T S Elliot

Those who only know T.S. Eliot from such early poems as “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” and The Waste Land may be surprised to encounter what many critics consider his greatest work, the Four Quartets. The Eliot of the earlier, better-known poems alternates between mocking dissection and tragic lamentation for the supposed cultural decay of the West; in The Waste Land especially, Eliot draws upon his considerable erudition to collapse centuries of poetic and religious text into shards of modernist ingenuity and sharp fragments of despairing irony. The Four Quartets, on the other hand—first published in 1943, though written separately over a period of six years—-attempts to unify traditions, in ways both more earnest and more oblique than readers of Eliot had seen before.

The central theme tying together the four poems—“Burnt Norton,” “East Coker,” “The Dry Salvages,” and “Little Gidding”—is time: as eternity, as emptiness, as a wasteland of words and gestures without meaning or purpose. “If all time is eternally present / All time is unredeemable,” the poet argues in “Burnt Norton,” and he goes on to illustrate ideas drawn from St. Augustine, the Christian mystics, and the Upanishads. Although, as George Orwell wrote in a review, the poems “appear on the surface to be about… certain localities in England and America with which Mr. Eliot has ancestral connexions,” they also serve as a philosophical apologia for his deepening Anglo-Catholicism. Orwell, however, doubted Eliot’s religious sincerity; “there is faith” in the poems, he wrote, “but not much hope, and certainly no enthusiasm.”

Yet much of the appeal of the Four Quartets to those of a mystical bent comes from the poems’ enacting of a meditative faith, however tenuous, held amidst tumults of meaningless activity and a chilling sense of cultural enervation. (One pregnant phrase from “Burnt Norton” inspired the title of a book on Zen and Christian mysticism.) Eliot’s conservatism may prevent him from imagining any sort of worldly human progress, but generations of readers have seen in the Four Quartets the profoundest meditation on a spiritual journey, and it is perhaps in those late poems, written in the poet’s middle age, that Eliot comes closest to his personal literary hero, Dante, who entered the dark wood in the Canto I of The Inferno while “halfway along life’s path.”

In a previous post on the Four Quartets, we featured Eliot himself reading the poems, and Mike Springer offered some helpful context on their settings. Above, we have the rare treat of a reading by Sir Alec Guinness. Recorded in 1971—six years before Guinness donned Obi-Wan Kenobi’s robes—we hear in his reading the gravitas that made his Star Wars Jedi guru seem so wise and weary (though apparently he did not relish that role). As an added bonus, below, hear an audio production of The Waste Land with clips of readings by Guinness, Ted Hughes, Fiona Shaw, Eliot himself, and more.

The central theme tying together the four poems—“Burnt Norton,” “East Coker,” “The Dry Salvages,” and “Little Gidding”—is time: as eternity, as emptiness, as a wasteland of words and gestures without meaning or purpose. “If all time is eternally present / All time is unredeemable,” the poet argues in “Burnt Norton,” and he goes on to illustrate ideas drawn from St. Augustine, the Christian mystics, and the Upanishads. Although, as George Orwell wrote in a review, the poems “appear on the surface to be about… certain localities in England and America with which Mr. Eliot has ancestral connexions,” they also serve as a philosophical apologia for his deepening Anglo-Catholicism. Orwell, however, doubted Eliot’s religious sincerity; “there is faith” in the poems, he wrote, “but not much hope, and certainly no enthusiasm.”

Yet much of the appeal of the Four Quartets to those of a mystical bent comes from the poems’ enacting of a meditative faith, however tenuous, held amidst tumults of meaningless activity and a chilling sense of cultural enervation. (One pregnant phrase from “Burnt Norton” inspired the title of a book on Zen and Christian mysticism.) Eliot’s conservatism may prevent him from imagining any sort of worldly human progress, but generations of readers have seen in the Four Quartets the profoundest meditation on a spiritual journey, and it is perhaps in those late poems, written in the poet’s middle age, that Eliot comes closest to his personal literary hero, Dante, who entered the dark wood in the Canto I of The Inferno while “halfway along life’s path.”

In a previous post on the Four Quartets, we featured Eliot himself reading the poems, and Mike Springer offered some helpful context on their settings. Above, we have the rare treat of a reading by Sir Alec Guinness. Recorded in 1971—six years before Guinness donned Obi-Wan Kenobi’s robes—we hear in his reading the gravitas that made his Star Wars Jedi guru seem so wise and weary (though apparently he did not relish that role). As an added bonus, below, hear an audio production of The Waste Land with clips of readings by Guinness, Ted Hughes, Fiona Shaw, Eliot himself, and more.

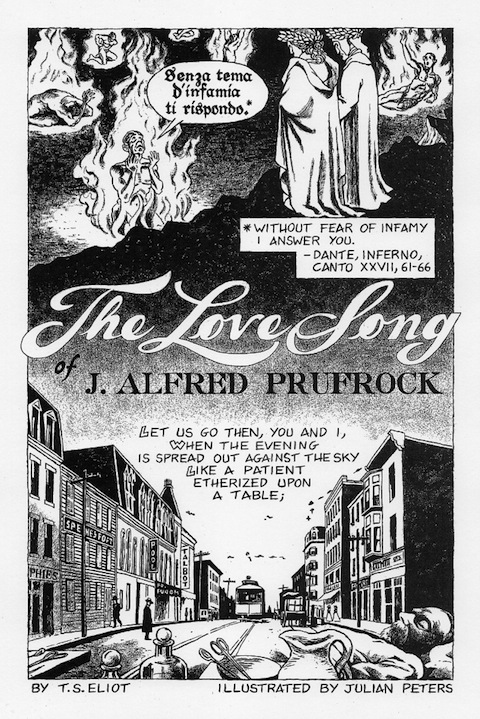

Poetry is as close as written language comes to the visual arts but, aside from narrative poems, it is not a medium easily adapted to visual forms. Perhaps some of the least adaptable, I would think, are the high modernists, whose obsessive focus on technique renders much of their work opaque to all but the most careful readers. The major poems of T.S. Eliot perhaps best represent this tendency. And yet comic artist Julian Peters is up to the challenge. Peters, who has previously adapted Poe, Keats, and Rimbaud, now takes on Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” and you can see the first nine pages at his site.

Written in 1910 and published five years later, “Prufrock” has become a standard reference for Eliot’s doctrine of the “objective correlative,” a concept he defines in his critical essay, “Hamlet and His Problems,” as “a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion.” It’s a theory he elaborates in “Tradition and the Individual Talent“ in his discussion of Dante. And Dante is where “Prufrock” begins, with an epigraph from the Inferno. Peters’ first page illustrates the agonized speaker of Dante’s lines, Guido da Montefeltro, a soul confined to the eight circle, whom you can see at the top of the title page shown above. Peters’ visual choices place us firmly in the hellish emotional realm of “Prufrock,” a seeming catalogue of the mundane that harbors a darker import. Peters gives us no hint of when we might expect new pages, but I for one am eager to see more.

