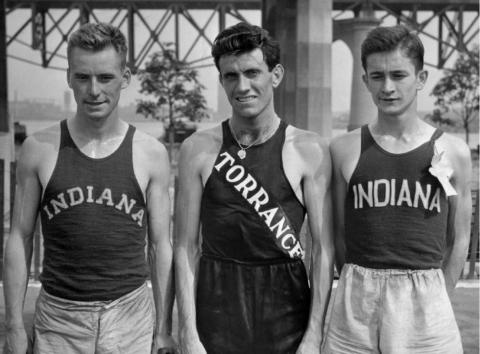

Zamperini in the 1936 Olympics

Louis Zamperini was born to Italian-immigrant parents - living in Olean, New York - on the 26th of January, 1917. He had an older brother (Pete) and two younger sisters (Sylvia and Virginia).

When the boys were still toddlers, they developed pneumonia. The family doctor recommended a move to California, so the Zamperinis - who still spoke Italian in their home - moved to Long Beach. Not long after, they settled in Torrance.

Often in trouble, Louie's focus changed when he was 15 years old. His brother suggested that athletics might be good for him, and Louie agreed.

Still in high school, he decided to run - as fast as he could - everywhere he could:

I had made up my mind to run everywhere. Instead of hitchiking to the beach four miles, I ran to the beach. I'd run from Redondo to Hermosa and back, and then run home at night. All summer long, that's what I did. So I piled up a lot of miles. But I had no idea how fast I could run. I had no idea what I was doing to my body.

Unwittingly, Zamperini was preparing himself for a great career as a top-notch athlete:

Then fall came around, and I was put in a two-mile cross-country run at UCLA. There were 101 runners out there from all over the state, and my first thought was: "I just hope I don't get last." When the race was over, I looked back and I had won it by a quarter of a mile. I thought I must have cut some corners, but they assured me that I ran the full course. I had no idea I was in such good shape because I had never timed myself. I just ran, ran, ran, and it paid off. So then I realized that I could be a runner - really a runner.

The former "Terror of Torrance" had new plans for himself and began to set aggressive goals:

I wanted to break the world's high school mile record in my senior year. Then I wanted to go to USC and break the NCAA mile record, and then make the 1940 Olympics in Tokyo. I got my high school world's record a year before, as a junior, which was a good thing for me, because my grades were not up to going to college...I had to make up my grades, so I went to summer school, became student body president, had to study even harder, and finally got my grades up to par. (Quoted passages from Louis Zamperini's Oral History.)

Unexpectedly, Louie had a chance to participate in the 1936 Summer Olympics which were scheduled for Berlin. One significant event had propelled him into the limelight. In May of 1934, he'd set a new record for the national interscholastic mile. His time - 4.21 and two-tenths - stood, unbroken, for eighteen years.

Arriving in Berlin, during the summer of 1936, Olympic athletes like Zamperini saw swastikas flying everywhere. The "Juden Verboten" signs - forbidding entry to Jewish people - were temporarily out of sight.

As head of state, Hitler opened the Games. Whenever he entered the stadium, to watch events, the crowds cheered for him. Once the audience even spelled out this greeting: Wir gehoeren Dir. Translated into English, that phrase means: "We belong to you."

Pleased with the performance of German athletes, and with the games in general, Hitler was nonetheless distressed by the numerous victories of Jesse Owens, a talented African-American who dominated his events. Winning four medals, Owens did not win-over a prejudiced Hitler who - according to Albert Speer - was upset about Owens' accomplishments:

Each of the German victories, and there were a surprising number of these, made [Adolf Hitler] happy, but he was highly annoyed by the series of triumphs by the marvelous colored American runner, Jesse Owens. (Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich.)

Louie did not compete against Jesse Owens. Instead, he ran the 5,000 meters - a long race that was not his forte - against a group of Finns who'd been winning the race for years.

Biding his time, he initially misjudged how fast his competitors would run. When he realized he needed to move more quickly, he kicked into high gear, finishing in 14:46.8 - the fastest 5,000-meter time for an American in 1936. He finished his last lap in 56 seconds.

Later, when he met Hitler, Louie was surprised that the German leader remembered him. "Ah," he said. "You're the boy with the fast finish."

Louie never thought he'd medal in the '36 Olympics. He believed the Tokyo games - set for 1940 - would be his path to an Olympic championship.

The Japanese government, however, had other plans. Invading China, and causing worldwide consternation with their warring ways, the government canceled the Olympics.

Louie, and other athletes hoping to compete, had a brief reprieve when the games were moved to Helsinki. Then ... Finland was caught-up in World War II - like other European nations - and the 1940 games were canceled altogether.

