Grays. At this point in baseball history, teams were largely known by their colors, and it was up to the newspaper writers to come up with their names. The Brooklyn Grays became the Brooklyn Bridegrooms in 1888, for instance, because six members of the team got married during the season. A few years later, however, another name started appearing in the press: the Brooklyn Trolley Dodgers.

There’s a bit of confusion surrounding the exact origins of the name “Trolley Dodgers.” As one sports history blog explains, the team moved in 1891 to Eastern Park which was surrounded by horse-drawn trolley lines. These slow-moving cars didn’t really require dodging, though. It wasn’t until the 1890s, when the Brooklyn Rapid Transit started to replace the rickety old trolleys. These fast-moving trolley cars were powered by a new-fangled thing called electricity.

This is where the story gets dark. In the late 19th-century, Americans weren’t accustomed to fast-moving vehicles running down city streets. Brooklyn was actually the second city in America to get an electric trolley line. As such, pedestrians hadn’t learned the habit of looking both ways when crossing the street. After all, if you stepped out in front of a horse, the horse would typically just stop in its tracks. An electric trolley car, however, would plow right over you.

Nevertheless, the speedier electric technology prevailed, and before long Brooklyn was completely covered in streetcar lines. The death toll from trolleys hitting pedestrians quickly rose. In the first year, 1892, five people died after being hit by trolleys. The Evening World reported that year:

[A] new precaution is necessary for the suffering Brooklynite. In addition to being always prepared to dodge the trolley wire, he must always be careful to step clear of the trolley rail.

There were 51 deaths in 1893 and 34 in 1894. By the time 1895 rolled around, Brooklyn had earned itself a reputation, and the newspaper writers across the country bestowed a new title on the city’s baseball team. The first use of the team name Trolley Dodgers actually popped up in print over a hundred miles away from Brooklyn. From The Scranton Tribune on May 11, 1865:

The “Rainmakers” and the “Trolley Dodgers” are the latest terms used by base ball writers to designate the Phillies and Brooklyns respectively.

The name stuck. Soon many newspapers were referring to Brooklyn’s baseball team as the Trolley Dodgers. One magazine called it a “playful descriptive term,” though some might think it somewhat derisive towards Brooklynites. Inevitably, however, the city—which became a borough of New York City in 1897—embraced the term.

Over time, the Trolley Dodger moniker was shortened to Dodgers. The baseball club officially acknowledged the nickname in 1933, when it put “Dodgers” on its jerseys. Five years later, the now familiar Dodgers script appeared. It’s the same script that Jackie Robinson wore when he became the first African-American player in the major leagues in 1947. In 1958, the Dodgers moved West, but the Los Angeles Dodgers kept the name, as well as the same iconic logo.

In the years that followed, trolley cars disappeared from the streets of Brooklyn and Los Angeles. But the legend lives on as a lasting memory of how technology and city culture collide, sometimes to a deadly degree.

Adam Clark Estes

6/10/15 6:05pm

Most people know that the blue-hatted Los Angeles Dodgers were once the Brooklyn Dodgers. But while you may have assumed that the “Dodgers” moniker referred to avoiding a tag or stealing a base, the true story is more complicated. That’s because the Brooklyn Dodgers were once the Brooklyn Trolley Dodgers—and those trolleys were deadly.

But before we get into the etymology of “Dem Bums” from Brooklyn, it’s useful to review a little bit of baseball history. It all started in the mid-19th century, when baseball was not yet a national pastime. It was a leisure activity and, initially, a way to build community and camaraderie in a country full of immigrants.

In many ways, New York City had become an epicenter of baseball fervor after the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York played the first full game against the New York Nine in 1845. (The New York Nine won 22-1.) The game’s popularity spread across the country, of course, but teams formed in other boroughs, including Brooklyn. In fact, the Atlantic Base Ball Club of Brooklyn won the very first national championship in 1857 and dominated the game for years to follow.

Here’s a fantastic photograph of the Brooklyn Atlantics, “champions of America,” in 1865:

Building on a tradition of success, real estate magnate Charles Byrne formed another baseball team in 1883: the Brooklyn Grays. At this point in baseball history, teams were largely known by their colors, and it was up to the newspaper writers to come up with their names. The Brooklyn Grays became the Brooklyn Bridegrooms in 1888, for instance, because six members of the team got married during the season. A few years later, however, another name started appearing in the press: the Brooklyn Trolley Dodgers.

There’s a bit of confusion surrounding the exact origins of the name “Trolley Dodgers.” As one sports history blog explains, the team moved in 1891 to Eastern Park which was surrounded by horse-drawn trolley lines. These slow-moving cars didn’t really require dodging, though. It wasn’t until the 1890s, when the Brooklyn Rapid Transit started to replace the rickety old trolleys. These fast-moving trolley cars were powered by a new-fangled thing called electricity.

This is where the story gets dark. In the late 19th-century, Americans weren’t accustomed to fast-moving vehicles running down city streets. Brooklyn was actually the second city in America to get an electric trolley line. As such, pedestrians hadn’t learned the habit of looking both ways when crossing the street. After all, if you stepped out in front of a horse, the horse would typically just stop in its tracks. An electric trolley car, however, would plow right over you.

Nevertheless, the speedier electric technology prevailed, and before long Brooklyn was completely covered in streetcar lines. The death toll from trolleys hitting pedestrians quickly rose. In the first year, 1892, five people died after being hit by trolleys. The Evening World reported that year:

[A] new precaution is necessary for the suffering Brooklynite. In addition to being always prepared to dodge the trolley wire, he must always be careful to step clear of the trolley rail.

There were 51 deaths in 1893 and 34 in 1894. By the time 1895 rolled around, Brooklyn had earned itself a reputation, and the newspaper writers across the country bestowed a new title on the city’s baseball team. The first use of the team name Trolley Dodgers actually popped up in print over a hundred miles away from Brooklyn. From The Scranton Tribune on May 11, 1865:

The “Rainmakers” and the “Trolley Dodgers” are the latest terms used by base ball writers to designate the Phillies and Brooklyns respectively.

The name stuck. Soon many newspapers were referring to Brooklyn’s baseball team as the Trolley Dodgers. One magazine called it a “playful descriptive term,” though some might think it somewhat derisive towards Brooklynites. Inevitably, however, the city—which became a borough of New York City in 1897—embraced the term.

Over time, the Trolley Dodger moniker was shortened to Dodgers. The baseball club officially acknowledged the nickname in 1933, when it put “Dodgers” on its jerseys. Five years later, the now familiar Dodgers script appeared. It’s the same script that Jackie Robinson wore when he became the first African-American player in the major leagues in 1947. In 1958, the Dodgers moved West, but the Los Angeles Dodgers kept the name, as well as the same iconic logo.

In the years that followed, trolley cars disappeared from the streets of Brooklyn and Los Angeles. But the legend lives on as a lasting memory of how technology and city culture collide, sometimes to a deadly degree.