Written in 1910 and published five years later, “Prufrock” has become a standard reference for Eliot’s doctrine of the “objective correlative,” a concept he defines in his critical essay, “Hamlet and His Problems,” as “a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion.” It’s a theory he elaborates in “Tradition and the Individual Talent“ in his discussion of Dante. And Dante is where “Prufrock” begins, with an epigraph from the Inferno. Peters’ first page illustrates the agonized speaker of Dante’s lines, Guido da Montefeltro, a soul confined to the eight circle, whom you can see at the top of the title page shown above. Peters’ visual choices place us firmly in the hellish emotional realm of “Prufrock,” a seeming catalogue of the mundane that harbors a darker import. Peters gives us no hint of when we might expect new pages, but I for one am eager to see more.

“20 Rules For Writing Detective Stories” By S.S. Van Dine, One of T.S. Eliot’s Favorite Genre Authors (1928) in Literature, Writing | February 5th, 2016

Every generation, it seems, has its preferred bestselling genre fiction. We’ve had fantasy and, at least in very recent history, vampire romance keeping us reading. The fifties and sixties had their westerns and sci-fi. And in the forties, it won’t surprise you to hear, detective fiction was all the rage. So much so that—like many an irritable contrarian critic today—esteemed literary tastemaker Edmund Wilson penned a cranky New Yorker piece in 1944 declaiming its popularity, writing “at the age of twelve… I was outgrowing that form of literature”; the form, that is, perfected by Edgar Allan Poe, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Wilkie Collins, and imitated by a host of pulp writers in Wilson’s day. Detective stories, in fact, were in vogue for the first few decades of the 20th century—since the appearance of Sherlock Holmes and a derivative 1907 character called “the Thinking Machine,” responsible, it seems, for Wilson’s loss of interest.

Thus, when Wilson learned that “of all people,”Paul Grimstad writes, T.S. Eliot “was a devoted fan of the genre,” he must have been particularly dismayed, as he considered Eliot “an unimpeachable authority in matters of literary judgment.” Eliot’s tastes were much more ecumenical than most critics supposed, his “attitude toward popular art forms… more capacious and ambivalent than he’s often given credit for.” The rhythms of ragtime pervade his early poetry, and “in his later years he wanted nothing more than to have a hit on Broadway.” (He succeeded, sixteen years after his death.) Eliot peppered his conversation and poetry with quotations from Arthur Conan Doyle and wrote several glowing reviews of detective novels by writers like Dorothy Sayers and Agatha Christie during the genre’s “Golden Age,” publishing them anonymously in his literary journal The Criterion in 1927.

One novel that impressed him above all others is titled The Benson Murder Case by an American writer named S.S. Van Dine, pen name of an art critic and editor named Willard Huntington Wright. Referring to an eminent art historian—whose tastes guided those of the wealthy industrial class—Eliot wrote that Van Dine used “methods similar to those which Bernard Berenson applies to paintings.” He had good reason to ascribe to Van Dine a curatorial sensibility. After a nervous breakdown, the writer “spent two years in bed reading more than two thousand detective stories, during with time he methodically distilled the genre’s formulas and began writing novels.” The year after Eliot’s appreciative review, Van Dine published his own set of criteria for detective fiction in a 1928 issue of The American Magazine. You can read his “Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories” below. They include such proscriptions as “There must be no love interest” and “The detective himself, or one of the official investigators, should never turn out to be the culprit.”

Rules, of course, are made to be broken (just ask G.K. Chesterton), provided one is clever and experienced enough to circumvent or disregard them. But the novice detective or mystery writer could certainly do worse than take the advice below from one of T.S. Eliot’s favorite detective writers. We’d also urge you to see Raymond Chandler’s 10 Commandments for Writing Detective Fiction.

THE DETECTIVE story is a kind of intellectual game. It is more — it is a sporting event. And for the writing of detective stories there are very definite laws — unwritten, perhaps, but none the less binding; and every respectable and self-respecting concocter of literary mysteries lives up to them. Herewith, then, is a sort Credo, based partly on the practice of all the great writers of detective stories, and partly on the promptings of the honest author’s inner conscience. To wit:

1. The reader must have equal opportunity with the detective for solving the mystery. All clues must be plainly stated and described.

2. No willful tricks or deceptions may be placed on the reader other than those played legitimately by the criminal on the detective himself.

3. There must be no love interest. The business in hand is to bring a criminal to the bar of justice, not to bring a lovelorn couple to the hymeneal altar.

4. The detective himself, or one of the official investigators, should never turn out to be the culprit. This is bald trickery, on a par with offering some one a bright penny for a five-dollar gold piece. It’s false pretenses.

5. The culprit must be determined by logical deductions — not by accident or coincidence or unmotivated confession. To solve a criminal problem in this latter fashion is like sending the reader on a deliberate wild-goose chase, and then telling him, after he has failed, that you had the object of his search up your sleeve all the time. Such an author is no better than a practical joker.

6. The detective novel must have a detective in it; and a detective is not a detective unless he detects. His function is to gather clues that will eventually lead to the person who did the dirty work in the first chapter; and if the detective does not reach his conclusions through an analysis of those clues, he has no more solved his problem than the schoolboy who gets his answer out of the back of the arithmetic.

7. There simply must be a corpse in a detective novel, and the deader the corpse the better. No lesser crime than murder will suffice. Three hundred pages is far too much pother for a crime other than murder. After all, the reader’s trouble and expenditure of energy must be rewarded.

8. The problem of the crime must he solved by strictly naturalistic means. Such methods for learning the truth as slate-writing, ouija-boards, mind-reading, spiritualistic se’ances, crystal-gazing, and the like, are taboo. A reader has a chance when matching his wits with a rationalistic detective, but if he must compete with the world of spirits and go chasing about the fourth dimension of metaphysics, he is defeated ab initio.

9. There must be but one detective — that is, but one protagonist of deduction — one deus ex machina. To bring the minds of three or four, or sometimes a gang of detectives to bear on a problem, is not only to disperse the interest and break the direct thread of logic, but to take an unfair advantage of the reader. If there is more than one detective the reader doesn’t know who his codeductor is. It’s like making the reader run a race with a relay team.

10. The culprit must turn out to be a person who has played a more or less prominent part in the story — that is, a person with whom the reader is familiar and in whom he takes an interest.

11. A servant must not be chosen by the author as the culprit. This is begging a noble question. It is a too easy solution. The culprit must be a decidedly worth-while person — one that wouldn’t ordinarily come under suspicion.