Disappointed that he could not actualize his potential in the Olympic arena, Zamp (as Louie was known by his friends) had a different job to do. After the Japanese empire bombed Pearl Harbor, America was drawn into World War II. Young men like Louie were joining the U.S. military.

In a twist of fate - although he hated to fly - Zamp would end up with a tough assignment. He would serve his country as a B-24 bombardier.

When the boys were still toddlers, they developed pneumonia. The family doctor recommended a move to California, so the Zamperinis - who still spoke Italian in their home - moved to Long Beach. Not long after, they settled in Torrance.

Often in trouble, Louie's focus changed when he was 15 years old. His brother suggested that athletics might be good for him, and Louie agreed.

Still in high school, he decided to run - as fast as he could - everywhere he could:

I had made up my mind to run everywhere. Instead of hitchiking to the beach four miles, I ran to the beach. I'd run from Redondo to Hermosa and back, and then run home at night. All summer long, that's what I did. So I piled up a lot of miles. But I had no idea how fast I could run. I had no idea what I was doing to my body.

Unwittingly, Zamperini was preparing himself for a great career as a top-notch athlete:

Then fall came around, and I was put in a two-mile cross-country run at UCLA. There were 101 runners out there from all over the state, and my first thought was: "I just hope I don't get last." When the race was over, I looked back and I had won it by a quarter of a mile. I thought I must have cut some corners, but they assured me that I ran the full course. I had no idea I was in such good shape because I had never timed myself. I just ran, ran, ran, and it paid off. So then I realized that I could be a runner - really a runner.

The former "Terror of Torrance" had new plans for himself and began to set aggressive goals:

I wanted to break the world's high school mile record in my senior year. Then I wanted to go to USC and break the NCAA mile record, and then make the 1940 Olympics in Tokyo. I got my high school world's record a year before, as a junior, which was a good thing for me, because my grades were not up to going to college...I had to make up my grades, so I went to summer school, became student body president, had to study even harder, and finally got my grades up to par. (Quoted passages from Louis Zamperini's Oral History.)

Unexpectedly, Louie had a chance to participate in the 1936 Summer Olympics which were scheduled for Berlin. One significant event had propelled him into the limelight. In May of 1934, he'd set a new record for the national interscholastic mile. His time - 4.21 and two-tenths - stood, unbroken, for eighteen years.

Arriving in Berlin, during the summer of 1936, Olympic athletes like Zamperini saw swastikas flying everywhere. The "Juden Verboten" signs - forbidding entry to Jewish people - were temporarily out of sight.

As head of state, Hitler opened the Games. Whenever he entered the stadium, to watch events, the crowds cheered for him. Once the audience even spelled out this greeting: Wir gehoeren Dir. Translated into English, that phrase means: "We belong to you."

Pleased with the performance of German athletes, and with the games in general, Hitler was nonetheless distressed by the numerous victories of Jesse Owens, a talented African-American who dominated his events. Winning four medals, Owens did not win-over a prejudiced Hitler who - according to Albert Speer - was upset about Owens' accomplishments:

Each of the German victories, and there were a surprising number of these, made [Adolf Hitler] happy, but he was highly annoyed by the series of triumphs by the marvelous colored American runner, Jesse Owens. (Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich.)

Louie did not compete against Jesse Owens. Instead, he ran the 5,000 meters - a long race that was not his forte - against a group of Finns who'd been winning the race for years.

Biding his time, he initially misjudged how fast his competitors would run. When he realized he needed to move more quickly, he kicked into high gear, finishing in 14:46.8 - the fastest 5,000-meter time for an American in 1936. He finished his last lap in 56 seconds.

Later, when he met Hitler, Louie was surprised that the German leader remembered him. "Ah," he said. "You're the boy with the fast finish."

Louie never thought he'd medal in the '36 Olympics. He believed the Tokyo games - set for 1940 - would be his path to an Olympic championship.

The Japanese government, however, had other plans. Invading China, and causing worldwide consternation with their warring ways, the government canceled the Olympics.

Louie, and other athletes hoping to compete, had a brief reprieve when the games were moved to Helsinki. Then ... Finland was caught-up in World War II - like other European nations - and the 1940 games were canceled altogether.

Disappointed that he could not actualize his potential in the Olympic arena, Zamp (as Louie was known by his friends) had a different job to do. After the Japanese empire bombed Pearl Harbor, America was drawn into World War II. Young men like Louie were joining the U.S. military.

In a twist of fate - although he hated to fly - Zamp would end up with a tough assignment. He would serve his country as a B-24 bombardier.