Click to set custom HTML

Jackie Robinson

This article was written by Rick Swaine

Jackie Robinson is perhaps the most historically significant baseball player ever, ranking with Babe Ruth in terms of his impact on the national pastime. Ruth changed the way baseball was played; Jackie Robinson changed the way Americans thought. When Robinson took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947, more than sixty years of racial segregation in major-league baseball came to an end. He was the first acknowledged black player to perform in the Major Leagues in the twentieth century and went on to be the first to win a batting title, the first to win the Most Valuable Player award, and the first to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. He won major-league baseball's first official Rookie of the Year award and was the first baseball player, black or white, to be featured on a United States postage stamp.

The raw statistics only scratch the surface in evaluating Jackie Robinson as a ballplayer. Because of institutionalized racism and World War II, he did not play his first big-league game until he was twenty-eight years old, and therefore his major-league career spanned only ten seasons. His lifetime batting average was a solid .311, but because of the brevity of his career, his cumulative statistics are relatively unimpressive by Hall of Fame standards.

But in what would be considered his prime years, ages twenty-eight to thirty-four, Robinson hit .319 and averaged more than 110 runs scored per season. He drove in an average of eighty-five runs, and his average of nearly fifteen home runs per season was outstanding for a middle infielder of that era. And he averaged 24 stolen bases a season for a power-laden team that didn't need him to run very often.

Colorfully described as a tiger in the field and a lion at bat, the right-handed-hitting Robinson crowded the plate and dared opposing hurlers to dust him off—a challenge they frequently accepted. He was an excellent bunter, good at the sacrifice and always a threat to lay one down for a hit. Not known as a home-run hitter, he displayed line-drive power to all fields, had a good eye for the strike zone, and rarely struck out. For his entire big-league career, he drew 740 walks and struck out only 291 times—an extremely impressive ratio.

Second base was Robinson's best position. In a 1987 "Player's Choice" survey, he was voted the greatest second baseman of his era despite having played there regularly for only five seasons. Though not a smooth glove man in the classic sense, he was sure-handed and possessed good range and instincts. He made up for an average arm by standing his ground on double plays and getting rid of the ball quickly. Robinson also displayed his versatility by playing regularly at first base, at third base, and in left field when the needs of the team dictated it.

It was running the bases, however, where Robinson's star shined brightest. He was a dynamo on the basepaths—fast, clever, daring, and rough. He was the most dangerous base runner since Ty Cobb, embarrassing and intimidating the opposition into beating themselves with mental and physical errors. Former teammate and big-league manager Bobby Bragan, who initially objected to Jackie's presence on the Dodgers, called him the best he ever saw at getting called safe after being caught in rundown situations. He created havoc by taking impossibly long leads, jockeying back and forth, and threatening to steal on every pitch. His mere presence on base was enough to upset the most steely-nerved veteran hurlers.

Robinson revived the art of stealing home, successfully making it nineteen times in his career—tied with Frankie Frisch for the most since World War I. At the age of thirty-five in 1954, he became the first National Leaguer to steal his way around the bases in twenty-six years, and a year later he became one of only twelve men to steal home in the World Series.

Throughout his career, Jackie Robinson was a fearless competitor. As Leo Durocher, first his manager and later an archrival, so elegantly phrased it, "You want a guy that comes to play. But (Robinson) didn't just come to play. He came to beat you. He came to stuff the damn bat right up your ass."1

Jack Roosevelt Robinson was born on January 31, 1919, in Cairo, Georgia, a sleepy Southern town near the Florida border. Jackie was the youngest of five children, four boys and a girl, born to impoverished sharecroppers Jerry and Mallie Robinson. Jerry Robinson deserted the family six months after Jackie was born. Mallie Robinson, a strong, devoutly religious woman, moved the struggling family across the country by rail to Pasadena, California, in 1920 when Jackie was fourteen-months old. She worked as a domestic to support her family; leftovers from the kitchens of families she worked for often constituted their daily diet.

With the help of a welfare agency, the Robinson family purchased a home in a predominantly white Pasadena neighborhood, where neighbors immediately petitioned to get rid of the newcomers and even offered to buy them out. When those ploys failed the family was harassed for several years. The Robinson boys often had to fight to defend themselves, and young Jackie was involved in his share of scrapes with white youths and had some run-ins with authorities.

Jackie's athletic talent became evident at an early age. But he wasn't the only gifted athlete in the family. His older brother Mack became a world-class track star, finishing second in the 200-yard dash to Jesse Owens in the 1936 Olympics. But after Olympic stardom and college, the only job Mack Robinson could find was janitorial work for the City of Pasadena. It was a position he soon lost. As in most of the country at that time, Jim Crow rules prevailed in Pasadena. Black citizens were permitted to use the city's public swimming pool only one day a week. When a judge ordered full access to the pool for black citizens, the city fathers responded by firing black employees, including Mack Robinson.

After starring in baseball, football, basketball, and track at Muir Technical High School and Pasadena Junior College, Jackie declined many other offers to enroll at the University of California at Los Angeles, near his Pasadena home. Robinson gained national fame at UCLA in 1940 and 1941. He became the school's first four-letter man and was called the "Jim Thorpe of his race" for his multisport skills.2 Sharing rushing duties with Kenny Washington, who later became one of the first black men to play in the National Football League, Jackie averaged 11-plus yards per carry as a junior. Sports Weeklycalled him "the greatest ball carrier on the gridiron today."3 On the basketball court Jackie led the Pacific Coast Conference in scoring as a junior and as a senior.

Although he wasn't named to the first, second, or third all-conference teams, one coach called him "the best basketball player in the United States."4 Already the holder of the national junior college long-jump record, he captured the NCAA long-jump title and probably would have gone to the 1940 Olympics had they not been canceled by the war in Europe. In addition, he won swimming championships, reached the semifinals of the national Negro tennis tournament, and was the UCLA Bruins' regular shortstop. Baseball was probably Robinson's weakest sport at the university, although he'd been voted the most valuable player in Southern California junior college baseball.

Financial problems at home forced Robinson to drop out of college in his senior year a few credits short of graduation. He took a job as an athletic coach for the National Youth Administration and played semipro football for the Los Angeles Bulldogs. In the fall of 1941, he signed on to play professional football with the Honolulu Bears. Already a gate attraction and a hero in the black community, he got top billing as "the sensational all-American halfback."

Upon returning home from Hawaii shortly after Pearl Harbor, Robinson was drafted into the Army in 1942. Stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, he was originally denied entry into Officer Candidate School despite his college background. Intervention by a fellow soldier, boxing great Joe Louis, who was also stationed at the base, managed to get the decision reversed. Yet, Jackie was not allowed to play on the segregated camp baseball team, which infuriated him so much that he refused to play on the football team even when superior officers pressured him to do so. After OCS, Robinson was appointed morale officer for the black troops at Fort Riley and won concessions for them that predictably angered a few higher-ups in command.

Reassigned to Ford Hood, Texas, Jackie continued to be controversial. On July 6, 1944 he defied a white bus driver's orders to move to the back of the bus "where the coloreds belonged." When the base provost marshal and military police supported the driver, Robinson objected vehemently and was subject to court-martial. Facing a dishonorable discharge, Jackie prevailed at the hearing. But the Army had had enough of the controversial young black lieutenant and quickly mustered him out with an honorable discharge.