12. There must be but one culprit, no matter how many murders are committed. The culprit may, of course, have a minor helper or co-plotter; but the entire onus must rest on one pair of shoulders: the entire indignation of the reader must be permitted to concentrate on a single black nature.

13. Secret societies, camorras, mafias, et al., have no place in a detective story. A fascinating and truly beautiful murder is irremediably spoiled by any such wholesale culpability. To be sure, the murderer in a detective novel should be given a sporting chance; but it is going too far to grant him a secret society to fall back on. No high-class, self-respecting murderer would want such odds.

14. The method of murder, and the means of detecting it, must be be rational and scientific. That is to say, pseudo-science and purely imaginative and speculative devices are not to be tolerated in the roman policier. Once an author soars into the realm of fantasy, in the Jules Verne manner, he is outside the bounds of detective fiction, cavorting in the uncharted reaches of adventure.

15. The truth of the problem must at all times be apparent — provided the reader is shrewd enough to see it. By this I mean that if the reader, after learning the explanation for the crime, should reread the book, he would see that the solution had, in a sense, been staring him in the face-that all the clues really pointed to the culprit — and that, if he had been as clever as the detective, he could have solved the mystery himself without going on to the final chapter. That the clever reader does often thus solve the problem goes without saying.

16. A detective novel should contain no long descriptive passages, no literary dallying with side-issues, no subtly worked-out character analyses, no “atmospheric” preoccupations. such matters have no vital place in a record of crime and deduction. They hold up the action and introduce issues irrelevant to the main purpose, which is to state a problem, analyze it, and bring it to a successful conclusion. To be sure, there must be a sufficient descriptiveness and character delineation to give the novel verisimilitude.

17. A professional criminal must never be shouldered with the guilt of a crime in a detective story. Crimes by housebreakers and bandits are the province of the police departments — not of authors and brilliant amateur detectives. A really fascinating crime is one committed by a pillar of a church, or a spinster noted for her charities.

18. A crime in a detective story must never turn out to be an accident or a suicide. To end an odyssey of sleuthing with such an anti-climax is to hoodwink the trusting and kind-hearted reader.

19. The motives for all crimes in detective stories should be personal. International plottings and war politics belong in a different category of fiction — in secret-service tales, for instance. But a murder story must be kept gemütlich, so to speak. It must reflect the reader’s everyday experiences, and give him a certain outlet for his own repressed desires and emotions.

20. And (to give my Credo an even score of items) I herewith list a few of the devices which no self-respecting detective story writer will now avail himself of. They have been employed too often, and are familiar to all true lovers of literary crime. To use them is a confession of the author’s ineptitude and lack of originality. (a) Determining the identity of the culprit by comparing the butt of a cigarette left at the scene of the crime with the brand smoked by a suspect. (b) The bogus spiritualistic se’ance to frighten the culprit into giving himself away. (c) Forged fingerprints. (d) The dummy-figure alibi. (e) The dog that does not bark and thereby reveals the fact that the intruder is familiar. (f)The final pinning of the crime on a twin, or a relative who looks exactly like the suspected, but innocent, person. (g) The hypodermic syringe and the knockout drops. (h) The commission of the murder in a locked room after the police have actually broken in. (i) The word association test for guilt. (j) The cipher, or code letter, which is eventually unraveled by the sleuth.

Every generation, it seems, has its preferred bestselling genre fiction. We’ve had fantasy and, at least in very recent history, vampire romance keeping us reading. The fifties and sixties had their westerns and sci-fi. And in the forties, it won’t surprise you to hear, detective fiction was all the rage. So much so that—like many an irritable contrarian critic today—esteemed literary tastemaker Edmund Wilson penned a cranky New Yorker piece in 1944 declaiming its popularity, writing “at the age of twelve… I was outgrowing that form of literature”; the form, that is, perfected by Edgar Allan Poe, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Wilkie Collins, and imitated by a host of pulp writers in Wilson’s day. Detective stories, in fact, were in vogue for the first few decades of the 20th century—since the appearance of Sherlock Holmes and a derivative 1907 character called “the Thinking Machine,” responsible, it seems, for Wilson’s loss of interest.

Thus, when Wilson learned that “of all people,”Paul Grimstad writes, T.S. Eliot “was a devoted fan of the genre,” he must have been particularly dismayed, as he considered Eliot “an unimpeachable authority in matters of literary judgment.” Eliot’s tastes were much more ecumenical than most critics supposed, his “attitude toward popular art forms… more capacious and ambivalent than he’s often given credit for.” The rhythms of ragtime pervade his early poetry, and “in his later years he wanted nothing more than to have a hit on Broadway.” (He succeeded, sixteen years after his death.) Eliot peppered his conversation and poetry with quotations from Arthur Conan Doyle and wrote several glowing reviews of detective novels by writers like Dorothy Sayers and Agatha Christie during the genre’s “Golden Age,” publishing them anonymously in his literary journal The Criterion in 1927.

One novel that impressed him above all others is titled The Benson Murder Case by an American writer named S.S. Van Dine, pen name of an art critic and editor named Willard Huntington Wright. Referring to an eminent art historian—whose tastes guided those of the wealthy industrial class—Eliot wrote that Van Dine used “methods similar to those which Bernard Berenson applies to paintings.” He had good reason to ascribe to Van Dine a curatorial sensibility. After a nervous breakdown, the writer “spent two years in bed reading more than two thousand detective stories, during with time he methodically distilled the genre’s formulas and began writing novels.” The year after Eliot’s appreciative review, Van Dine published his own set of criteria for detective fiction in a 1928 issue of The American Magazine. You can read his “Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories” below. They include such proscriptions as “There must be no love interest” and “The detective himself, or one of the official investigators, should never turn out to be the culprit.”

Rules, of course, are made to be broken (just ask G.K. Chesterton), provided one is clever and experienced enough to circumvent or disregard them. But the novice detective or mystery writer could certainly do worse than take the advice below from one of T.S. Eliot’s favorite detective writers. We’d also urge you to see Raymond Chandler’s 10 Commandments for Writing Detective Fiction.

THE DETECTIVE story is a kind of intellectual game. It is more — it is a sporting event. And for the writing of detective stories there are very definite laws — unwritten, perhaps, but none the less binding; and every respectable and self-respecting concocter of literary mysteries lives up to them. Herewith, then, is a sort Credo, based partly on the practice of all the great writers of detective stories, and partly on the promptings of the honest author’s inner conscience. To wit:

1. The reader must have equal opportunity with the detective for solving the mystery. All clues must be plainly stated and described.

2. No willful tricks or deceptions may be placed on the reader other than those played legitimately by the criminal on the detective himself.

3. There must be no love interest. The business in hand is to bring a criminal to the bar of justice, not to bring a lovelorn couple to the hymeneal altar.