It's ironic that Jackie Robinson's difficulties with white authority in the military led directly to his rise to the top of Branch Rickey's list of candidates to break baseball's color barrier. Rickey, the orchestrator of Organized Baseball's desegregation, was the president, general manager, and a part-owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Rickey's scouts had been surreptitiously scouring the Negro Leagues for major-league talent for some time before tapping Robinson to break the unwritten, and diligently enforced, gentlemen's agreement that banned blacks from participating in Organized Baseball.

Rickey was looking for a black pioneer who—in addition to possessing the requisite talent—was educated, sober, and accustomed to competing with and against white athletes. Robinson met those conditions. He grew up in a racially mixed environment, attended school with white classmates, and matriculated at UCLA. He'd been an officer in the military. He was well-spoken, personable, and comfortable in front of crowds. He had experienced the glare of the spotlight and reveled in it. Also extremely important to the pious Rickey was the fact that Robinson was a nonsmoker and nondrinker. Nor was he a womanizer; he was planning to marry his college sweetheart, Rachel Annetta Isum. In addition, Jackie was a Methodist, as was Rickey, and he coincidentally shared a birthday with Branch Rickey Jr. Jackie and Rachel were married in Los Angeles on February 10, 1946.

Certainly there were other black ballplayers who possessed the qualifications Rickey sought. Monte Irvin and Larry Doby were two obvious candidates. But when Rickey sent his scouts to scour the nation for the best black player, Irvin and Doby were overseas, still in the armed forces. Robinson, though he was far from being considered the best player in Negro baseball, was available due to the early termination of his own military obligation.

After his discharge, Robinson had joined the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League for the 1945 season. The Monarchs, one of the most successful franchises in the Negro Leagues, had been ravaged by the manpower demands of the war, but their roster still included veteran stars Ted "Double Duty" Radcliffe, Hilton Smith, and Satchel Paige. Flashy-fielding veteran Jesse Williams moved over to second base to make room for Jackie at shortstop. Though Robinson hit well over .300 and showed speed and power as a rookie, he disliked the nomadic and often boisterous barnstorming life and was incensed by the Jim Crow laws that the Monarchs often encountered on the road.

On October 23, 1945, it was announced to the world that Robinson had signed a contract to play baseball for the Montreal Royals of the International League, the top minor-league team in the Dodgers organization. Robinson had actually signed a few months earlier. In that now-legendary meeting, Rickey extracted a promise that Jackie would hold his sharp tongue and quick fists in exchange for the opportunity to break Organized Baseball's color barrier.

The integration movement in general had picked up steam during World War II as black American soldiers fought and died beside whites. In fact, the decade leading up to Robinson's signing had been marked by significant progress in efforts to gain equal rights for minorities in all facets of life. Yet the moguls running Major League Baseball stubbornly resisted efforts to integrate the sport, refusing to consider black players even as the talent pool was depleted by the war and one-armed and one-legged players could be found among the old-timers, teenagers, and 4-Fs gracing big-league rosters.

But in November 1944, longtime Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who was generally thought to be against integration, died of a heart attack. Landis's passing was the break Branch Rickey needed to begin implementing his plan to integrate the Dodgers.

When Robinson's signing was announced, the news was heralded in black newspapers and generally received positive reviews in national publications despite objections and attacks from predictable quarters. But Rickey and the Dodgers faced near-unanimous disapproval from the Organized Baseball establishment. After the initial furor died down, a campaign to downplay Robinson's talent and the import of the event began. The New York Daily News rated Robinson's chances of making the grade as 1,000 to 1. An editorial in The Sporting News deemed Robinson a player of Class C ability and predicted, "The waters of competition in the International League will flood far over his head."5 Star pitcher Bob Feller of the Cleveland Indians said that Robinson had "football shoulders and couldn't hit an inside pitch to save his neck."6

Muscularly built with a thick neck and wide shoulders, Robinson did look more like a halfback than an infielder. He suffered from rickets as a child and walked with a pigeon-toed gait, but on the diamond he moved with amazing quickness. He stood five feet eleven and weighed 190 to 195 pounds in his prime, although he thickened noticeably in the latter stages of his career. In the decades prior to Robinson's entry into Organized Baseball, there were several major leaguers whose skin tone caused doubts about their racial background. There could be no doubt about ebony-skinned Jackie Robinson. Columnist John Crosby called him "the blackest black man, as well as one of the handsomest, I ever saw."7

Plagued by a sore arm during the Royals' 1946 spring training camp, Jackie performed poorly, generating numerous "I told you so" claims. But when Montreal opened the season on April 18, 1946, against the Jersey City Giants at Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City, Robinson was playing second base and hitting second in the batting order.

The first twentieth-century appearance by an acknowledged black player in Organized Baseball was a preview of things to come. In front of a packed house, Jackie lashed out four hits and scored four times to lead Montreal to a 14–1 victory. After grounding out in his first at-bat, he blasted a three-run homer over the left-field wall in the third inning. In the fifth inning he bunted for a hit, stole second, and made a daring play to take third on a grounder to the third baseman. From third base he danced far off the bag, darting back and forth and bluffing a steal until the harried pitcher balked him home. Two innings later, he singled sharply to right field and stole second base again before scoring on a triple. In the eighth Jackie again bunted safely. He once again took an extra base, advancing from first to third on an infield single, and again scored by provoking a balk by the Jersey City hurler.

The next day, the headline in the Pittsburgh Courier read: "Jackie Stole the Show."8 According to Joe Bostic of New York City's Amsterdam News, "He did everything but help the ushers seat the crowd."9

Baseball's defense for keeping the game segregated hinged primarily on two points. The first was the contention that there just weren't any black players good enough to merit a shot at the majors at the time. The second centered on financial concerns—the fear that white fans wouldn't pay to watch Negro players and didn't want to sit in the stands beside black fans. There was also much feigned concern about the financial impact on the established Negro Leagues.

But Jackie Robinson's first year in Organized Baseball emphatically dispelled those tired excuses. He was a sensation on the field, the Royals dominated the International League, and the turnstiles hummed. Thanks to Jackie, the Royals established a new attendance record in Montreal, and his impact on the road was even greater, as attendance at Royals games in other International League cities almost tripled over the previous year. More than a million people came to watch Robinson and the Royals perform that year, an amazing figure for the minor leagues at the time.

For the season Robinson led the International League with a .349 batting average and scored 113 runs in 124 games to pace the circuit in that department as well. His forty stolen bases were the second highest total in the league and he led the league's second basemen in fielding. Jackie led the Royals to the International League pennant, by a nineteen and a half game margin, and to victory in the Little World Series. After the Series, ecstatic fans wanted to hoist Jackie on their shoulders in celebration, but Jackie had a plane to catch. They chased him for three blocks, prompting a journalist to observe, "It was probably the only day in history that a black man ran from a white mob with love instead of hate on its mind."10

In preparation for the 1947 campaign the Brooklyn Dodgers and their top farm clubs set up spring training camp in Havana, Cuba. Based on his performance at Montreal it seemed a foregone conclusion that Robinson would get a chance with the parent team, but he was still listed on the Royals' roster when the workouts started. Rickey chose Havana to avoid the racial attitudes of the spring training sites in the South. His plan was to allow the Dodgers' veterans to gradually get used to having Jackie around and to see for themselves what an asset he would be to their pennant prospects. Three other black players, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, and Roy Partlow, were also on hand. Rickey scheduled a seven-game exhibition series between the Dodgers and the Royals to showcase Robinson's skills, and Jackie dominated the contests with a .625 batting average.

One problem that Rickey and Robinson had to overcome was that the Dodgers had Eddie Stanky playing second base. Therefore it was determined that Robinson would make his major-league debut at first base, a strange position for a man who had always been involved in the action in the middle of the diamond.

During training camp, a crisis arose when a core of Southerners on the team began to circulate a petition against Robinson. The dissenters were reportedly led by outfielder Dixie Walker, who initially dismissed the news of Robinson's signing with the comment, "As long as he isn't with the Dodgers, I'm not worried."11 Rickey and manager Leo Durocher promptly quashed the mini-rebellion. Shortly thereafter, Durocher, an avid Robinson supporter, received a one-year suspension from the commissioner's office for associating with gamblers and other “unsavory” characters. Rickey deftly took advantage of the cover provided by the resulting clamor to quietly transfer Robinson to the Brooklyn roster.

Contrary to dire predictions, Robinson's first season in the Major Leagues went fairly smoothly as the rookie steadfastly stuck by his promise to Rickey to turn the other cheek. Tension surrounding his first game was defused by a series of preseason exhibition contests against the Yankees in New York, and Jackie's Opening Day debut against the Braves was actually somewhat anticlimactic.

He received death threats when the club visited Cincinnati, but, in an oft-told but undocumented story, Dodgers shortstop Pee Wee Reese, a native son of Kentucky, draped an arm over the shoulders of the nervous rookie infielder in a courageous public show of support. Later, a threatened strike by the St. Louis Cardinals was short-circuited by a show of force by league president Ford Frick.

Jackie's worst experience came at the hands of the Philadelphia Phillies. Led by manager Ben Chapman, the Phils baited Robinson so cruelly that he later admitted, "It brought me nearer to cracking up than I had ever been."12 But the Chapman episode actually served to strengthen support for Robinson and even converted some of his detractors. Stanky, who originally had opposed playing with Robinson, challenged the Phillies to pick on someone who could fight back. Public reaction against Chapman was so severe that he had to ask Robinson to pose for a photo with him to save his job. Jackie graciously complied.

For his rookie campaign, Robinson hit .297, led the league with twenty-nine stolen bases, and finished second in the National League with 125 runs scored. In 151 games he lashed out 175 hits, including 12 home runs. Usually hitting second in the batting order, he walked seventy-four times and led the league in sacrifice hits. On defense, his sixteen errors at first base were the second highest total in the league, but his fielding was generally considered adequate.

With Robinson the biggest addition to the lineup, the Dodgers captured the National League pennant. In the World Series, Jackie and his teammates lost to the powerful Yankees in a thrilling seven-game classic. The 1947 season was the first in which the full membership of the Baseball Writers Association of America selected a Rookie of the Year, and Robinson beat out twenty-one-game-winner Larry Jansen of the New York Giants for the award. In the National League Most Valuable Player voting, he finished fifth. At season's end, Dixie Walker admitted that "(Robinson) is everything Branch Rickey said he was when he came up from Montreal."13

The integration of major-league baseball proceeded without critical incident. Though Robinson was scorned by some of his teammates, was harassed by enemy bench jockeys, and received a steady diet of fastballs close to his head; he faithfully abided by his promise to Rickey to turn the other cheek. Even when veteran outfielder Enos "Country" Slaughter of the Cardinals appeared to deliberately try to maim him with his spikes in an August 20 game at Ebbets Field, Jackie didn't retaliate.

In fact, baseball's "Great Experiment" was a huge success. Despite the concerns of the owners, integration proved to be a financial windfall for Major League Baseball. Robinson and the Dodgers eclipsed the home attendance record they had set the previous year. They also broke single-game attendance records in every National League ballpark they played in during the 1947 season, with the exception of Cincinnati's Crosley Field, where the attendance record for the first major-league night game held up. Near the end of the season, Jackie was feted by fans with a day in his honor. At year's end, he finished runner-up to crooner Bing Crosby in a national popularity poll.

Before the 1948 season, Eddie Stanky was swapped to the Boston Braves to open up the Dodgers' second-base slot for Robinson. Jackie reported to camp out of shape and got off to a poor start. He was shifted back to first base for thirty games while utilityman Eddie Miksis manned second for the Dodgers. Eventually, Gil Hodges emerged as the club's regular first baseman, and Robinson returned to second. He finished strong at the plate, ending the year with a .296 batting mark and leading the league's regular second basemen in fielding percentage. Spending more time in the power spots in the batting order, he drove in 85 runs, tops on the disappointing third-place squad.

In 1949, Robinson enjoyed the best season of his career, establishing career highs in games played, hits, batting average, slugging, runs batted in, and stolen bases as the Dodgers captured the National League pennant by a single game. He won the batting title with a .342 mark and his major-league-leading thirty-seven steals were the highest total in the National League in nineteen years. He finished second in the league in runs batted in (124), hits (203), and on-base percentage (.432), and third in slugging average (.528), runs scored (122), doubles (38), and triples (12). His efforts were rewarded with his selection as the National League Most Valuable Player.

Robinson enjoyed two more superb seasons in 1950 and 1951, batting .328 and .338 and finishing second and third respectively in the batting race. Both years the Dodgers lost the pennant on the last day of the season, although Jackie's heroics kept them in the hunt until the bitter end. In 1951, his spectacular play forced the playoff with the Giants that would be decided by Bobby Thomson's momentous home run. In the final regular-season contest against the Phillies, Robinson prevented the winning run from scoring in the ninth inning with a sensational diving catch, and blasted a game-winning homer in the fourteenth inning.

The Dodgers returned to the top of the National League standings in 1952 as Robinson hit .308, scored 104 runs, stole twenty-four bases, and belted nineteen homers. During the 1953 season, Jackie Robinson may have had his finest moment. He had worked hard to develop into a fine defensive second baseman. In 1951 he led National League second sackers in fielding and double plays, and had repeated as the double-play leader in 1952. But the Dodgers had a young black second baseman in their system, Jim Gilliam, who was ready for the big time.

Jackie graciously agreed to move to another position to make room for the rookie. The thirty-four-year-old veteran played seventy-six games in the outfield, and appeared fourty-four times at third base, nine times at second, and six times at first base during the 1953 campaign. He even filled in at shortstop in one game, the only time he played his original position as a major-leaguer. He hit .329, drove in ninety-five runs, and scored 109 times. Gilliam expertly filled the Dodgers' leadoff spot and was selected the National League Rookie of the Year.