4. The detective himself, or one of the official investigators, should never turn out to be the culprit. This is bald trickery, on a par with offering some one a bright penny for a five-dollar gold piece. It’s false pretenses.

5. The culprit must be determined by logical deductions — not by accident or coincidence or unmotivated confession. To solve a criminal problem in this latter fashion is like sending the reader on a deliberate wild-goose chase, and then telling him, after he has failed, that you had the object of his search up your sleeve all the time. Such an author is no better than a practical joker.

6. The detective novel must have a detective in it; and a detective is not a detective unless he detects. His function is to gather clues that will eventually lead to the person who did the dirty work in the first chapter; and if the detective does not reach his conclusions through an analysis of those clues, he has no more solved his problem than the schoolboy who gets his answer out of the back of the arithmetic.

7. There simply must be a corpse in a detective novel, and the deader the corpse the better. No lesser crime than murder will suffice. Three hundred pages is far too much pother for a crime other than murder. After all, the reader’s trouble and expenditure of energy must be rewarded.

8. The problem of the crime must he solved by strictly naturalistic means. Such methods for learning the truth as slate-writing, ouija-boards, mind-reading, spiritualistic se’ances, crystal-gazing, and the like, are taboo. A reader has a chance when matching his wits with a rationalistic detective, but if he must compete with the world of spirits and go chasing about the fourth dimension of metaphysics, he is defeated ab initio.

9. There must be but one detective — that is, but one protagonist of deduction — one deus ex machina. To bring the minds of three or four, or sometimes a gang of detectives to bear on a problem, is not only to disperse the interest and break the direct thread of logic, but to take an unfair advantage of the reader. If there is more than one detective the reader doesn’t know who his codeductor is. It’s like making the reader run a race with a relay team.

10. The culprit must turn out to be a person who has played a more or less prominent part in the story — that is, a person with whom the reader is familiar and in whom he takes an interest.

11. A servant must not be chosen by the author as the culprit. This is begging a noble question. It is a too easy solution. The culprit must be a decidedly worth-while person — one that wouldn’t ordinarily come under suspicion.

12. There must be but one culprit, no matter how many murders are committed. The culprit may, of course, have a minor helper or co-plotter; but the entire onus must rest on one pair of shoulders: the entire indignation of the reader must be permitted to concentrate on a single black nature.

13. Secret societies, camorras, mafias, et al., have no place in a detective story. A fascinating and truly beautiful murder is irremediably spoiled by any such wholesale culpability. To be sure, the murderer in a detective novel should be given a sporting chance; but it is going too far to grant him a secret society to fall back on. No high-class, self-respecting murderer would want such odds.

14. The method of murder, and the means of detecting it, must be be rational and scientific. That is to say, pseudo-science and purely imaginative and speculative devices are not to be tolerated in the roman policier. Once an author soars into the realm of fantasy, in the Jules Verne manner, he is outside the bounds of detective fiction, cavorting in the uncharted reaches of adventure.

15. The truth of the problem must at all times be apparent — provided the reader is shrewd enough to see it. By this I mean that if the reader, after learning the explanation for the crime, should reread the book, he would see that the solution had, in a sense, been staring him in the face-that all the clues really pointed to the culprit — and that, if he had been as clever as the detective, he could have solved the mystery himself without going on to the final chapter. That the clever reader does often thus solve the problem goes without saying.

16. A detective novel should contain no long descriptive passages, no literary dallying with side-issues, no subtly worked-out character analyses, no “atmospheric” preoccupations. such matters have no vital place in a record of crime and deduction. They hold up the action and introduce issues irrelevant to the main purpose, which is to state a problem, analyze it, and bring it to a successful conclusion. To be sure, there must be a sufficient descriptiveness and character delineation to give the novel verisimilitude.

17. A professional criminal must never be shouldered with the guilt of a crime in a detective story. Crimes by housebreakers and bandits are the province of the police departments — not of authors and brilliant amateur detectives. A really fascinating crime is one committed by a pillar of a church, or a spinster noted for her charities.

18. A crime in a detective story must never turn out to be an accident or a suicide. To end an odyssey of sleuthing with such an anti-climax is to hoodwink the trusting and kind-hearted reader.

19. The motives for all crimes in detective stories should be personal. International plottings and war politics belong in a different category of fiction — in secret-service tales, for instance. But a murder story must be kept gemütlich, so to speak. It must reflect the reader’s everyday experiences, and give him a certain outlet for his own repressed desires and emotions.

20. And (to give my Credo an even score of items) I herewith list a few of the devices which no self-respecting detective story writer will now avail himself of. They have been employed too often, and are familiar to all true lovers of literary crime. To use them is a confession of the author’s ineptitude and lack of originality. (a) Determining the identity of the culprit by comparing the butt of a cigarette left at the scene of the crime with the brand smoked by a suspect. (b) The bogus spiritualistic se’ance to frighten the culprit into giving himself away. (c) Forged fingerprints. (d) The dummy-figure alibi. (e) The dog that does not bark and thereby reveals the fact that the intruder is familiar. (f)The final pinning of the crime on a twin, or a relative who looks exactly like the suspected, but innocent, person. (g) The hypodermic syringe and the knockout drops. (h) The commission of the murder in a locked room after the police have actually broken in. (i) The word association test for guilt. (j) The cipher, or code letter, which is eventually unraveled by the sleuth.

Click to set custom HTML

The Waste LandRelated Poem Content Details

BY T. S. ELIOT

FOR EZRA POUND

IL MIGLIOR FABBRO

I. The Burial of the Dead

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

Summer surprised us, coming over the Starnbergersee

With a shower of rain; we stopped in the colonnade,

And went on in sunlight, into the Hofgarten,

And drank coffee, and talked for an hour.

Bin gar keine Russin, stamm’ aus Litauen, echt deutsch.

And when we were children, staying at the arch-duke’s,

My cousin’s, he took me out on a sled,

And I was frightened. He said, Marie,

Marie, hold on tight. And down we went.

In the mountains, there you feel free.

I read, much of the night, and go south in the winter.

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,

And the dry stone no sound of water. Only

There is shadow under this red rock,

(Come in under the shadow of this red rock),

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

Frisch weht der Wind

Der Heimat zu

Mein Irisch Kind,

Wo weilest du?

“You gave me hyacinths first a year ago;

“They called me the hyacinth girl.”

—Yet when we came back, late, from the Hyacinth garden,

Your arms full, and your hair wet, I could not

Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither

Living nor dead, and I knew nothing,

Looking into the heart of light, the silence.

Oed’ und leer das Meer.

Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante,

Had a bad cold, nevertheless

Is known to be the wisest woman in Europe,

With a wicked pack of cards. Here, said she,

Is your card, the drowned Phoenician Sailor,

(Those are pearls that were his eyes. Look!)

Here is Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks,

The lady of situations.