The 1954 campaign was Robinson's last good season. Again shuttling between left field and third base, he batted .311, but age and accumulated injuries were starting to catch up with him. He stole only seven bases and missed thirty games.

In 1955, the year the Brooklyn Dodgers captured their first world championship, Robinson had the worst season statistically of his outstanding career. Sharing third base with light-hitting Don Hoak, he appeared in the field in fewer than 100 games and batted only .256. In the Dodgers' epic World Series victory, Robinson was at third base for six of the seven contests and though he hit poorly, he scored five times, including his shocking Game One steal of home.

Jackie rallied to hit .275 in 1956, his final season, while sharing third base with newly acquired Randy Jackson and occasionally filling in at second. Though a mere shadow of his former self, the thirty-seven-year-old veteran was still a force at the plate and on the basepaths. In the Dodgers' seven-game World Series loss to the Yankees, Jackie drew five walks, scored five times, and blasted a home run. He struck out in his last professional at-bat, but fittingly he went down fighting. Yankees catcher Yogi Berra had to throw him out at first base after dropping the third strike.

Jackie's last years with the Dodgers had not been harmonious. He disliked both manager Walt Alston and owner Walter O'Malley, whose power play forced Branch Rickey out of the Brooklyn front office in 1950. Though the Dodgers had captured the 1956 pennant, the once dominating nucleus was growing old. Robinson himself was no longer a top performer on the field and had become increasingly outspoken on racial issues both inside and outside of baseball. The Dodgers brass was hoping he'd step down gracefully, but Jackie refused to announce his retirement. Finally the club forced his hand by swapping him to the New York Giants on December 13, 1956, for journeyman hurler Dick Littlefield and $30,000 in cash.

On January 22, 1957 Robinson's retirement from baseball was announced in an exclusive article in Look magazine, in which he took a few parting shots at the remaining segregated teams in the majors. Jackie had actually decided to retire before he was dealt to the Giants, but couldn't say anything earlier because of his deal with Look. The Giants reportedly offered him $60,000 to stay, and the prospect of playing alongside Willie Mays definitely had some appeal. But when Brooklyn general manager Buzzy Bavasi publicly implied that Robinson was just trying to use the magazine article to get a better contract, he decided to prove the Dodgers wrong and declined the Giants' offer.

Though Robinson's career as a major-league baseball player was over, he wasn't about to retire from the spotlight. He joined the Chock full o'Nuts coffee company as a vice president and served as the chairman of the Board of Freedom National Bank, founded to provide loans and banking services for minority members who were largely being ignored by establishment banks. He authored several autobiographical works, wrote a weekly newspaper column, and hosted a radio show. Earlier he even tried his hand at acting, starring in the movie The Jackie Robinson Story.

Robinson remained an unofficial spokesman for African-Americans and a relentless crusader for civil rights. He became embroiled in politics. Though a strong supporter of Martin Luther King and the NAACP, he endorsed Richard Nixon over John F. Kennedy for president in 1960 because he felt Kennedy had not made it "his business to know colored people." Reportedly it was an action that he later came to regret.

In 1962 Robinson was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He was inducted along with former Cleveland pitching great Bob Feller, who had once predicted that Jackie's "football shoulders" would keep him from hitting big-league pitching. A few years after his retirement from baseball, Robinson acknowledged that he suffered from diabetes. His health declined under the ravages of the disease and at the age of fifty-three he suffered a fatal heart attack at his home in Stamford, Connecticut. He died on October 24, 1972, only months after his number 42 was officially retired by the Dodgers.

Although he always denied it, there's evidence that Robinson may have been the first insulin-dependent diabetic to play major-league baseball, despite his claim that it hadn't been diagnosed while he was an active player. But former tennis great Bill Talbert, a close friend of Robinson's and the first famous athlete known to perform with diabetes, believed that Jackie became insulin-dependent in midcareer. "I think Jackie felt it was a weakness. With all the publicity about blacks in baseball, he didn't want another thing to talk about," Talbert said after Robinson's death.14

More than two thousand people packed Riverside Church on Manhattan’s Upper West Side to hear the young Rev. Jesse Jackson deliver Jackie Robinson's eulogy. Tens of thousands lined the streets of Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant to watch the passage of his mile-long funeral procession.Robinson is buried in Cyprus Hill Cemetery in Brooklyn, along with his mother-in-law Zellee Isum and his son Jack Roosevelt, Jr. He was survived by his wife Rachel, son David and daughter Sharon.

Shortly after his death Robinson's ordeals and accomplishments were the subject of a Broadway musical, The First. In 1987, on the 40th anniversary of his breaking of color barrier, the Rookie of the Year Award was redesignated as the Jackie Robinson Award in honor of its first recipient. On the fiftieth anniversary of his debut, his number 42 was permanently retired by all major-league teams, although current major leaguers already wearing the number were allowed to keep it for the remainder of their careers.

Among the adjectives often used to describe Robinson's personal makeup are fearless, courageous, dynamic, defiant, and proud. But the most frequently used descriptor is probably aggressive. It's a word that defines his public life as a tireless campaigner against discrimination as well as his history making athletic career. Jackie, who was not known for self-deprecation, made the greatest understatement of his life in 1945 at the announcement of his signing. "Maybe I'm doing something for my race," he ventured.15

Former teammate Joe Black, speaking for generations of black ballplayers, later said, "When I look at my house. I say 'Thank God for Jackie Robinson.’”16

Note: This biography is an adaptation from The Black Stars Who Made Baseball Whole: The Jackie Robinson Generation in the Major Leagues by Rick Swaine (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2006).

Sources

Frommer, Harvey. Rickey & Robinson: The Men Who Broke Baseball's Color Barrier. New York: Macmillan, 1982.

Marshall, William. Baseball's Pivotal Era 1945-51. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999.

Moffi, Larry, and Jonathan Kronstadt. Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers 1947-1959. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1994.

Polner, Murray. Branch Rickey: A Biography. New York: Atheneum, 1982.

Robinson, Jackie, and Alfred Duckett. I Never Had It Made. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1972.

Rosenthal, Harold. The 10 Best Years of Baseball: An Informal History of the Fifties. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1979.

Shatzkin, Mike, and Jim Charlton. The Ballplayers: Baseball's Ultimate Biographical Reference. New York: Arbor House, William Morrow, 1990.

Tygiel, Jules. Baseball's Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy, New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

_____. Extra Bases: Reflections on Jackie Robinson, Race, & Baseball History. Lincoln: Univeristy of Nebraska Press, 2002.

_____. The Jackie Robinson Reader: Perspectives of an American Hero. New York: Penguin Books, 1997.

Wilber, Cynthia J. For the Love of the Game: Baseball Memories From the Men Who Were There. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1992.

Ardolino, Frank, "Jackie Robinson and the 1941 Honolulu Bears." The National Pastime, SABR, 1995.

Jacobs, Bruce, Baseball Stars of 1953. New York: Timely Comics, 1953.

Kirk, Al and Robert Bradley. "Jackie Robinson and the L.A. Red Devils." http://www.apbr.org/reddevils.html

Notes

1. Roger Kahn, The Boys of Summer, p. 358.

2. Vincent X Flaherty - Jackie Robinson Scrapbooks per Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment, p. 60.

3. Vincent X Flaherty - Jackie Robinson Scrapbooks per Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment, p. 60.

4. Unattributed - Jackie Robinson Scrapbooks per Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment, 1997, p.60.

5. Sporting News, November 1, 1945.

6. Pittsburgh Courier, November 3, 1945.

7. John Crosby, Syracuse Herald, November 12, 1972.

8. Pittsburgh Courier, April 27, 1946.

9. Joe Bostic, Amsterdam News, April 27, 1946.

10. Sam Maltin, Pittsburgh Courier, October 12, 1946.

11. Brooklyn Eagle, October 24, 1945.

12. Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made, p. 64

13. Golenbock, Bums.

14. Arnold Schechter, Sports Illustrated, April 22, 1985.

15. Sporting News, November 1, 1945.

16. New York Daily News, July 20, 1972.

This article was written by Rick Swaine

Jackie Robinson is perhaps the most historically significant baseball player ever, ranking with Babe Ruth in terms of his impact on the national pastime. Ruth changed the way baseball was played; Jackie Robinson changed the way Americans thought. When Robinson took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947, more than sixty years of racial segregation in major-league baseball came to an end. He was the first acknowledged black player to perform in the Major Leagues in the twentieth century and went on to be the first to win a batting title, the first to win the Most Valuable Player award, and the first to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. He won major-league baseball's first official Rookie of the Year award and was the first baseball player, black or white, to be featured on a United States postage stamp.

The raw statistics only scratch the surface in evaluating Jackie Robinson as a ballplayer. Because of institutionalized racism and World War II, he did not play his first big-league game until he was twenty-eight years old, and therefore his major-league career spanned only ten seasons. His lifetime batting average was a solid .311, but because of the brevity of his career, his cumulative statistics are relatively unimpressive by Hall of Fame standards.

But in what would be considered his prime years, ages twenty-eight to thirty-four, Robinson hit .319 and averaged more than 110 runs scored per season. He drove in an average of eighty-five runs, and his average of nearly fifteen home runs per season was outstanding for a middle infielder of that era. And he averaged 24 stolen bases a season for a power-laden team that didn't need him to run very often.

Colorfully described as a tiger in the field and a lion at bat, the right-handed-hitting Robinson crowded the plate and dared opposing hurlers to dust him off—a challenge they frequently accepted. He was an excellent bunter, good at the sacrifice and always a threat to lay one down for a hit. Not known as a home-run hitter, he displayed line-drive power to all fields, had a good eye for the strike zone, and rarely struck out. For his entire big-league career, he drew 740 walks and struck out only 291 times—an extremely impressive ratio.

Second base was Robinson's best position. In a 1987 "Player's Choice" survey, he was voted the greatest second baseman of his era despite having played there regularly for only five seasons. Though not a smooth glove man in the classic sense, he was sure-handed and possessed good range and instincts. He made up for an average arm by standing his ground on double plays and getting rid of the ball quickly. Robinson also displayed his versatility by playing regularly at first base, at third base, and in left field when the needs of the team dictated it.

It was running the bases, however, where Robinson's star shined brightest. He was a dynamo on the basepaths—fast, clever, daring, and rough. He was the most dangerous base runner since Ty Cobb, embarrassing and intimidating the opposition into beating themselves with mental and physical errors. Former teammate and big-league manager Bobby Bragan, who initially objected to Jackie's presence on the Dodgers, called him the best he ever saw at getting called safe after being caught in rundown situations. He created havoc by taking impossibly long leads, jockeying back and forth, and threatening to steal on every pitch. His mere presence on base was enough to upset the most steely-nerved veteran hurlers.

Robinson revived the art of stealing home, successfully making it nineteen times in his career—tied with Frankie Frisch for the most since World War I. At the age of thirty-five in 1954, he became the first National Leaguer to steal his way around the bases in twenty-six years, and a year later he became one of only twelve men to steal home in the World Series.

Throughout his career, Jackie Robinson was a fearless competitor. As Leo Durocher, first his manager and later an archrival, so elegantly phrased it, "You want a guy that comes to play. But (Robinson) didn't just come to play. He came to beat you. He came to stuff the damn bat right up your ass."1

Jack Roosevelt Robinson was born on January 31, 1919, in Cairo, Georgia, a sleepy Southern town near the Florida border. Jackie was the youngest of five children, four boys and a girl, born to impoverished sharecroppers Jerry and Mallie Robinson. Jerry Robinson deserted the family six months after Jackie was born. Mallie Robinson, a strong, devoutly religious woman, moved the struggling family across the country by rail to Pasadena, California, in 1920 when Jackie was fourteen-months old. She worked as a domestic to support her family; leftovers from the kitchens of families she worked for often constituted their daily diet.

With the help of a welfare agency, the Robinson family purchased a home in a predominantly white Pasadena neighborhood, where neighbors immediately petitioned to get rid of the newcomers and even offered to buy them out. When those ploys failed the family was harassed for several years. The Robinson boys often had to fight to defend themselves, and young Jackie was involved in his share of scrapes with white youths and had some run-ins with authorities.

Jackie's athletic talent became evident at an early age. But he wasn't the only gifted athlete in the family. His older brother Mack became a world-class track star, finishing second in the 200-yard dash to Jesse Owens in the 1936 Olympics. But after Olympic stardom and college, the only job Mack Robinson could find was janitorial work for the City of Pasadena. It was a position he soon lost. As in most of the country at that time, Jim Crow rules prevailed in Pasadena. Black citizens were permitted to use the city's public swimming pool only one day a week. When a judge ordered full access to the pool for black citizens, the city fathers responded by firing black employees, including Mack Robinson.

After starring in baseball, football, basketball, and track at Muir Technical High School and Pasadena Junior College, Jackie declined many other offers to enroll at the University of California at Los Angeles, near his Pasadena home. Robinson gained national fame at UCLA in 1940 and 1941. He became the school's first four-letter man and was called the "Jim Thorpe of his race" for his multisport skills.2 Sharing rushing duties with Kenny Washington, who later became one of the first black men to play in the National Football League, Jackie averaged 11-plus yards per carry as a junior. Sports Weeklycalled him "the greatest ball carrier on the gridiron today."3 On the basketball court Jackie led the Pacific Coast Conference in scoring as a junior and as a senior.

Although he wasn't named to the first, second, or third all-conference teams, one coach called him "the best basketball player in the United States."4 Already the holder of the national junior college long-jump record, he captured the NCAA long-jump title and probably would have gone to the 1940 Olympics had they not been canceled by the war in Europe. In addition, he won swimming championships, reached the semifinals of the national Negro tennis tournament, and was the UCLA Bruins' regular shortstop. Baseball was probably Robinson's weakest sport at the university, although he'd been voted the most valuable player in Southern California junior college baseball.

Financial problems at home forced Robinson to drop out of college in his senior year a few credits short of graduation. He took a job as an athletic coach for the National Youth Administration and played semipro football for the Los Angeles Bulldogs. In the fall of 1941, he signed on to play professional football with the Honolulu Bears. Already a gate attraction and a hero in the black community, he got top billing as "the sensational all-American halfback."