Here is the man with three staves, and here the Wheel,

And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card,

Which is blank, is something he carries on his back,

Which I am forbidden to see. I do not find

The Hanged Man. Fear death by water.

I see crowds of people, walking round in a ring.

Thank you. If you see dear Mrs. Equitone,

Tell her I bring the horoscope myself:

One must be so careful these days.

Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours

With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying: “Stetson!

“You who were with me in the ships at Mylae!

“That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

“Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

“Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

“Oh keep the Dog far hence, that’s friend to men,

“Or with his nails he’ll dig it up again!

“You! hypocrite lecteur!—mon semblable,—mon frère!”

II. A Game of Chess

The Chair she sat in, like a burnished throne,

Glowed on the marble, where the glass

Held up by standards wrought with fruited vines

From which a golden Cupidon peeped out

(Another hid his eyes behind his wing)

Doubled the flames of sevenbranched candelabra

Reflecting light upon the table as

The glitter of her jewels rose to meet it,

From satin cases poured in rich profusion;

In vials of ivory and coloured glass

Unstoppered, lurked her strange synthetic perfumes,

Unguent, powdered, or liquid—troubled, confused

And drowned the sense in odours; stirred by the air

That freshened from the window, these ascended

In fattening the prolonged candle-flames,

Flung their smoke into the laquearia,

Stirring the pattern on the coffered ceiling.

Huge sea-wood fed with copper

Burned green and orange, framed by the coloured stone,

In which sad light a carvéd dolphin swam.

Above the antique mantel was displayed

As though a window gave upon the sylvan scene

The change of Philomel, by the barbarous king

So rudely forced; yet there the nightingale

Filled all the desert with inviolable voice

And still she cried, and still the world pursues,

“Jug Jug” to dirty ears.

And other withered stumps of time

Were told upon the walls; staring forms

Leaned out, leaning, hushing the room enclosed.

Footsteps shuffled on the stair.

Under the firelight, under the brush, her hair

Spread out in fiery points

Glowed into words, then would be savagely still.

“My nerves are bad tonight. Yes, bad. Stay with me.

“Speak to me. Why do you never speak. Speak.

“What are you thinking of? What thinking? What?

“I never know what you are thinking. Think.”

I think we are in rats’ alley

Where the dead men lost their bones.

“What is that noise?”

The wind under the door.

“What is that noise now? What is the wind doing?”

Nothing again nothing.

“Do

“You know nothing? Do you see nothing? Do you remember

“Nothing?”

I remember

Those are pearls that were his eyes.

“Are you alive, or not? Is there nothing in your head?”

But

O O O O that Shakespeherian Rag—

It’s so elegant

So intelligent

“What shall I do now? What shall I do?”

“I shall rush out as I am, and walk the street

“With my hair down, so. What shall we do tomorrow?

“What shall we ever do?”

The hot water at ten.

And if it rains, a closed car at four.

And we shall play a game of chess,

Pressing lidless eyes and waiting for a knock upon the door.

When Lil’s husband got demobbed, I said—

I didn’t mince my words, I said to her myself,

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

Now Albert’s coming back, make yourself a bit smart.

He’ll want to know what you done with that money he gave you

To get yourself some teeth. He did, I was there.

You have them all out, Lil, and get a nice set,

He said, I swear, I can’t bear to look at you.

And no more can’t I, I said, and think of poor Albert,

He’s been in the army four years, he wants a good time,

And if you don’t give it him, there’s others will, I said.

Oh is there, she said. Something o’ that, I said.

Then I’ll know who to thank, she said, and give me a straight look.

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

If you don’t like it you can get on with it, I said.

Others can pick and choose if you can’t.

But if Albert makes off, it won’t be for lack of telling.

You ought to be ashamed, I said, to look so antique.

(And her only thirty-one.)

I can’t help it, she said, pulling a long face,

It’s them pills I took, to bring it off, she said.

(She’s had five already, and nearly died of young George.)

The chemist said it would be all right, but I’ve never been the same.

You are a proper fool, I said.

Well, if Albert won’t leave you alone, there it is, I said,

What you get married for if you don’t want children?

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

Well, that Sunday Albert was home, they had a hot gammon,

And they asked me in to dinner, to get the beauty of it hot—

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

Goonight Bill. Goonight Lou. Goonight May. Goonight.

Ta ta. Goonight. Goonight.

Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night.

III. The Fire Sermon

The river’s tent is broken: the last fingers of leaf

Clutch and sink into the wet bank. The wind

Crosses the brown land, unheard. The nymphs are departed.

Sweet Thames, run softly, till I end my song.

The river bears no empty bottles, sandwich papers,

Silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes, cigarette ends

Or other testimony of summer nights. The nymphs are departed.

And their friends, the loitering heirs of city directors;

Departed, have left no addresses.

By the waters of Leman I sat down and wept . . .

Sweet Thames, run softly till I end my song,

Sweet Thames, run softly, for I speak not loud or long.

But at my back in a cold blast I hear

The rattle of the bones, and chuckle spread from ear to ear.

A rat crept softly through the vegetation

Dragging its slimy belly on the bank

While I was fishing in the dull canal

On a winter evening round behind the gashouse

Musing upon the king my brother’s wreck

And on the king my father’s death before him.

White bodies naked on the low damp ground

And bones cast in a little low dry garret,

Rattled by the rat’s foot only, year to year.

But at my back from time to time I hear

The sound of horns and motors, which shall bring

Sweeney to Mrs. Porter in the spring.

O the moon shone bright on Mrs. Porter

And on her daughter

They wash their feet in soda water

Et O ces voix d’enfants, chantant dans la coupole!

Twit twit twit

Jug jug jug jug jug jug

So rudely forc’d.

Tereu

Unreal City

Under the brown fog of a winter noon

Mr. Eugenides, the Smyrna merchant

Unshaven, with a pocket full of currants

C.i.f. London: documents at sight,

Asked me in demotic French

To luncheon at the Cannon Street Hotel

Followed by a weekend at the Metropole.

At the violet hour, when the eyes and back

Turn upward from the desk, when the human engine waits

Like a taxi throbbing waiting,

I Tiresias, though blind, throbbing between two lives,

Old man with wrinkled female breasts, can see

At the violet hour, the evening hour that strives

Homeward, and brings the sailor home from sea,

The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights

Her stove, and lays out food in tins.

Out of the window perilously spread

Her drying combinations touched by the sun’s last rays,

On the divan are piled (at night her bed)

Stockings, slippers, camisoles, and stays.

I Tiresias, old man with wrinkled dugs

Perceived the scene, and foretold the rest—

I too awaited the expected guest.

He, the young man carbuncular, arrives,

A small house agent’s clerk, with one bold stare,

One of the low on whom assurance sits

As a silk hat on a Bradford millionaire.