Upon returning home from Hawaii shortly after Pearl Harbor, Robinson was drafted into the Army in 1942. Stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, he was originally denied entry into Officer Candidate School despite his college background. Intervention by a fellow soldier, boxing great Joe Louis, who was also stationed at the base, managed to get the decision reversed. Yet, Jackie was not allowed to play on the segregated camp baseball team, which infuriated him so much that he refused to play on the football team even when superior officers pressured him to do so. After OCS, Robinson was appointed morale officer for the black troops at Fort Riley and won concessions for them that predictably angered a few higher-ups in command.

Reassigned to Ford Hood, Texas, Jackie continued to be controversial. On July 6, 1944 he defied a white bus driver's orders to move to the back of the bus "where the coloreds belonged." When the base provost marshal and military police supported the driver, Robinson objected vehemently and was subject to court-martial. Facing a dishonorable discharge, Jackie prevailed at the hearing. But the Army had had enough of the controversial young black lieutenant and quickly mustered him out with an honorable discharge.

It's ironic that Jackie Robinson's difficulties with white authority in the military led directly to his rise to the top of Branch Rickey's list of candidates to break baseball's color barrier. Rickey, the orchestrator of Organized Baseball's desegregation, was the president, general manager, and a part-owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Rickey's scouts had been surreptitiously scouring the Negro Leagues for major-league talent for some time before tapping Robinson to break the unwritten, and diligently enforced, gentlemen's agreement that banned blacks from participating in Organized Baseball.

Rickey was looking for a black pioneer who—in addition to possessing the requisite talent—was educated, sober, and accustomed to competing with and against white athletes. Robinson met those conditions. He grew up in a racially mixed environment, attended school with white classmates, and matriculated at UCLA. He'd been an officer in the military. He was well-spoken, personable, and comfortable in front of crowds. He had experienced the glare of the spotlight and reveled in it. Also extremely important to the pious Rickey was the fact that Robinson was a nonsmoker and nondrinker. Nor was he a womanizer; he was planning to marry his college sweetheart, Rachel Annetta Isum. In addition, Jackie was a Methodist, as was Rickey, and he coincidentally shared a birthday with Branch Rickey Jr. Jackie and Rachel were married in Los Angeles on February 10, 1946.

Certainly there were other black ballplayers who possessed the qualifications Rickey sought. Monte Irvin and Larry Doby were two obvious candidates. But when Rickey sent his scouts to scour the nation for the best black player, Irvin and Doby were overseas, still in the armed forces. Robinson, though he was far from being considered the best player in Negro baseball, was available due to the early termination of his own military obligation.

After his discharge, Robinson had joined the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League for the 1945 season. The Monarchs, one of the most successful franchises in the Negro Leagues, had been ravaged by the manpower demands of the war, but their roster still included veteran stars Ted "Double Duty" Radcliffe, Hilton Smith, and Satchel Paige. Flashy-fielding veteran Jesse Williams moved over to second base to make room for Jackie at shortstop. Though Robinson hit well over .300 and showed speed and power as a rookie, he disliked the nomadic and often boisterous barnstorming life and was incensed by the Jim Crow laws that the Monarchs often encountered on the road.

On October 23, 1945, it was announced to the world that Robinson had signed a contract to play baseball for the Montreal Royals of the International League, the top minor-league team in the Dodgers organization. Robinson had actually signed a few months earlier. In that now-legendary meeting, Rickey extracted a promise that Jackie would hold his sharp tongue and quick fists in exchange for the opportunity to break Organized Baseball's color barrier.

The integration movement in general had picked up steam during World War II as black American soldiers fought and died beside whites. In fact, the decade leading up to Robinson's signing had been marked by significant progress in efforts to gain equal rights for minorities in all facets of life. Yet the moguls running Major League Baseball stubbornly resisted efforts to integrate the sport, refusing to consider black players even as the talent pool was depleted by the war and one-armed and one-legged players could be found among the old-timers, teenagers, and 4-Fs gracing big-league rosters.

But in November 1944, longtime Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who was generally thought to be against integration, died of a heart attack. Landis's passing was the break Branch Rickey needed to begin implementing his plan to integrate the Dodgers.

When Robinson's signing was announced, the news was heralded in black newspapers and generally received positive reviews in national publications despite objections and attacks from predictable quarters. But Rickey and the Dodgers faced near-unanimous disapproval from the Organized Baseball establishment. After the initial furor died down, a campaign to downplay Robinson's talent and the import of the event began. The New York Daily News rated Robinson's chances of making the grade as 1,000 to 1. An editorial in The Sporting News deemed Robinson a player of Class C ability and predicted, "The waters of competition in the International League will flood far over his head."5 Star pitcher Bob Feller of the Cleveland Indians said that Robinson had "football shoulders and couldn't hit an inside pitch to save his neck."6

Muscularly built with a thick neck and wide shoulders, Robinson did look more like a halfback than an infielder. He suffered from rickets as a child and walked with a pigeon-toed gait, but on the diamond he moved with amazing quickness. He stood five feet eleven and weighed 190 to 195 pounds in his prime, although he thickened noticeably in the latter stages of his career. In the decades prior to Robinson's entry into Organized Baseball, there were several major leaguers whose skin tone caused doubts about their racial background. There could be no doubt about ebony-skinned Jackie Robinson. Columnist John Crosby called him "the blackest black man, as well as one of the handsomest, I ever saw."7

Plagued by a sore arm during the Royals' 1946 spring training camp, Jackie performed poorly, generating numerous "I told you so" claims. But when Montreal opened the season on April 18, 1946, against the Jersey City Giants at Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City, Robinson was playing second base and hitting second in the batting order.

The first twentieth-century appearance by an acknowledged black player in Organized Baseball was a preview of things to come. In front of a packed house, Jackie lashed out four hits and scored four times to lead Montreal to a 14–1 victory. After grounding out in his first at-bat, he blasted a three-run homer over the left-field wall in the third inning. In the fifth inning he bunted for a hit, stole second, and made a daring play to take third on a grounder to the third baseman. From third base he danced far off the bag, darting back and forth and bluffing a steal until the harried pitcher balked him home. Two innings later, he singled sharply to right field and stole second base again before scoring on a triple. In the eighth Jackie again bunted safely. He once again took an extra base, advancing from first to third on an infield single, and again scored by provoking a balk by the Jersey City hurler.

The next day, the headline in the Pittsburgh Courier read: "Jackie Stole the Show."8 According to Joe Bostic of New York City's Amsterdam News, "He did everything but help the ushers seat the crowd."9

Baseball's defense for keeping the game segregated hinged primarily on two points. The first was the contention that there just weren't any black players good enough to merit a shot at the majors at the time. The second centered on financial concerns—the fear that white fans wouldn't pay to watch Negro players and didn't want to sit in the stands beside black fans. There was also much feigned concern about the financial impact on the established Negro Leagues.