The time is now propitious, as he guesses,

The meal is ended, she is bored and tired,

Endeavours to engage her in caresses

Which still are unreproved, if undesired.

Flushed and decided, he assaults at once;

Exploring hands encounter no defence;

His vanity requires no response,

And makes a welcome of indifference.

(And I Tiresias have foresuffered all

Enacted on this same divan or bed;

I who have sat by Thebes below the wall

And walked among the lowest of the dead.)

Bestows one final patronising kiss,

And gropes his way, finding the stairs unlit . . .

She turns and looks a moment in the glass,

Hardly aware of her departed lover;

Her brain allows one half-formed thought to pass:

“Well now that’s done: and I’m glad it’s over.”

When lovely woman stoops to folly and

Paces about her room again, alone,

She smoothes her hair with automatic hand,

And puts a record on the gramophone.

“This music crept by me upon the waters”

And along the Strand, up Queen Victoria Street.

O City city, I can sometimes hear

Beside a public bar in Lower Thames Street,

The pleasant whining of a mandoline

And a clatter and a chatter from within

Where fishmen lounge at noon: where the walls

Of Magnus Martyr hold

Inexplicable splendour of Ionian white and gold.

The river sweats

Oil and tar

The barges drift

With the turning tide

Red sails

Wide

To leeward, swing on the heavy spar.

The barges wash

Drifting logs

Down Greenwich reach

Past the Isle of Dogs.

Weialala leia

Wallala leialala

Elizabeth and Leicester

Beating oars

The stern was formed

A gilded shell

Red and gold

The brisk swell

Rippled both shores

Southwest wind

Carried down stream

The peal of bells

White towers

Weialala leia

Wallala leialala

“Trams and dusty trees.

Highbury bore me. Richmond and Kew

Undid me. By Richmond I raised my knees

Supine on the floor of a narrow canoe.”

“My feet are at Moorgate, and my heart

Under my feet. After the event

He wept. He promised a ‘new start.’

I made no comment. What should I resent?”

“On Margate Sands.

I can connect

Nothing with nothing.

The broken fingernails of dirty hands.

My people humble people who expect

Nothing.”

la la

To Carthage then I came

Burning burning burning burning

O Lord Thou pluckest me out

O Lord Thou pluckest

burning

IV. Death by Water

Phlebas the Phoenician, a fortnight dead,

Forgot the cry of gulls, and the deep sea swell

And the profit and loss.

A current under sea

Picked his bones in whispers. As he rose and fell

He passed the stages of his age and youth

Entering the whirlpool.

Gentile or Jew

O you who turn the wheel and look to windward,

Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you.

V. What the Thunder Said

After the torchlight red on sweaty faces

After the frosty silence in the gardens

After the agony in stony places

The shouting and the crying

Prison and palace and reverberation

Of thunder of spring over distant mountains

He who was living is now dead

We who were living are now dying

With a little patience

Here is no water but only rock

Rock and no water and the sandy road

The road winding above among the mountains

Which are mountains of rock without water

If there were water we should stop and drink

Amongst the rock one cannot stop or think

Sweat is dry and feet are in the sand

If there were only water amongst the rock

Dead mountain mouth of carious teeth that cannot spit

Here one can neither stand nor lie nor sit

There is not even silence in the mountains

But dry sterile thunder without rain

There is not even solitude in the mountains

But red sullen faces sneer and snarl

From doors of mudcracked houses

If there were water

And no rock

If there were rock

And also water

And water

A spring

A pool among the rock

If there were the sound of water only

Not the cicada

And dry grass singing

But sound of water over a rock

Where the hermit-thrush sings in the pine trees

Drip drop drip drop drop drop drop

But there is no water

Who is the third who walks always beside you?

When I count, there are only you and I together

But when I look ahead up the white road

There is always another one walking beside you

Gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded

I do not know whether a man or a woman

—But who is that on the other side of you?

What is that sound high in the air

Murmur of maternal lamentation

Who are those hooded hordes swarming

Over endless plains, stumbling in cracked earth

Ringed by the flat horizon only

What is the city over the mountains

Cracks and reforms and bursts in the violet air

Falling towers

Jerusalem Athens Alexandria

Vienna London

Unreal

A woman drew her long black hair out tight

And fiddled whisper music on those strings

And bats with baby faces in the violet light

Whistled, and beat their wings

And crawled head downward down a blackened wall

And upside down in air were towers

Tolling reminiscent bells, that kept the hours

And voices singing out of empty cisterns and exhausted wells.

In this decayed hole among the mountains

In the faint moonlight, the grass is singing

Over the tumbled graves, about the chapel

There is the empty chapel, only the wind’s home.

It has no windows, and the door swings,

Dry bones can harm no one.

Only a cock stood on the rooftree

Co co rico co co rico

In a flash of lightning. Then a damp gust

Bringing rain

Ganga was sunken, and the limp leaves

Waited for rain, while the black clouds

Gathered far distant, over Himavant.

The jungle crouched, humped in silence.

Then spoke the thunder

DA

Datta: what have we given?

My friend, blood shaking my heart

The awful daring of a moment’s surrender

Which an age of prudence can never retract

By this, and this only, we have existed

Which is not to be found in our obituaries

Or in memories draped by the beneficent spider

Or under seals broken by the lean solicitor

In our empty rooms

DA

Dayadhvam: I have heard the key

Turn in the door once and turn once only

We think of the key, each in his prison

Thinking of the key, each confirms a prison

Only at nightfall, aethereal rumours

Revive for a moment a broken Coriolanus

DA

Damyata: The boat responded

Gaily, to the hand expert with sail and oar

The sea was calm, your heart would have responded

Gaily, when invited, beating obedient

To controlling hands

I sat upon the shore

Fishing, with the arid plain behind me

Shall I at least set my lands in order?

London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down

Poi s’ascose nel foco che gli affina

Quando fiam uti chelidon—O swallow swallow

Le Prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolie

These fragments I have shored against my ruins

Why then Ile fit you. Hieronymo’s mad againe.

Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata.

Shantih shantih shantih

Shantih means peace in Hindi

BY T. S. ELIOT

FOR EZRA POUND

IL MIGLIOR FABBRO

I. The Burial of the Dead

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

Summer surprised us, coming over the Starnbergersee

With a shower of rain; we stopped in the colonnade,

And went on in sunlight, into the Hofgarten,

And drank coffee, and talked for an hour.

Bin gar keine Russin, stamm’ aus Litauen, echt deutsch.

And when we were children, staying at the arch-duke’s,

My cousin’s, he took me out on a sled,

And I was frightened. He said, Marie,

Marie, hold on tight. And down we went.

In the mountains, there you feel free.

I read, much of the night, and go south in the winter.