But Jackie Robinson's first year in Organized Baseball emphatically dispelled those tired excuses. He was a sensation on the field, the Royals dominated the International League, and the turnstiles hummed. Thanks to Jackie, the Royals established a new attendance record in Montreal, and his impact on the road was even greater, as attendance at Royals games in other International League cities almost tripled over the previous year. More than a million people came to watch Robinson and the Royals perform that year, an amazing figure for the minor leagues at the time.

For the season Robinson led the International League with a .349 batting average and scored 113 runs in 124 games to pace the circuit in that department as well. His forty stolen bases were the second highest total in the league and he led the league's second basemen in fielding. Jackie led the Royals to the International League pennant, by a nineteen and a half game margin, and to victory in the Little World Series. After the Series, ecstatic fans wanted to hoist Jackie on their shoulders in celebration, but Jackie had a plane to catch. They chased him for three blocks, prompting a journalist to observe, "It was probably the only day in history that a black man ran from a white mob with love instead of hate on its mind."10

In preparation for the 1947 campaign the Brooklyn Dodgers and their top farm clubs set up spring training camp in Havana, Cuba. Based on his performance at Montreal it seemed a foregone conclusion that Robinson would get a chance with the parent team, but he was still listed on the Royals' roster when the workouts started. Rickey chose Havana to avoid the racial attitudes of the spring training sites in the South. His plan was to allow the Dodgers' veterans to gradually get used to having Jackie around and to see for themselves what an asset he would be to their pennant prospects. Three other black players, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, and Roy Partlow, were also on hand. Rickey scheduled a seven-game exhibition series between the Dodgers and the Royals to showcase Robinson's skills, and Jackie dominated the contests with a .625 batting average.

One problem that Rickey and Robinson had to overcome was that the Dodgers had Eddie Stanky playing second base. Therefore it was determined that Robinson would make his major-league debut at first base, a strange position for a man who had always been involved in the action in the middle of the diamond.

During training camp, a crisis arose when a core of Southerners on the team began to circulate a petition against Robinson. The dissenters were reportedly led by outfielder Dixie Walker, who initially dismissed the news of Robinson's signing with the comment, "As long as he isn't with the Dodgers, I'm not worried."11 Rickey and manager Leo Durocher promptly quashed the mini-rebellion. Shortly thereafter, Durocher, an avid Robinson supporter, received a one-year suspension from the commissioner's office for associating with gamblers and other “unsavory” characters. Rickey deftly took advantage of the cover provided by the resulting clamor to quietly transfer Robinson to the Brooklyn roster.

Contrary to dire predictions, Robinson's first season in the Major Leagues went fairly smoothly as the rookie steadfastly stuck by his promise to Rickey to turn the other cheek. Tension surrounding his first game was defused by a series of preseason exhibition contests against the Yankees in New York, and Jackie's Opening Day debut against the Braves was actually somewhat anticlimactic.

He received death threats when the club visited Cincinnati, but, in an oft-told but undocumented story, Dodgers shortstop Pee Wee Reese, a native son of Kentucky, draped an arm over the shoulders of the nervous rookie infielder in a courageous public show of support. Later, a threatened strike by the St. Louis Cardinals was short-circuited by a show of force by league president Ford Frick.

Jackie's worst experience came at the hands of the Philadelphia Phillies. Led by manager Ben Chapman, the Phils baited Robinson so cruelly that he later admitted, "It brought me nearer to cracking up than I had ever been."12 But the Chapman episode actually served to strengthen support for Robinson and even converted some of his detractors. Stanky, who originally had opposed playing with Robinson, challenged the Phillies to pick on someone who could fight back. Public reaction against Chapman was so severe that he had to ask Robinson to pose for a photo with him to save his job. Jackie graciously complied.

For his rookie campaign, Robinson hit .297, led the league with twenty-nine stolen bases, and finished second in the National League with 125 runs scored. In 151 games he lashed out 175 hits, including 12 home runs. Usually hitting second in the batting order, he walked seventy-four times and led the league in sacrifice hits. On defense, his sixteen errors at first base were the second highest total in the league, but his fielding was generally considered adequate.

With Robinson the biggest addition to the lineup, the Dodgers captured the National League pennant. In the World Series, Jackie and his teammates lost to the powerful Yankees in a thrilling seven-game classic. The 1947 season was the first in which the full membership of the Baseball Writers Association of America selected a Rookie of the Year, and Robinson beat out twenty-one-game-winner Larry Jansen of the New York Giants for the award. In the National League Most Valuable Player voting, he finished fifth. At season's end, Dixie Walker admitted that "(Robinson) is everything Branch Rickey said he was when he came up from Montreal."13

The integration of major-league baseball proceeded without critical incident. Though Robinson was scorned by some of his teammates, was harassed by enemy bench jockeys, and received a steady diet of fastballs close to his head; he faithfully abided by his promise to Rickey to turn the other cheek. Even when veteran outfielder Enos "Country" Slaughter of the Cardinals appeared to deliberately try to maim him with his spikes in an August 20 game at Ebbets Field, Jackie didn't retaliate.

In fact, baseball's "Great Experiment" was a huge success. Despite the concerns of the owners, integration proved to be a financial windfall for Major League Baseball. Robinson and the Dodgers eclipsed the home attendance record they had set the previous year. They also broke single-game attendance records in every National League ballpark they played in during the 1947 season, with the exception of Cincinnati's Crosley Field, where the attendance record for the first major-league night game held up. Near the end of the season, Jackie was feted by fans with a day in his honor. At year's end, he finished runner-up to crooner Bing Crosby in a national popularity poll.

Before the 1948 season, Eddie Stanky was swapped to the Boston Braves to open up the Dodgers' second-base slot for Robinson. Jackie reported to camp out of shape and got off to a poor start. He was shifted back to first base for thirty games while utilityman Eddie Miksis manned second for the Dodgers. Eventually, Gil Hodges emerged as the club's regular first baseman, and Robinson returned to second. He finished strong at the plate, ending the year with a .296 batting mark and leading the league's regular second basemen in fielding percentage. Spending more time in the power spots in the batting order, he drove in 85 runs, tops on the disappointing third-place squad.

In 1949, Robinson enjoyed the best season of his career, establishing career highs in games played, hits, batting average, slugging, runs batted in, and stolen bases as the Dodgers captured the National League pennant by a single game. He won the batting title with a .342 mark and his major-league-leading thirty-seven steals were the highest total in the National League in nineteen years. He finished second in the league in runs batted in (124), hits (203), and on-base percentage (.432), and third in slugging average (.528), runs scored (122), doubles (38), and triples (12). His efforts were rewarded with his selection as the National League Most Valuable Player.

Robinson enjoyed two more superb seasons in 1950 and 1951, batting .328 and .338 and finishing second and third respectively in the batting race. Both years the Dodgers lost the pennant on the last day of the season, although Jackie's heroics kept them in the hunt until the bitter end. In 1951, his spectacular play forced the playoff with the Giants that would be decided by Bobby Thomson's momentous home run. In the final regular-season contest against the Phillies, Robinson prevented the winning run from scoring in the ninth inning with a sensational diving catch, and blasted a game-winning homer in the fourteenth inning.