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,

And the dry stone no sound of water. Only

There is shadow under this red rock,

(Come in under the shadow of this red rock),

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

Frisch weht der Wind

Der Heimat zu

Mein Irisch Kind,

Wo weilest du?

“You gave me hyacinths first a year ago;

“They called me the hyacinth girl.”

—Yet when we came back, late, from the Hyacinth garden,

Your arms full, and your hair wet, I could not

Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither

Living nor dead, and I knew nothing,

Looking into the heart of light, the silence.

Oed’ und leer das Meer.

Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante,

Had a bad cold, nevertheless

Is known to be the wisest woman in Europe,

With a wicked pack of cards. Here, said she,

Is your card, the drowned Phoenician Sailor,

(Those are pearls that were his eyes. Look!)

Here is Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks,

The lady of situations.

Here is the man with three staves, and here the Wheel,

And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card,

Which is blank, is something he carries on his back,

Which I am forbidden to see. I do not find

The Hanged Man. Fear death by water.

I see crowds of people, walking round in a ring.

Thank you. If you see dear Mrs. Equitone,

Tell her I bring the horoscope myself:

One must be so careful these days.

Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours

With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying: “Stetson!

“You who were with me in the ships at Mylae!

“That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

“Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

“Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

“Oh keep the Dog far hence, that’s friend to men,

“Or with his nails he’ll dig it up again!

“You! hypocrite lecteur!—mon semblable,—mon frère!”

II. A Game of Chess

The Chair she sat in, like a burnished throne,

Glowed on the marble, where the glass

Held up by standards wrought with fruited vines

From which a golden Cupidon peeped out

(Another hid his eyes behind his wing)

Doubled the flames of sevenbranched candelabra

Reflecting light upon the table as

The glitter of her jewels rose to meet it,

From satin cases poured in rich profusion;

In vials of ivory and coloured glass

Unstoppered, lurked her strange synthetic perfumes,

Unguent, powdered, or liquid—troubled, confused

And drowned the sense in odours; stirred by the air

That freshened from the window, these ascended

In fattening the prolonged candle-flames,

Flung their smoke into the laquearia,

Stirring the pattern on the coffered ceiling.

Huge sea-wood fed with copper

Burned green and orange, framed by the coloured stone,

In which sad light a carvéd dolphin swam.

Above the antique mantel was displayed

As though a window gave upon the sylvan scene

The change of Philomel, by the barbarous king

So rudely forced; yet there the nightingale

Filled all the desert with inviolable voice

And still she cried, and still the world pursues,

“Jug Jug” to dirty ears.

And other withered stumps of time

Were told upon the walls; staring forms

Leaned out, leaning, hushing the room enclosed.

Footsteps shuffled on the stair.

Under the firelight, under the brush, her hair

Spread out in fiery points

Glowed into words, then would be savagely still.

“My nerves are bad tonight. Yes, bad. Stay with me.

“Speak to me. Why do you never speak. Speak.

“What are you thinking of? What thinking? What?

“I never know what you are thinking. Think.”

I think we are in rats’ alley

Where the dead men lost their bones.

“What is that noise?”

The wind under the door.

“What is that noise now? What is the wind doing?”

Nothing again nothing.

“Do

“You know nothing? Do you see nothing? Do you remember

“Nothing?”

I remember

Those are pearls that were his eyes.

“Are you alive, or not? Is there nothing in your head?”

But

O O O O that Shakespeherian Rag—

It’s so elegant

So intelligent

“What shall I do now? What shall I do?”

“I shall rush out as I am, and walk the street

“With my hair down, so. What shall we do tomorrow?

“What shall we ever do?”

The hot water at ten.

And if it rains, a closed car at four.

And we shall play a game of chess,

Pressing lidless eyes and waiting for a knock upon the door.

When Lil’s husband got demobbed, I said—

I didn’t mince my words, I said to her myself,

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

Now Albert’s coming back, make yourself a bit smart.

He’ll want to know what you done with that money he gave you

To get yourself some teeth. He did, I was there.

You have them all out, Lil, and get a nice set,

He said, I swear, I can’t bear to look at you.

And no more can’t I, I said, and think of poor Albert,

He’s been in the army four years, he wants a good time,

And if you don’t give it him, there’s others will, I said.

Oh is there, she said. Something o’ that, I said.

Then I’ll know who to thank, she said, and give me a straight look.

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

If you don’t like it you can get on with it, I said.

Others can pick and choose if you can’t.

But if Albert makes off, it won’t be for lack of telling.

You ought to be ashamed, I said, to look so antique.

(And her only thirty-one.)

I can’t help it, she said, pulling a long face,

It’s them pills I took, to bring it off, she said.

(She’s had five already, and nearly died of young George.)

The chemist said it would be all right, but I’ve never been the same.

You are a proper fool, I said.

Well, if Albert won’t leave you alone, there it is, I said,

What you get married for if you don’t want children?

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

Well, that Sunday Albert was home, they had a hot gammon,

And they asked me in to dinner, to get the beauty of it hot—

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

Goonight Bill. Goonight Lou. Goonight May. Goonight.

Ta ta. Goonight. Goonight.

Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night.

III. The Fire Sermon

The river’s tent is broken: the last fingers of leaf

Clutch and sink into the wet bank. The wind

Crosses the brown land, unheard. The nymphs are departed.

Sweet Thames, run softly, till I end my song.

The river bears no empty bottles, sandwich papers,

Silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes, cigarette ends

Or other testimony of summer nights. The nymphs are departed.

And their friends, the loitering heirs of city directors;

Departed, have left no addresses.

By the waters of Leman I sat down and wept . . .

Sweet Thames, run softly till I end my song,

Sweet Thames, run softly, for I speak not loud or long.

But at my back in a cold blast I hear

The rattle of the bones, and chuckle spread from ear to ear.

A rat crept softly through the vegetation

Dragging its slimy belly on the bank

While I was fishing in the dull canal

On a winter evening round behind the gashouse

Musing upon the king my brother’s wreck

And on the king my father’s death before him.

White bodies naked on the low damp ground

And bones cast in a little low dry garret,

Rattled by the rat’s foot only, year to year.

But at my back from time to time I hear

The sound of horns and motors, which shall bring

Sweeney to Mrs. Porter in the spring.

O the moon shone bright on Mrs. Porter

And on her daughter

They wash their feet in soda water

Et O ces voix d’enfants, chantant dans la coupole!

Twit twit twit

Jug jug jug jug jug jug

So rudely forc’d.

Tereu

Unreal City

Under the brown fog of a winter noon

Mr. Eugenides, the Smyrna merchant

Unshaven, with a pocket full of currants

C.i.f. London: documents at sight,

Asked me in demotic French

To luncheon at the Cannon Street Hotel

Followed by a weekend at the Metropole.

At the violet hour, when the eyes and back

Turn upward from the desk, when the human engine waits

Like a taxi throbbing waiting,

I Tiresias, though blind, throbbing between two lives,

Old man with wrinkled female breasts, can see

At the violet hour, the evening hour that strives

Homeward, and brings the sailor home from sea,

The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights

Her stove, and lays out food in tins.

Out of the window perilously spread

Her drying combinations touched by the sun’s last rays,

On the divan are piled (at night her bed)

Stockings, slippers, camisoles, and stays.

I Tiresias, old man with wrinkled dugs

Perceived the scene, and foretold the rest—

I too awaited the expected guest.

He, the young man carbuncular, arrives,

A small house agent’s clerk, with one bold stare,

One of the low on whom assurance sits

As a silk hat on a Bradford millionaire.

The time is now propitious, as he guesses,

The meal is ended, she is bored and tired,

Endeavours to engage her in caresses

Which still are unreproved, if undesired.

Flushed and decided, he assaults at once;

Exploring hands encounter no defence;

His vanity requires no response,

And makes a welcome of indifference.

(And I Tiresias have foresuffered all

Enacted on this same divan or bed;

I who have sat by Thebes below the wall

And walked among the lowest of the dead.)

Bestows one final patronising kiss,

And gropes his way, finding the stairs unlit . . .

She turns and looks a moment in the glass,

Hardly aware of her departed lover;

Her brain allows one half-formed thought to pass:

“Well now that’s done: and I’m glad it’s over.”

When lovely woman stoops to folly and

Paces about her room again, alone,

She smoothes her hair with automatic hand,

And puts a record on the gramophone.

“This music crept by me upon the waters”

And along the Strand, up Queen Victoria Street.

O City city, I can sometimes hear

Beside a public bar in Lower Thames Street,

The pleasant whining of a mandoline

And a clatter and a chatter from within

Where fishmen lounge at noon: where the walls

Of Magnus Martyr hold

Inexplicable splendour of Ionian white and gold.

The river sweats

Oil and tar

The barges drift

With the turning tide

Red sails

Wide

To leeward, swing on the heavy spar.

The barges wash

Drifting logs

Down Greenwich reach

Past the Isle of Dogs.

Weialala leia

Wallala leialala

Elizabeth and Leicester

Beating oars

The stern was formed

A gilded shell

Red and gold

The brisk swell

Rippled both shores

Southwest wind

Carried down stream

The peal of bells

White towers

Weialala leia

Wallala leialala

“Trams and dusty trees.

Highbury bore me. Richmond and Kew

Undid me. By Richmond I raised my knees

Supine on the floor of a narrow canoe.”

“My feet are at Moorgate, and my heart

Under my feet. After the event

He wept. He promised a ‘new start.’

I made no comment. What should I resent?”

“On Margate Sands.

I can connect

Nothing with nothing.

The broken fingernails of dirty hands.

My people humble people who expect

Nothing.”

la la

To Carthage then I came

Burning burning burning burning

O Lord Thou pluckest me out

O Lord Thou pluckest

burning

IV. Death by Water

Phlebas the Phoenician, a fortnight dead,

Forgot the cry of gulls, and the deep sea swell

And the profit and loss.

A current under sea

Picked his bones in whispers. As he rose and fell

He passed the stages of his age and youth

Entering the whirlpool.

Gentile or Jew

O you who turn the wheel and look to windward,

Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you.

V. What the Thunder Said

After the torchlight red on sweaty faces

After the frosty silence in the gardens

After the agony in stony places

The shouting and the crying

Prison and palace and reverberation

Of thunder of spring over distant mountains

He who was living is now dead

We who were living are now dying

With a little patience

Here is no water but only rock

Rock and no water and the sandy road

The road winding above among the mountains

Which are mountains of rock without water

If there were water we should stop and drink

Amongst the rock one cannot stop or think

Sweat is dry and feet are in the sand

If there were only water amongst the rock

Dead mountain mouth of carious teeth that cannot spit

Here one can neither stand nor lie nor sit

There is not even silence in the mountains

But dry sterile thunder without rain

There is not even solitude in the mountains

But red sullen faces sneer and snarl

From doors of mudcracked houses

If there were water

And no rock

If there were rock

And also water

And water

A spring

A pool among the rock

If there were the sound of water only

Not the cicada

And dry grass singing

But sound of water over a rock

Where the hermit-thrush sings in the pine trees

Drip drop drip drop drop drop drop

But there is no water

Who is the third who walks always beside you?

When I count, there are only you and I together

But when I look ahead up the white road

There is always another one walking beside you

Gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded

I do not know whether a man or a woman

—But who is that on the other side of you?

What is that sound high in the air

Murmur of maternal lamentation

Who are those hooded hordes swarming

Over endless plains, stumbling in cracked earth

Ringed by the flat horizon only

What is the city over the mountains

Cracks and reforms and bursts in the violet air

Falling towers

Jerusalem Athens Alexandria

Vienna London

Unreal

A woman drew her long black hair out tight

And fiddled whisper music on those strings

And bats with baby faces in the violet light

Whistled, and beat their wings

And crawled head downward down a blackened wall

And upside down in air were towers

Tolling reminiscent bells, that kept the hours

And voices singing out of empty cisterns and exhausted wells.

In this decayed hole among the mountains

In the faint moonlight, the grass is singing

Over the tumbled graves, about the chapel

There is the empty chapel, only the wind’s home.

It has no windows, and the door swings,

Dry bones can harm no one.

Only a cock stood on the rooftree

Co co rico co co rico

In a flash of lightning. Then a damp gust

Bringing rain

Ganga was sunken, and the limp leaves

Waited for rain, while the black clouds

Gathered far distant, over Himavant.

The jungle crouched, humped in silence.

Then spoke the thunder

DA

Datta: what have we given?

My friend, blood shaking my heart

The awful daring of a moment’s surrender

Which an age of prudence can never retract

By this, and this only, we have existed

Which is not to be found in our obituaries

Or in memories draped by the beneficent spider

Or under seals broken by the lean solicitor

In our empty rooms

DA

Dayadhvam: I have heard the key

Turn in the door once and turn once only

We think of the key, each in his prison

Thinking of the key, each confirms a prison

Only at nightfall, aethereal rumours

Revive for a moment a broken Coriolanus

DA

Damyata: The boat responded

Gaily, to the hand expert with sail and oar

The sea was calm, your heart would have responded

Gaily, when invited, beating obedient

To controlling hands

I sat upon the shore

Fishing, with the arid plain behind me

Shall I at least set my lands in order?

London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down

Poi s’ascose nel foco che gli affina

Quando fiam uti chelidon—O swallow swallow

Le Prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolie

These fragments I have shored against my ruins

Why then Ile fit you. Hieronymo’s mad againe.

Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata.

Shantih shantih shantih

Shantih means peace in Hindi